Pa., N.C. auto body shops’ RICO case against insurers dismissed; chance to file new suit by Dec. 15

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Legal | Repair Operations

Pennsylvania and North Carolina auto body shops’ class-action RICO case filed against the top auto insurers in the country has been denied, though the Florida judge in question will allow all the allegations to be re-argued.

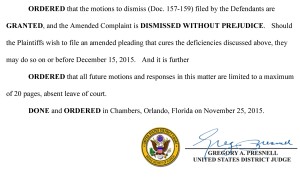

Setting a Dec. 15 deadline to amend Crawford’s Auto Center Inc. and K&M Collision LLC et al v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance et al Middle District of Florida Judge Gregory Presnell dismissed it without prejudice Wednesday.

Though the case wasn’t among the multistate fleet of collision repairer lawsuits following the lead of Florida’s failed A&E v. 21st Century case, it too was placed before Presnell given similarities in content. The cases all allege steering and collective actions by insurers to drive down shop labor rates.

In Crawford’s v. State Farm, the collision repairers accused the insurers of acting collectively in violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act rather than the Sherman Antitrust Act cited in most of the other cases. They also allege fraud and unjust enrichment.

Presnell wrote Wednesday that the lawsuit was far too broad as written now, calling the 157-page document “likely 100 pages longer than it ought to be.” He’s criticized the A&E family of cases on similar vagueness grounds.

“At the outset, the Court notes that the 157-page Amended Complaint is a prohibited ‘shotgun pleading,’ in that each of its counts realleges and reincorporates every preceding paragraph,” Presnell wrote Wednesday. “… And so on, down the line, with the fraud claim in Count VIII incorporating all of the RICO allegations asserted in the first seven counts (Amended Complaint at 159), and the unjust enrichment claim in Count IX incorporating all of those allegations plus the allegations from the fraud claim (Amended Complaint at 161). Without more, this warrants dismissal.”

Noting that this consideration was “far from the only serious flaw in the Amended Complaint,” he offered some other grounds — which could help by providing a roadmap for the Crawford attorneys.

The court does offer one ray of sunshine by calling a GEICO argument “premature” and not necessarily supported by the law.

Essentially, GEICO argued that it was its customers fault, not its own, that shops were being hurt.

“Specifically, GEICO argues that it contracts with its insureds (rather than repair shops) to pay for repairs, while it is the insureds that contract with the repair shops (and, presumably, underpay them),” Presnell wrote. “Thus, any injuries would have been inflicted on the Plaintiffs by GEICO’s insureds, not GEICO. However, this argument relies on facts outside the pleadings and is therefore premature.

“In addition, the Court cannot say that a defendant in GEICO’s position could not, as a matter of law, inflict an injury for purposes of Article III by defrauding or intimidating a service provider into providing its service to a third party more cheaply (with the resulting savings accruing to GEICO’s benefit).”

As another counterpoint to GEICO — and to offer our own little ray of sunshine — we offer this exchange from a lawsuit in Vermont. Learn more about that case, which is unrelated to any of the ones being heard by Presnell, from this April 2015 New England Automotive Report coverage.

Issues with judge’s ruling

Presnell’s ruling seems either overly dismissive or to not comprehend the shops’ argument.

Noting the shops’ allegation, “Defendant Insurers, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1951, extorted Plaintiffs and the proposed Classes through wrongful use of fear of economic loss, in that Plaintiffs and the members of the Classes would not be able to perform the insured repairs unless they accepted the suppressed compensation paid by Defendant Insurers,” Presnell calls it “nonsensical.”

“The Plaintiffs are arguing (1) that what they feared losing was not money but the ability to perform repairs on insured vehicles, and (2) that receiving compensation paid by insurance companies was not the benefit they received but rather the burden they shouldered to be able to continue performing repairs on insured vehicles,” he also wrote.

As to Point (1), Presnell seems not to understand that the ability to perform repairs on insured vehicles is what brings money to a shop.

If an insurer forces a customer to pay the difference, causing a policyholder who picked that shop (as is their right) to take their business elsewhere, or an insurer steers customers away from a shop which doesn’t agree to an artificial prevailing rate, that costs business, and therefore money.

As for 2, the loss of the difference in what the shops say they should have been paid and what they got would be the burden, not the work itself.

But then Presnell suddenly seems to understand the argument.

“In actuality, the Plaintiffs admit throughout the Amended Complaint that they accepted what they believed to be suppressed compensation because if they refused to work that cheaply, some other repair shop would get the work,” he writes.

Unfortunately, the law isn’t on the shops’ side, according to the judge: A potential benefit doesn’t count as a RICO extortion fear, he writes.

“Under the Hobbs Act, the victim must fear an actual loss, not merely the loss of a potential benefit,” Presnell wrote.

That could be a tougher nut to crack.

Also, the Hobbs Act requires the acquisition of property, according to Presnell. The shops’ argument that services count isn’t backed up by precedent within their lawsuit. A better citation might help here.

Just as it seemed as though Presnell understood the argument, he seems to forget it again with a gross oversimplification.

“Finally, even without these failures to satisfy the requirements of the Hobbs Act, the Plaintiffs’ own actions make it clear that there is no extortion here. Extortion involves a victim “agreeing” to do something because of a threat – e.g., “Pay me or I’ll burn down your business.” In the Amended Complaint, however, the Plaintiffs claim that they accepted reduced compensation for fear that the insurers would stop trying to offer them reduced compensation. “Give me a discount or I’ll leave you alone” is not extortion.”

“Give me a discount or your customers will leave you alone,” is what the insurers – who are middlemen in 75-90 percent of all auto repairs — are really saying, according to the shops.

Or, to use Presnell’s analogy, the real allegation seems to be “Pay me or I’ll keep customers from entering your business.”

And then, we have Presnell’s ludicrous conflation of an insurer to the actual customer.

“(T)here is nothing wrongful about a buyer threatening to take its business elsewhere unless the seller agrees to the buyer’s price,” he writes in one part of the dismissal.

Later, he seems to do the same, comparing an insurer’s participation in 70 percent of the market to the market itself.

“Moreover, the Plaintiffs allege that the entities that have established and pay the prevailing rate – the Defendant Insurers and the Conspirator Insurers – collectively make up about 70 percent of the automobile insurance market,”he writes. “One would expect to find that the rates paid by (at least) 70 percent of those in the market are, in fact, the prevailing rates. Accepting the allegations of the Amended Complaint in pertinent part as true, it appears that the alleged misrepresentations were not only not material, they were not misrepresentations.”

Only 50-60 percent of those repairs are DRP work, according to the shops, citing “industry reports.”

Essentially, Presnell is saying the customer is the middleman, and the insurer is the buyer. That’s like calling the guy holding your money in escrow for a transaction the buyer. Wonder if he feels the insurer is the buyer when he goes to the doctor?