Penn. Supreme Court: ‘Ill-will,’ ‘self-interest’ not necessary to win insurance bad-faith claim

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Legal

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Thursday ruled that a plaintiff doesn’t have to prove “ill will” or “self-interest” to successfully sue an insurer for violating the state’s “bad faith” statute.

The decision by Justice Max Baer is related to a health insurance claims denial, but it appears to have ramifications for the auto insurance space as well.

“Additionally, we hold that proof of an insurance company’s motive of self-interest or ill-will is not a prerequisite to prevailing in a bad faith claim under Section 8371, as argued by Appellant,” Baer wrote. “While such evidence is probative of the second Terletsky prong, we hold that evidence of the insurer’s knowledge or recklessness as to its lack of a reasonable basis in denying policy benefits is sufficient.”

The court agreed with the 1994 Superior Court opinion in Terletsky v. Prudential that a party suing an insurer must prove “(1) that the insurer did not have a reasonable basis for denying benefits under the policy and (2) that the insurer knew of

or recklessly disregarded its lack of a reasonable basis.”

Baer’s opinion was joined by five other justices, while Chief Justice Thomas Saylor and Justice David Wecht filed separate concurring opinions. Nobody dissented.

The case

According to the opinion in Rancosky v. Washington National, the case against Washington National parent company Conseco is a convoluted one but boils down to Conseco’s handling of LeAnn Rancosky’s supplemental cancer policy.

That policy contained a provision which allowed Rancosky to cease having to pay premiums if she were disabled from cancer. The premium-free coverage would kick in 90 days after her diagnosis.

Unfortunately, Rancosky became diagnosed with ovarian cancer Feb. 4, 2003. She quit working at her employer, the Postal Service, but had racked up so many vacation and sick days that she was able to remain on their payroll — and have her Conseco premiums deducted from those paychecks — until June 24, 2003, when she went on disability retirement.

According to the opinion:

Beginning in April 2003, Rancosky made several attempts to obtain waiver-of-premium status, claiming that she was unable to work and was thus “disabled” under her policy since her admission to the hospital in February of 2003. Upon Conseco’s request, on November 18, 2003, she submitted waiver-of-premium forms along with the required physician statement. Unbeknownst to Rancosky, however, the submitted physician’s statement inaccurately specified her date of disability as beginning on April 21, 2003, rather than on February 4, 2003. Believing that the premiums had been waived and that no further premiums were due on the policy because of her disability from cancer, Rancosky’s final premium payment came from her June 24, 2003, payroll-deducted premium. Thus, over the next two years, as Rancosky experienced several recurrences of her cancer, she continued to submit claims to Conseco.

For some undertermined reason, Conseco never received the physican’s statement until 2006. In 2005, it discovered “apparently for the first time” that Rancosky hadn’t been paying any premiums since 2003 and tried to quit paying for her care,” according to the opinion. She “submitted numerous claim forms, waiver-of-premium requests, and authorizations permitting Conseco to contact her physicians, employer, or anyone else who might have information regarding her disability start date.”

Conseco ultimately paid her bills for 2004 and 2005, but in 2006 told her it would not pay for a recurrence of her cancer, and the whole dance started again. She explained her situation, but Conseco would not hear any evidence other than the misdated doctor’s letter and didn’t bother to investigate beyond that — “Notwithstanding Rancosky’s eight separate authorizations permitting Conseco to contact her employer or any other person with information as to the actual start date of her disability,” according to the opinion.

She sued Conseco for breach of contract and bad faith for its apparent laziness. She won the breach of contract claim but lost the bad-faith claim; the trial court found Conseco “sloppy and even negligent” but ruled she didn’t prove its behavior was based on “some motive or self-interest or ill will.”

Rulings and ramifications

On appeal, the Superior Court agreed with Rancosky, finding that while self-interest or malice could be used to prove bad faith, it wasn’t the only form of bad faith claim, and “whether the insurer lacked a reasonable basis for denying benefits, is an objective inquiry and that the subjective intent of the insurer has no relevance thereunder,” according to the Supreme Court’s summary of the lower court’s views.

“The Superior Court concluded that if Conseco had conducted any meaningful investigation into the starting date of Rancosky’s cancer disability during its review of Rancosky’s reconsideration request, it would have discovered that she was unable to work due to her cancer diagnosis beginning on February 4, 2003, and that she made the required premium payments during the ninety-day waiting period of her cancer policy,” Baer’s opinion states.

The Superior Court kicked the case back to the trial court to redetermine if Conseco’s behavior was unreasonable enough to consistitute bad faith. Conseco appealed, but the Supreme Court ruled against the carrier, pointing to a history of Superior Court rulings interpreting bad faith in the same way and the Pennslyvania Legislature didn’t seem to demand a higher standard of proof for punitive bad faith lawsuits versus regular bad faith lawsuits.

“Given our conclusion that there is no basis to distinguish between punitive damages and other categories of damages under Section 8371, an ill-will level of culpability would limit recovery in any bad faith claim to the most egregious instances only where the plaintiff uncovers some sort of ‘smoking gun’ evidence indicating personal animus towards the insured,” the court wrote. “We do not believe that the General Assembly intended to create a standard so stringent that it would be highly unlikely that any plaintiff could prevail thereunder when it created the remedy for bad faith. Such a construction could functionally write bad faith under Section 8371 out of the law altogether.”

Aside from feeling that the trial court “should consider both prongs of the Terletsky test anew,” the Supreme Court agreed with the Superior Court.

“In summary, we hold that, to prevail in a bad faith insurance claim pursuant to Section 8371, a plaintiff must demonstrate, by clear and convincing evidence, (1) that the insurer did not have a reasonable basis for denying benefits under the policy and (2) that the insurer knew or recklessly disregarded its lack of a reasonable basis in denying the claim,” Baer wrote. “We further hold that proof of the insurer’s subjective motive of self-interest or ill-will, while perhaps probative of the second prong of the above test, is not a necessary prerequisite to succeeding in a bad faith claim. Rather, proof of the insurer’s knowledge or reckless disregard for its lack of reasonable basis in denying the claim is sufficient for demonstrating bad faith under the second prong.”

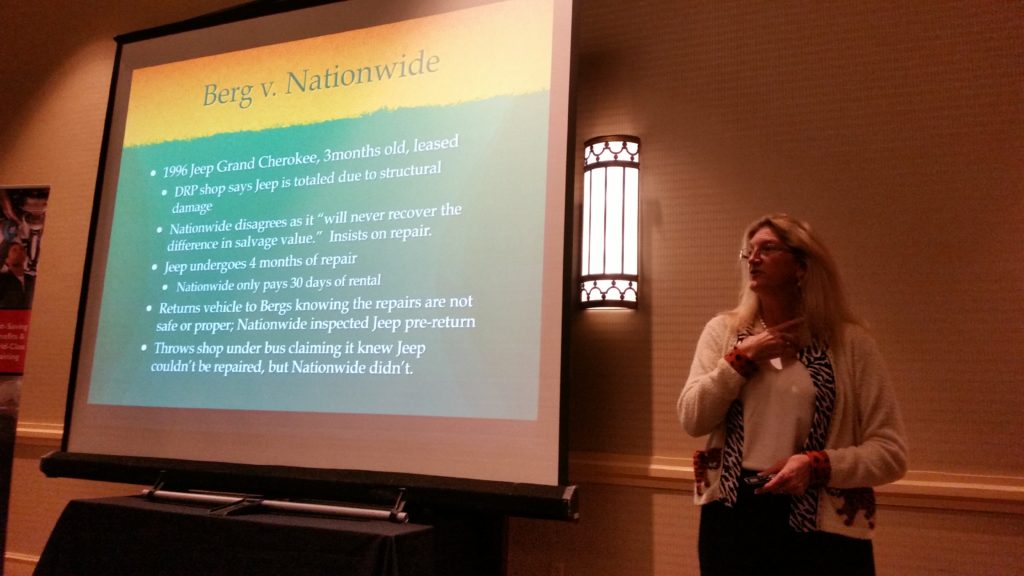

This case could have great impact for bad faith collision claims in Pennsylvania — perhaps most notably what a collision repair attorney has called the “absolutely horrendous” Berg v. Nationwide bad-faith case in that state. The case in May deadlocked the Pennsylvania Superior Court and will go before a different three-judge panel Oct. 10.

If an aggrieved policyholder don’t have to prove malice, merely an unreasonable insurance position and a refusal to reconsider that unreasonable position, it seems as though it’d be fairly easy for a Pennsylvania plaintiff to sue a carrier for the kind of behavior collision repairers nationally often report.

What else would you call an insurer refusing to pay for a procedure required by an OEM but unreasonable? Prong 1 has been met.

And what else would you call an insurer who relies on a “we don’t pay for that” or an arbitrary internal threshold instead of researching the easy-to-obtain manufacturer data and listening to the shop but one who “knew or recklessly disregarded its lack of a reasonable basis?” There would seem to be little difference between such an auto carrier and what the court described as Conseco’s refusal to at least check into what Rancosky had to say. Prong 2, check.

Images:

The Pennsylvania Judicial Center is shown. (ablokhin/iStock)

The 2017 Pennsylvania Supreme Court is shown. (Provided by Pennsylvania Supreme Court)

Collision repair attorney Erica Eversman highlighted the Berg v. Nationwide case during an Alliance of Automotive Service Providers-Pennsylvania event April 18, 2017, during CIC Week. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)