Car-O-Liner, I-CAR discuss pulling vehicles with higher-strength steel parts

By onEducation | Repair Operations | Technology

Higher-strength steels in vehicle structures create new considerations for auto body shops evaluating damage and pulling vehicles, according to a Car-O-Liner expert.

The sheer strength of 980-megapascal and 1,500 MPa parts — some of the stronger grades of ultra-high-strength steel — demands repairers consider the crash energy load path of the vehicle, Car-O-Liner Training Academy manager Mike Hoeneise said in a February Collision Hub video.

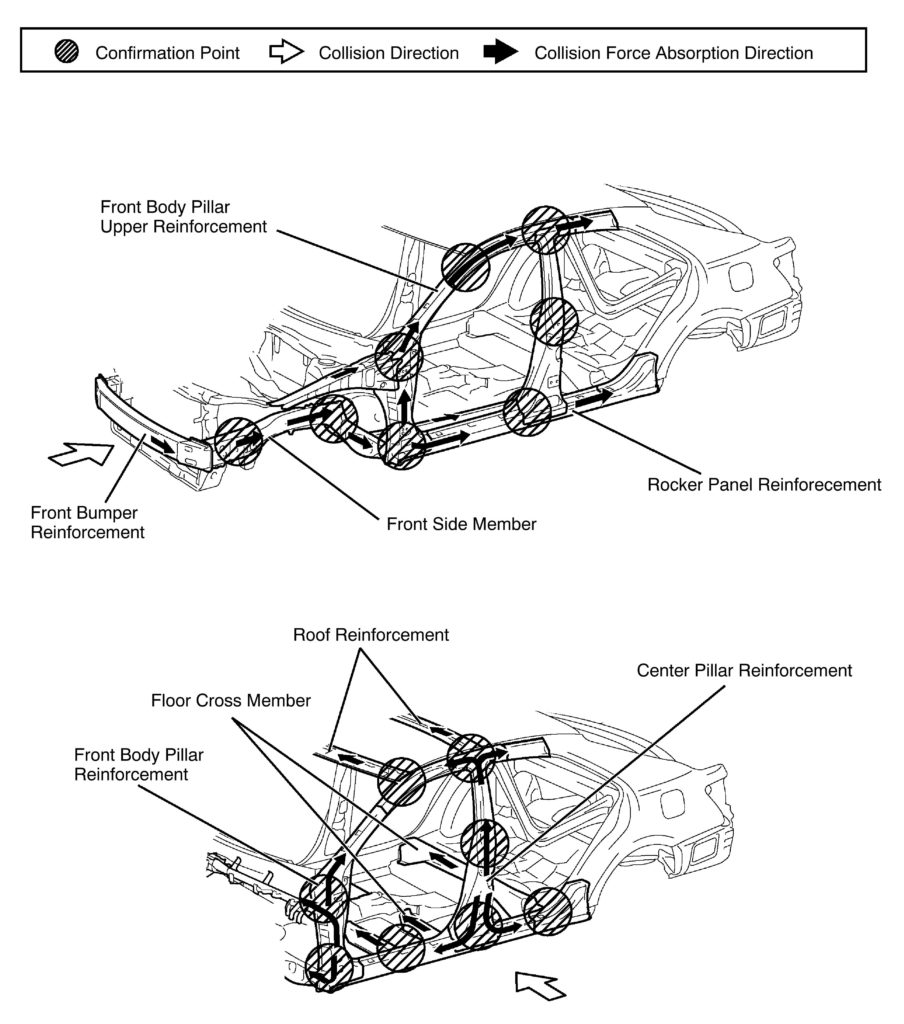

OEMs use a combination of crush zones to absorb energy and higher-strength steel components to distribute it away from occupants within the safety cage. This can lead to a vehicle struck in the front sustaining damage in the rear as the body in white channels the energy of the impact through the car.

Even if fewer parts are repairable because of higher-strength steel-intensive designs, “it’s increased the need to measure,” Hoeneise said.

“It (the higher-strength steel) can have the damage radiate so much deeper into the vehicle,” he said.

The exterior of the vehicle is often made up of softer structures. Such steels “move a whole lot,” but “they’re not reliable damage indicators,” according to Hoeneise.

If you see a damaged fender, the real question surrounds what happened to the parts underneath it, Hoeneise said.

As hopefully everyone knows by this point, higher-strength steels are heat-sensitive. Application of heat changes the metallurgy and reduces the tensile strength of the metal — thereby compromising its ability to protect your customer in a subsequent crash. Thus, you can’t use heat to straighten higher-strength steels, as co-presenter Jason Bartanen, I-CAR industry technical relations director, observed during the broadcast.

However, heat can be used to facilitate a pull — provided the heat-affected parts are removed and thrown away, according to Bartanen and Hoeneise. Hoeneise said this can help “walk out” indirect damage.

If the part that would be heated was damaged in the crash and must be discarded per OEM procedures, “what are we worried about?” Hoeneise said.

“You heat that part as much as you want, as long as you throw it away,” he said.

“What scares me” is when shops heat a part, pull it, and decide “‘It looks great'” and leave the heated area intact, Hoeneise said.

Bartanen stressed that they weren’t talking about heating a part to repair it, only heating parts that would be thrown away.

Hoeneise also said shops should make sure the heat didn’t affect the area the shop intended to keep, and parts that would be compromised should be removed first. Bartanen said that for this reason, heat couldn’t be used to pull a part on the side of the vehicle if a 1,500 MPa B-pillar reinforcement one planned to keep was behind it. (The sides of a vehicle are going to be particularly heat sensitive, given the use of unified “door rings” or similar separate ultra-high-strength steel components on the roof and frame rails and A- and B-pillars.)

In a similar vein, Hoeneise said a repairer could for pulling purposes “overbuild” a part they planned to discard anyway.

He gave the example of using the plate at the end of a front frame rail featured on the show as a “handle” for a pull. There was an “excellent chance” that the factory welds would tear during the process, according to Hoeneise. However, he could add more welds to the plate to keep it intact long enough to make the pull, he said; the component was going to be removed and thrown out anyway, Bartanen said.

Higher-strength steels might also affect one’s process by either overworking a frame machine or causing it to work harder than was necessary, according to Hoeneise. “It gets to be too much,” he said, noting that he gets nervous approaching capacity.

Hoeneise and Bartanen’s points about only heating parts that will be thrown away brings to mind a similar instruction by FCA body, chassis and paint global service lead Dan Black during a July 2017 Guild 21 call.

FCA in 2010 banned using heat on any part that you’re not going to throw away and replace.

“We must have a service component available to replace that component that you are heating,” Black said during the 2017 call. “That’s essential.”

If FCA doesn’t sell a service part or have a sectioning procedure, then you’re out of luck and might have to proceed to full-frame replacement, Black indicated. He said instances where an OEM doesn’t sell a replacement part are intentional, stemming from “a safety-type concern from the OEM.”

When a frame is repairable, shops must still take care not to expose the vehicle to excessive heat during that process. FCA publishes specifications for welders, and it can demand skip-stitch welds to minimize the heat-affect zone, according to Black. He also warned shops never to use an oxy-acetylene torch to remove a damaged RAM frame rail tip because of the heat; repairers must use equipment such as plasma cutter, die grinder or reciprocating saw to protect the other rail from excessive heat.

More information:

“Structural Anchoring And Pulling Strategies From I-CAR”

Collision Hub YouTube channel, Feb. 24, 2018

FCA via VeriFacts Guild 21, July 13, 2017

Images:

Jason Bartanen, I-CAR industry technical relations director, discusses how heat can be used in the pulling process — provided the heated part is discarded — during a February 2018 Collision Hub video. (Screenshot from Collision Hub video)

OEM damage diagnosis guidelines for a 2007-11 Toyota Camry, accessed April 3, 2018, indicate energy flow during certain collisions. (Provided by Toyota)