Mitchell: Total-loss differences between original, final valuations could narrow with more build data

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Insurance | Market Trends

Though total-loss appraisals don’t change much between a first and second appraisal — just a couple hundred dollars — better build data up front might help carriers narrow that spread, a Mitchell analyst said.

Mitchell APD analytics senior manager Nate Raskin in the fourth-quarter Industry Trends Report examined disparities between what he described as two valuations of a totaled car: one done by an “original submitter,” one done by a “different submitter”

Raskin said Thursday that the term “original submitter” referred to whoever the first person to inspect and appraise the totaled vehicle. This typically would be an insurer field estimator, though it occasionally might be an auto body shop depending on workflows, Raskin said.

The “different submitter” was anybody else also issuing an opinion, such as a total loss adjuster, Raskin said.

When the original submitter issues the first valuation and then handles the revisions, the average total loss market value rises $65. When someone else does it, the valuation increases $249.

Raskin said some in the industry were operating under the assumption that “people are changing a lot of stuff” between valuations. But that wasn’t necessarily the case.

“A lot of it really had to do with equipment,” he said, calling build data, a comprehensive listing of all the features and options tied to that specific vehicle (and VIN), “critical.”

When the original submitter handles both valuations, the equipment amount only rises $2. When someone else does the final valuation, it soars $157.

Raskin wrote in the Industry Trends Report that the different submitter “may not have seen the vehicle (and may be more susceptible to inaccurate postinspection adjustments).” But the findings also suggest that the original estimator might have been tripped up by a lack of build data for the vehicles.

While he said Mitchell only had “about half” of the OEMs’ build data, some carriers aren’t even bothering to use that when preparing an estimate — and find themselves valuing cars less accurately than rivals who do.

Carriers who don’t use build data see about $238 per vehicle on equipment revisions, while those who use the existing build data only are off by $138, according to the Industry Trends Report.

“It made a pretty substantial difference,” Raskin said of build data.

Conditioning — evaluating what kind of shape the car was in before the loss — prompted an $18-$33 difference between the first and final valuation, depending on which submitter offered the second opinion. Checking on aftermarket (add-ons like lift kits, for example) or refurbished parts led to a $58-$68 increase between the first and last valuations.

Raskin said his total-loss study was more “introspective,” examining the aforementioned anecdotal hypothesis of extensive change during the total loss valuation life cycle. However, it seems like his findings still offer a lessons for carriers, and even repairers.

First, both industries might be able to collaborate on seeking build data access from the OEMs which apparently don’t provide it. Otherwise, they risk wasting the customer’s time tracking down all the information and unanticipated costs with supplements or the kind of total-loss revisions Raskin describes. There’s also the possibility that a repairer and insurer might miss and leave uncalibrated or inoperable an important safety feature like automatic braking.

Second, gathering as much data up-front as possible continues to make a difference. This has already been demonstrated on the repairable side of claims with disparities between photo estimates and in-person analysis, the persistence of supplements — 38.39 percent of Mitchell estimates in Q3 2016, up 3.68 percentage points — and the potential for customers to receive a more accurate delivery date if one waits for a teardown before providing an ETA.

Even with something like a total loss, both the customer and insurer seem as though they’d be better served by taking the time to research the vehicle. That way, the customer avoids being short-paid and the actuaries and bookkeepers can better anticipate money coming in and out and act accordingly.

“Market conditions may be driving higher total loss values, but achieving better accuracy is always within reach,” Raskin wrote in the Industry Trends Report. “If you haven’t done so already, consider activating build-sheet data. And if nothing else, use analytics to track revision activity—having a clear sense of who is changing what is a great prescription for managing accurate outcomes (and maintaining your professional sanity).”

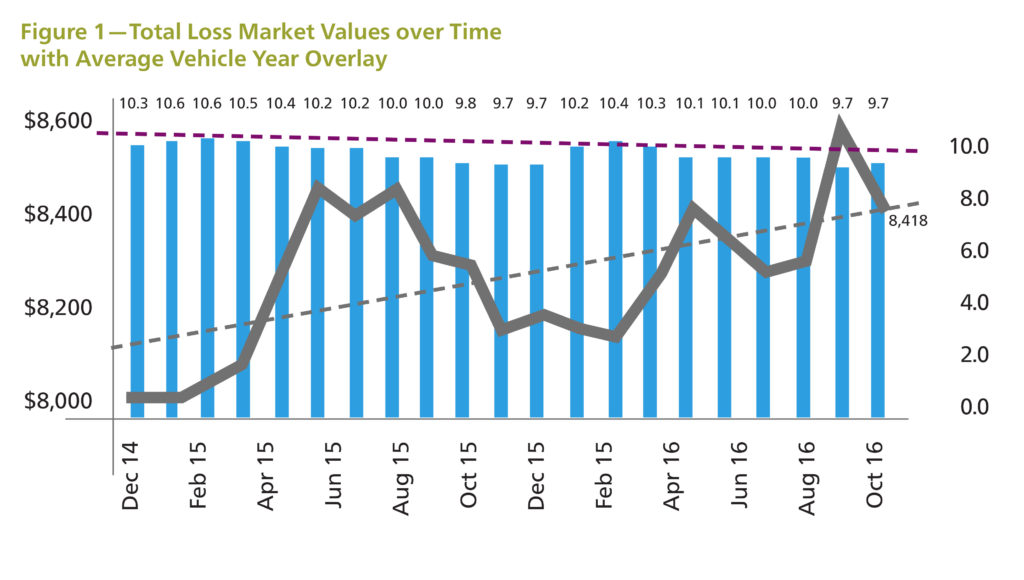

As for market conditions, Raskin observed in the Industry Trends Report that the year-to-date base value of total losses rose to $8,667 in the third quarter of 2016, up more than $200 from the $8,477 at the end of the year 2015.

“Along those lines, fully-baked market values are trending upward, showing an increase of about 1.5 percent compared to last September,” he wrote.

Totaled vehicles are slowly growing younger than in the past based on trends lines, coming in at 9.7 years in the third quarter compared to 9.8 a year ago. But Raskin pegged the price increase more to gains in used vehicle prices — up 5.1 percent wholesale in September, he wrote, citing ADESA Analytical Services.

More information:

Mitchell fourth-quarter Industry Trends Report

Mitchell, Dec. 12, 2016

Images:

This car might be an example of a total loss. (LizardinFla/iStock)

Mitchell’s fourth-quarter 2016 Industry Trends Report examined trend lines for total loss valuations and the age of totaled vehicles. (Provided by Mitchell)