Wash. consumers pursue class-action suits against Allstate, Safeco subsidiary for total loss offers

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Legal | Market Trends

Two would-be class-action lawsuits in the Western District of Washington allege that insurers arbitrarily deflated the amount offered consumers for totaled cars using CCC software.

Neither Olberg and Palao-Vargas v. Allstate nor Lundquist v. First National name CCC as a defendant, suing solely their titular insurers on behalf of individual plaintiffs — and, should the court agree to the class, thousands of other first-party claimants across Washington who received certain total loss offers “from the earliest allowable time to the present,” according to both cases.

Both cases accuse their respective insurer of improper behavior related to settlement values based upon “comparable vehicles reduced by a ‘condition adjustment.'” Olberg v. Allstate also claims the carrier inappropriately treated at least one “gray-market vehicle” originally intended for Canada or other countries as comparable to a totaled American vehicle.

‘Condition adjustments’

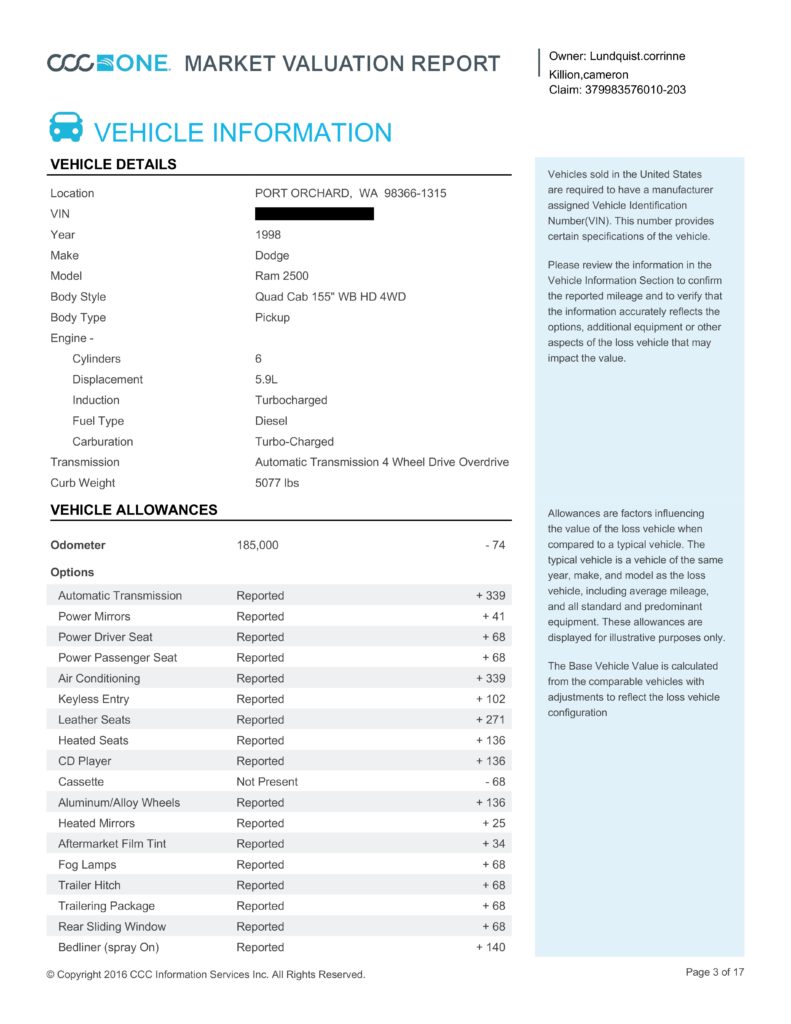

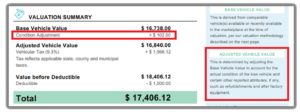

Cameron Lundquist sued Safeco subsidiary First National over its handling of a 1998 Dodge Ram 2500 Quad Cab totaled in 2017 for “$18.406.12 attributable to the value of the vehicle (minus deductible), citing its CCC valuation report.”

“First National instructs CCC as to what specific data to include in the report as the basis for the valuation, including whether to include condition adjustments to comparable vehicles,” the lawsuit states.

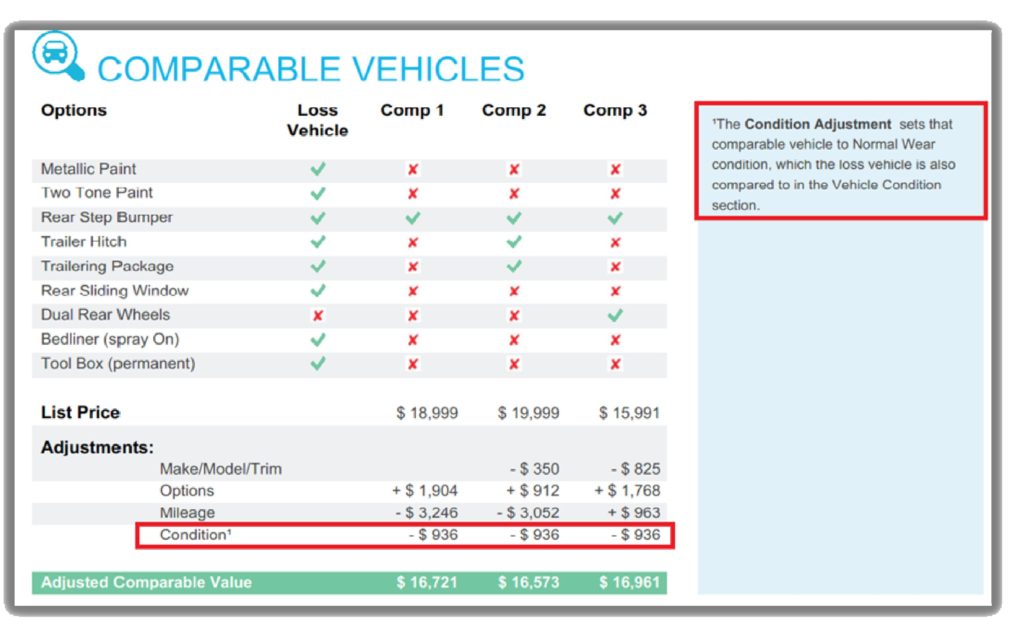

First National’s three comparable vehicles all had a $936 condition adjustment, a deflation the lawsuit claimed breached the contract and stiffed Lundquist out of $936 by not using the “actual cash value” of the trucks and by not itemizing or explaining the “condition adjustment.” The lawsuit also brings bad faith and deceptive trade pratices claims and seeks an injunction “permanently enjoining First National from basing its valuation and payment of the claim on values of comparable vehicles that have been artificially reduced by an arbitrary and unjustified ‘condition adjustment’ that is not itemized or explained.

The Olberg case makes similar claims regarding Allstate’s totaling of the two plaintiffs’ cars.

Jeff Olberg’s 2013 Ford Fusion Hybrid was totaled after a 2016 crash for $16.805.99, minus deductible, using a nine-vehicle valuation report that “applied a uniform condition adjustment of $775 to all nine of them without itemizing or explaining the basis of the adjustment as required by Washington law,” the lawsuit states. “The report reduced the amount of these comparable vehicles by exactly the same amount, regardless of any individual differences in the condition of the vehicles.”

Cecilia Ann Palao-Vargas’ 2011 Hyundai Sonata was totaled over a 2015 crash with a payout of $15,034.93, minus deductible. Again, Allstate used a CCC valuation report with nine similar vehicles, this time with a $684 “uniform condition adjustment” applied to all nine without itemization.

Washington law states, “Any additions or deductions from the actual cash value must be explained to the claimant and must be itemized showing specific dollar amounts.”

“The valuation reports reduce the estimated values of comparable vehicles, citing a ‘condition adjustment,’ but fail to itemize or explain the basis for these condition adjustments,” both lawsuits state. “These condition adjustments are arbitrary and unjustified. Indeed, even though each comparable vehicle has unique characteristics, the reports reduce the value of multiple comparable vehicles by the same amount, down to the last dollar, without any itemization or explanation for the amount. These blind and arbitrary reductions bear no relation to the actual fair market value of the comparable vehicles or the loss vehicle. The application of an arbitrary condition adjustment to reduce the value of comparable vehicles artificially reduces the valuation of the loss vehicle to benefit the insurer at the expense of the insured.”

All three plaintiffs alleged their respective insurer “fudges the numbers to shortchange vulnerable consumers, who have often lost their primary car” and need fair value back from the carrier to buy a new vehicle.

Asked if it wished to comment on the litigation, CCC said in a statement, “With respect to your article on the litigation, CCC can only add that its valuation product complies with applicable laws and believes the litigation is without merit.”

CCC declined to answer general product questions about CCC Market Valuation reports, including whether condition adjustments are calculated by CCC or customized to the insurer.

First National argued in a motion to dismiss that it had itemized and explained its deductions to Lundquist, even though Washington law says it didn’t have to do either, so there was no basis for the case. Its arguments are a bit letter of the law rather than the spirit:

“When settling a total loss vehicle claim using methods in subsections (1) through (3) of this section, the insurer must … Base all offers on itemized and verifiable dollar amounts for vehicles that are currently available, or were available within ninety days of the date of loss, using appropriate deductions or additions for options, mileage or condition when determining comparability,” Washington law states.

According to First National, all it needs to do under WAC 284-30-391(4)(b) is have itemized data available when it it makes its decision of how much to offer — the law here “does not impose any disclosure obligation.”

“Subsection (5)(d) does not apply to condition adjustments made to comparable vehicles,” the insurer wrote.

However, the law clearly states a carrier has to make this data available if asked for its valuation report, which must include:

In wonderful Bill Clinton “define is” factor, First National argues that “all” doesn’t really mean “all” the information it internally used to calculate the cash value, such as whatever deductions they made to the comparison vehicles.

Notably, that regulation specifically requires disclosure of “[a]ll information collected during the initial inspection assessing the condition, equipment, and mileage of the loss vehicle,” but no such requirement exists with respect to the condition of the comparable vehicles. Similarly, when using a computerized source to determine actual cash value, the regulation requires that “[a]ny weighting of identified [comparable] vehicles to arrive at an average must be documented and explained,” but no other category of information must be explained. The express mention of one item (e.g., disclosure of “all” information relating to the condition of the loss vehicle or explanation of weighting of comparable vehicles) implies the exclusion of others (e.g., disclosure of detailed information relating to the condition of the comparable vehicle or explanation of condition adjustments to the comparable vehicle). (apply the canon of expressio unius est exclusio alterius to interpretation of regulations).

However, we’d argue that all information the carrier used would indeed include its rationale for the particular numbers used.

Regardless, the carrier said it did indeed itemize and explain its adjustments.

“In any event, there can be no doubt that First National “itemized” every condition adjustment in the Valuation Report. In particular, First National itemized (and also explained) the $936 condition adjustment about which Plaintiff complains,” the carrier wrote pointing to this CCC page (emphasis First National’s):

“As the note in the right-hand column of that same page explains: “’The Condition Adjustment sets that comparable vehicle to Normal Wear condition, which the loss vehicle is also compared to in the Vehicle Condition section’ In other words, the condition adjustment to comparable vehicles was made in order to perform an apples-to-apples comparison between the loss vehicle, which is most commonly in Normal Wear, and the comparable vehicles, which are most commonly in Dealer Ready condition,” First National wrote. The carrier even credited Lundquist for having a dealer-ready dash and engine, kicking $102 back in his favor.

Just because Lundquist called the $936 reduction “arbitrary and unjustified” didn’t make it so, certainly not enough to let the litigation stand, First National said.

It’ll be interesting to see if the court agrees that assuming comparison vehicles are in better shape than a customer’s car is a fair assumption or sees First National as making too much of a leap.

“Because First National fully complied with WAC 284-30-391 – including, to the extent this Court finds such disclosure to be required, fully itemizing and explaining all condition adjustments – it is clear that the settlement offer to Plaintiff was based on the actual cash value of the loss vehicle,” First National wrote. “As such, there is no violation of the terms of the insurance policy (Count I); there is no breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing (Count II); there is no violation of the Washington Consumer Protection Act (Count III); and there is no basis for the declaratory or injunctive relief holding that Plaintiff requests (Count IV).”

‘Gray-market’

Olberg and Palao-Vargas are pursuing the same claims and injunction as Lundquist against Allstate. But they also seek a permanent injunction against Allstate from using “gray-market vehicles” to calculate how much to pay a total loss policyholder, as the carrier was accused of doing for Palao-Vargas.

“Allstate instructs CCC as to what specific data to include in the report as the basis for the valuation, including whether to include condition adjustments to comparable vehicles and whether to base the valuation on gray-market vehicles that are not comparable to the insured vehicle,” their lawsuit states.

The lawsuit argues that gray-market vehicles “are disfavored in the marketplace and generally less valuable” than cars made specifically for the United States. It states that gray-market cars can have lower prices because:

a. For a given year, make, and model, vehicles made for non-U.S. markets such as Canada have different safety and environmental specifications from vehicles made for the U.S. market and require modifications to comply with U.S. law.

b. Gray-market vehicles frequently lack a clear chain of title, increasing the risk that the vehicle has been stolen.

c. Gray-market vehicles are manufactured with an instrument panel and odometer that uses kilometers instead of miles, and the conversion from kilometers to miles creates a risk that the odometer has been manipulated.

d. The prices of gray-market vehicles are depressed by arbitrage. Because vehicle supply and demand varies from one country to the next, the cost of a gray-market vehicle is often lower than a vehicle of the same year, make, and model made for and sold in the United States.

A gray-market car isn’t the “comparable motor vehicle” required under Washington law, the lawsuit states.

“The use of gray-market vehicles to calculate the value of the loss vehicle artificially reduces the valuation of the loss vehicle to benefit the insurer at the expense of the insured,” the lawsuit states.

Allstate’s spokesmen don’t comment on pending litigation, and none of its counsel responded to an email request for comment Friday afternoon.

CCC also declined to answer general questions on whether the carrier or CCC makes the decision to include “gray-market” vehicles in a valuation result and why the IP would bother researching and providing such controversial data in the first place given the amount of truly U.S. vehicles for sale.

For example, in Palao-Vargas’ case, would it really have been that hard for Allstate to find nine U.S. 2011 Hyundai Sonatas within 150 miles from her house (the generally maximum distance acceptable under Washington law)? As of Friday, there’s a couple dozen of them for sale within a mere 100 miles of the district court’s ZIP Code, according to Autotrader.