Damage from repairs, collisions could be undetectable by naked eye on aluminum, carbon fiber

By onMarket Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

Potential near-future growth in carbon fiber and aluminum use among OEMs could lead to shops having to be cognizant of the potential for damage at the microscopic level.

Ducker Worldwide predicted this summer that 25 percent of automotive doors and 71 percent of hoods would be aluminum by 2020.

While extrusions and cast parts are likely going to be replace-only, it is possible to repair aluminum panels, P&L Consultants co-owner Larry Montanez said on the June “Repair University Live.”

A fracture in cast aluminum creates microfractures, and welding that area generates “little tiny explosions” and more microfractures on the part, Montanez said on the Collision Hub show. (Subscribe to the $30 year-long series here.)

Even an aluminum sheet panel is prone to “microcracking,” and “ripping and tearing is very popular for it,” Montanez said. A shop might think it can repair such a torn part, but “it’s not going to last,” he said.

Heat from welding a damaged panel creates cracking on the outside of the panel, he said. Most outer panels are 0.9 mm thick, but if it’s torn or ripped, the damaged area dwindles to 0.6-0.7 mm, according to Montanez. When you try to weld and fill the void, the action causes heat cracking, thinning and work hardening, he said.

If you have a crack, rip or tear on the edge of a part like a fender, “it’s probably going to break again” following such a repair, Montanez said.

However, aluminum dent repair often requires a little heat, “Repair University” host Kristen Felder observed. (But low heat; aluminum melts at less than half the temperature steel does and is compromised long before that melting point.) When applying that heat, repairers need to think at the microscopic level, according to Montanez.

Never use propane torches to generate that heat, for it adds moisture to the expanded aluminum molecules, Montanez said. And never quick-cool the metal, or you’ll create microfractures.

“You gotta let it cool down itself,” he said. This could add time to the repair process, he noted.

Learn about lightweighting, joining during Repairer Driven Education

Learn about lightweighting and joining during SEMA with Ken Boylan of Chief at “Current and Future Technologies 2017 and Beyond”; Toby Chess of Kent Automotive at “Adhesive Joining in Modern Repairs”; Dave Gruskos of Reliable Automotive Equipment with “Get Attached to Following Procedures: A Comprehensive Guide to OEM Joining”; and a panel of OEM Collision Repair Technology Summit experts at “How Automotive Research is Driving Change.” The sessions are part of the Society of Collision Repair Specialists Repairer Driven Education Series Oct. 30-Nov. 3. Register here for individual classes or the series pass package deal.

If the paint on the part has cracked from too rapid a drop in temperature, it’s a good bet microcracking has also occurred, Montanez said. If you can see the paint failures, “what can’t you see?” he said.

He demonstrated an area which had been intentionally quick-cooled to generate microfractures in the factory paint job. “If the paint’s cracked like that … there’s a major, major, major issue,” he said.

He argued that every shop performing structural aluminum work should have a microfluxing dye kit to test for microfractures, particularly for welding. He gave the example of a Porsche Panamera 970, which has a piece of cast aluminum attached to extruded aluminum front rails. Porsche demands a shop dye-test the part for microfractures, which if present could compromise crashworthiness for a future collision, he said.

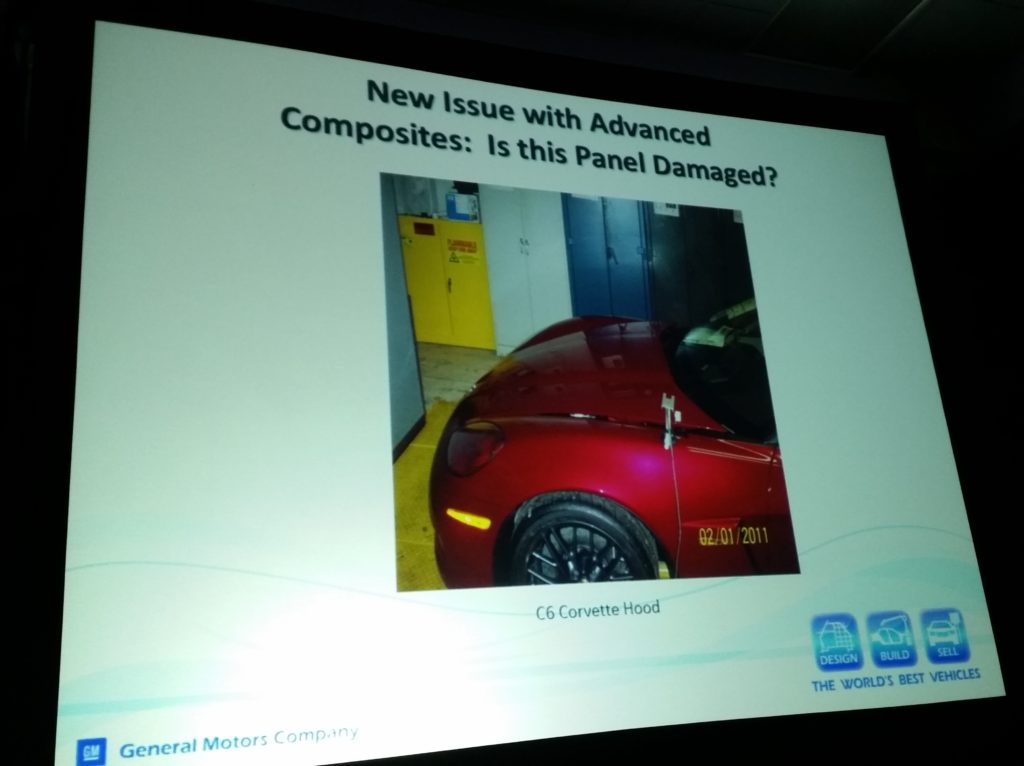

Carbon fiber — which might be farther into the future but sooner than we expect — also can be compromised at the microscopic level while appearing flawless to the naked eye, General Motors body structures advanced composites engineering group manager Mark Voss said last year during SEMA 2016.

In fact, unlike aluminum or steel panels, which deform when impacted with “nice, visible evidence,” a composite hood might not give any indication it’s been dented, according to Voss.

Voss said General Motors once hit a Corvette C6 with a pedestrian dummy in a test. White the interior of the hood was “completely destroyed … the hood on the outside appears good as new,” he said.

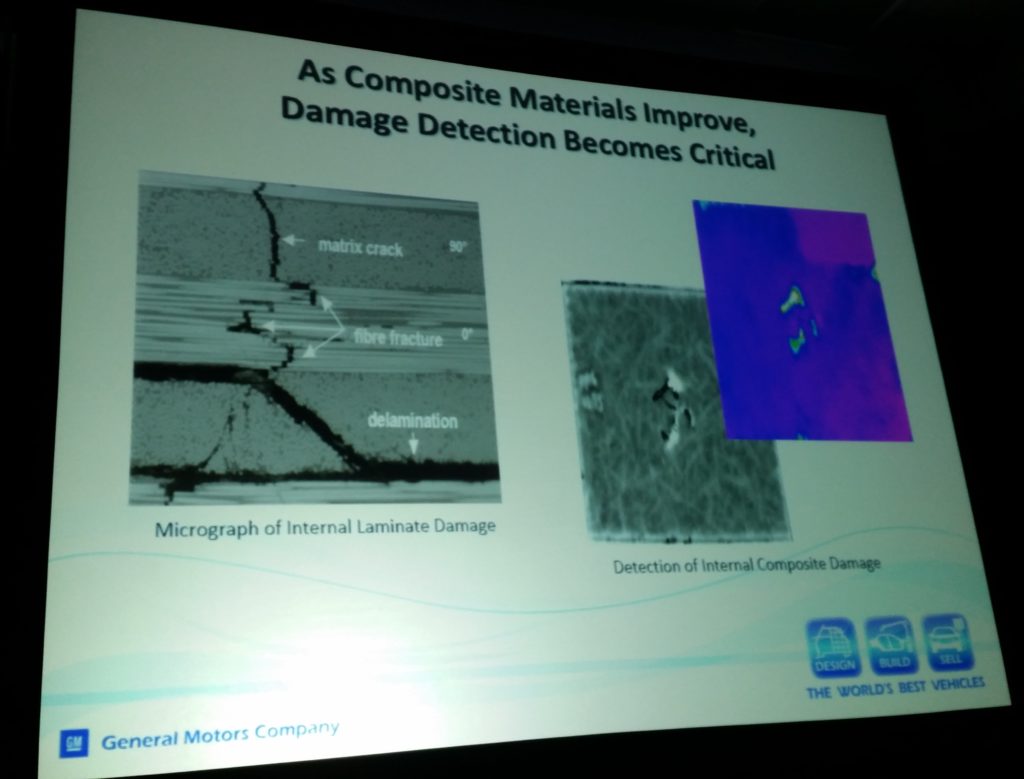

He said in another test, a carbon fiber hood was run into a barrier at 35 mph. It popped back into place, the damage largely invisible to the eye. Tools like a micrograph are necessary to see that something’s wrong, he said. (Which could make photo estimating even more difficult should OEMs replace one or two panels — like some Cadillac hoods — with composites.)

There was “no easy answer” on how to tell if a composite part was undamaged, Voss said. Before composites can truly go mass-market, GM would need to figure out a way for auto body technicians to do so, he said.

However, Voss noted that much “exciting technology” could be used for this purpose, citing dyes as an example.

More information:

“Repair University Live” on Collision Hub Livestream channel, June 21, 2017

Images:

Larry Montanez of P&L Consultants in this screenshot from “Repair University Live” footage demonstrates cracked paint which indicates that the aluminum substrate beneath has microfractures. (Screenshot from Collision Hub video)

This composite hood is damaged, but it doesn’t look it — and without a good means of detecting damage for auto body technicians, composites like carbon fiber might not be able to go mainstream. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News; slide provided by General Motors)

Tools like a micrograph view, left, can be necessary to see that damage exists on a composite automotive part. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News; slide provided by General Motors)