Fentanyl a growing concern in collision industry

By onBusiness Practices

One collision repair shop’s story about finding fentanyl in a recovered vehicle ignited conversation about the need for industry protocols during the Society of Collision Repair Specialists’ (SCRS) open board meeting in Richmond, Virginia.

Amber Alley, manager at Barsotti’s Body & Fender and SCRS’s immediate past president, said a stolen recovered vehicle was recently towed to her shop after being missing for more than 30 days.

“Immediately, the customer brought up concerns about someone living in the car,” Alley said.

There wasn’t any damage to the vehicle but it was disheveled, Alley said. She said the consumer voiced concerns about fentanyl and asked that the vehicle be tested.

“They went and talked with their insurance,” Alley said. “We tried to submit their concern to the insurer. It was denied. It was denied. It was denied. It was a standoff.”

The insurance company said the customer could pay for it, and they would consider reimbursement depending on the findings.

“We stored the car in our parking lot and basically roped it off and taped it up,” Alley said.

About a month after the vehicle was towed to the shop, the owner decided to pay for the testing, which cost more than $2,000, Alley said.

An abatement company conducted the testing. Dressed in hazardous waste suits, workers took six samples from different locations in the vehicle.

“Within a few days, we got the results back positive for fentanyl,” Alley said.

Alley said the tests detected fentanyl on the driver’s side seat, where a sticky substance was detected.

“I think about the tow truck driver who got in the car, and the police and the people who didn’t think ahead to protect themselves,” Alley said.

The vehicle was determined to be a total loss because the cost of abating the vehicle exceeded its value, she said.

Alley said it is important for collision repair shops to think about protocols to protect themselves and those who work in the industry.

Erin Solis, Square One Systems/Coyote Vision Group senior vice president, said she has spoken to several abatement groups on the topic and was told that about 90% of recovered vehicles they test come back positive for fentanyl.

“We need to document what we should do,” said Tim Ronak, AkzoNobel senior services consultant, during the meeting. “What’s the protocol for a theft recovery vehicle? How do we define that and help the industry understand the concerns? This is a huge hazard risk, not just for your employees, but for the auto wrecker locations. Anybody who gets in that car thinking, ‘I’ll put it in drive and roll it up onto the tow truck.’”

Solis suggested shops keep Narcan, an emergency treatment for opioid overdoses, on hand in case of exposure to fentanyl or other drugs.

Alley also suggested putting keys in plastic bags and for anyone touching vehicles to wear gloves.

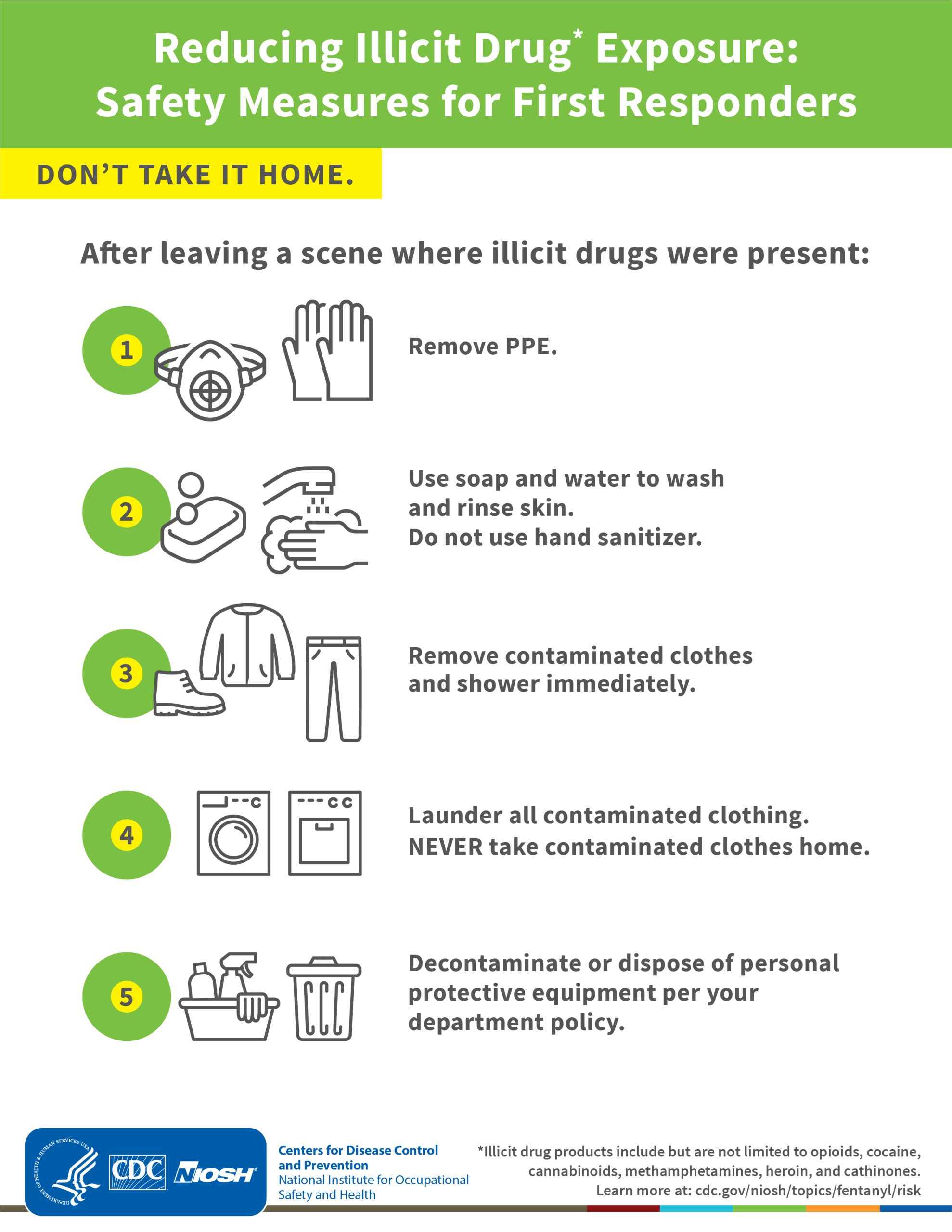

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide multiple resources and safety measures that first responders can use to reduce risk from fentanyl and other drugs.

The resources provide tips such as wearing personal protective equipment, including gloves, googles, and masks. It also suggests washing hands with soap and water after possible exposure.

The CDC also says not to touch the eyes, nose, or mouth following possible exposure and not to eat, drink, smoke, or use the bathroom. Anyone who comes in contact with fetanyl are also told not to use hand sanitizer as it does not remove illicit drugs and may increase exposure.

A HAZMAT crew or the DEA should be contacted if large amounts of suspected illicit drugs are visible, and only properly trained personnel in the appropriate PPE should perform field testing.

After leaving a scene where illicit drugs were present, those present should remove PPE and use soap and water to wash and rinse skin. Clothes should be removed, and the person should shower immediately. All clothes should be laundered before returning home, and all PPE should be disposed of per department policy.

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH) also provides training resources for any occupational exposure to illicit drugs.

NIH reports that 2-3 milligrams of fentanyl, comparable to 5-7 grains of salt, can induce respiratory depression, respiratory arrest, and death.

The routes of occupational exposure include inhalation of powders and aerosols; skin, eye, and mucous membrane absorption; incidental ingestion (hand to mouth); and accidental inoculation from sharp needles, according to NIH.

NIH notes that science organizations advise that incidental skin contact with dry products is not likely to cause overdoses. However, skin contact with liquid or gel can be highly toxic.

Occupational exposure case reports include first responders, crime lab analysts, and sniffer dogs, NIH says. However, it notes that all were administered naloxone (Narcan) and recovered.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has created exposure categories, according to NIH.

This includes:

-

- Minimal: Response to a situation where it is suspected that fentanyl may be present but no fentanyl products are visible Example: Response to a suspected fentanyl overdose or law enforcement operation where intelligence indicates fentanyl products are suspected but are not visible on scene.

- Moderate: Response to a situation where small amounts of fentanyl products are visible. Example: Response to a suspected fentanyl overdose where fentanyl products are suspected and small amounts are visible on scene.

- High: Response to a situation where liquid fentanyl or large amounts of fentanyl products are visible. Example: A fentanyl storage or distribution facility, fentanyl milling operation, or fentanyl production laboratory.

Images

Photo courtesy of Md Saiful Islam Khan/iStock