WSJ: Harvey shouldn’t break bank of property-casualty insurers

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Market Trends

Collision repairers, customers and lawmakers should be skeptical of property and casualty insurer claims that Hurricane Harvey losses demand cutting insurers a break on expenses or regulation, based on a Sunday report by the Wall Street Journal.

According to the newspaper:

Harvey’s timing is good for insurers and insurance customers from one perspective: Personal and commercial insurers have record levels of capital, the money they have on hand that isn’t required to back obligations. With insurers’ overall strong capital position, Harvey is unlikely to cause extensive damage to the industry’s financial strength, though it could hurt quarterly earnings for those carriers with blocks of business in hard-hit areas.

The Wall Street Journal cited A.M. Best to declare State Farm, Allstate and Farmers the biggest homeowner’s insurers in the state. But flooding isn’t even a major concern for homeowner’s insurers as the federal National Flood Insurance Program typically covers it, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Auto insurers, however, are exposed to flooding through comprehensive policies added by about 75 percent of consumers with auto liability coverage, according to the Insurance Information Institute. The WSJ reported that State Farm, GEICO and Allstate are the top vehicle insurers in Texas.

Esurance observes that a car flooded by freshwater is an “obvious total loss” if the water reaches the dash, but a seawater-flooded vehicle only needs to reach the rocker panel before it’s an obvious total.

I-CAR teaches that fresh flood waters might have dirt and silt that can wear on moving parts. It also advises that establishing the height of the floodwater “is one of the key factors” in determining repairability. It warns that body damage can occur if the vehicle is pushed by the flooding. Total losses can occur once the water reaches the instrument panel, and length of submergence also can determine repairability.

“One of the biggest issues with flood-damaged vehicles is that it is difficult to write a complete and accurate estimate since it is almost impossible to determine how many systems were affected by floodwaters,” I-CAR writes in a module for teachers. “Once one vehicle system has been deemed repaired, multiple other systems often fail several months later. For this reason alone, flood vehicles are often written as total losses.”

It’d be interesting to hear from OEMs and I-CAR about repair and recalibration considerations for “low-hanging” and more easily flooded safety technology like park assist and blind-spot monitoring sensors and the rearview camera. (Are they weatherproofed enough to function after a flood, or would they be replace-only?)

While some major auto insurers might have a bad couple of quarters, the newspaper cited Insurance Information Institute data to report that the property and casualty insurance industry as a whole had $709 billion in surplus between January and March, “$1 in surplus for every 75 cents of net premiums.” So it’s fairly well protected for Harvey claims, according to the newspaper:

If you think about it, an insurer’s whole business model is based upon preparing for possible but randomly occurring events. It’d be absurd for an insurer writing business in the Gulf Coast not to have already priced the risk of a hurricane into their premiums or hedged it through some other financial means like the catastrophe bonds mentioned in the WSJ.

More information:

“Hurricane Harvey Unlikely to Damage Insurers’ Balance Sheets”

Wall Street Journal, Aug. 27, 2017

“Catastrophes: Insurance Issues”

Insurance Information Institute, November 2016

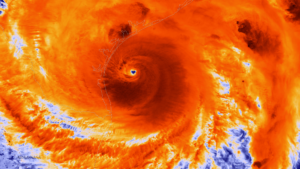

Featured image: The National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration and National Aeronautical and Space Administration’s NOAA/NASA Suomi NPP satellite shot this infrared image of Hurricane Harvey right before landfall on Friday, Aug. 25. The coastline has been overlain. (Provided by NOAA)