Army ‘cold spray’ tech an intriguing idea for auto body industry

By onAnnouncements | Repair Operations | Technology

Call it the military’s body filler.

The Army last month reported it had developed a “cold spray” process allowing it to refurbish worn steel Bradley 25mm turret gun mounts for $1,000 a repair — a much more attractive option than buying a new mount for more than $25,000 or forcing a supply chain to stockpile replacements.

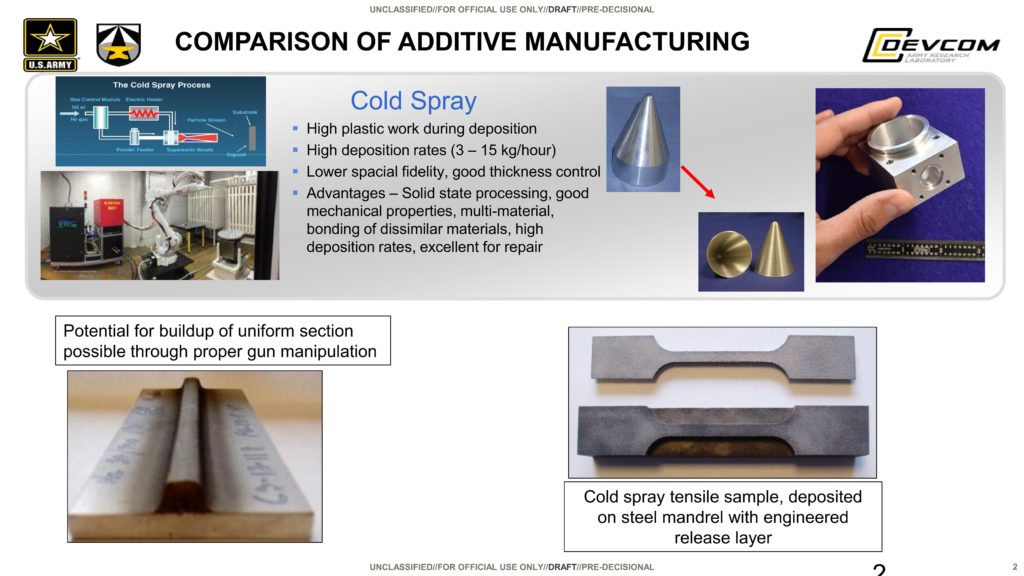

“Cold spray is an emerging technology that will enable the Army to reclaim worn components that were previously replaced with new parts. This new technology reduces lifecycle cost and improves systems availability,” Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory materials engineer Gehn Ferguson said in a statement.

Cold spraying involves blasting micron-sized particles of metal onto a substrate at a high velocity, according to the Army.

“The accelerated particles impact and bond to the surface, resulting in a buildup of the sprayed material,” an Aug. 21 CCDC article states. “Both the sprayed particles and the target surface remain solid during the process.”

John La Scala, ARL associate division chief for materials and manufacturing sciences, said substances including aluminum, tantalum and chrome alloys could be applied through cold spraying.

“It’s not just steel,” he said in an interview Sept. 4.

The user can even pick out powders within a category of metal to ensure the resulting cold-sprayed surface has desirable characteristics, La Scala said. At one point, he described a powder tailored to the degree of tiny particles coating the outside of a larger particle.

While the equipment being used by the U.S. Army CCDC Army Research Laboratory is likely too pricey for a collision repairer for now, an expert said versions with reduced capabilities might be available to the private sector at a lower cost.

ARL cold spray lead Aaron Nardi said they typically work on the highest-performance applications, such as aerospace or defense. Wear and impact resistance are “super-critical.”

Thus, he’s working with top-end cold spray hardware costing $200,000-$300,000. Systems exist on the market in the $100,000 range, but they lose some of the capability and output properties, he said. In the low $200,000s, a cold spray system basically would have the full range of capabilities, he said.

However, Nardi also pointed out that job shop companies exist to subcontract the cold spray work, which would allow a client business to employ the procedure without incurring capital expense firsthand.

“They could still take advantage of it,” Nardi said. He said “there’s actually quite a few” companies who can serve as a cold-spraying subcontractor.

Both robotic and hand-held cold spray applicators exist, according to La Scala. He also said some kind of recycling system might need to be in place to capture particles and keep them out of the sprayer’s lungs.

The material being cold sprayed varies in cost, as you’d expect. Nardi described a range of between $10-$150 a pound — though he also noted that the amount needed could be less than a a pound.

There’s also the cost of the gas used in the process, which passes through the system at a high rate. Nitrogen or helium are possibilities, Nardi said. However, he said nitrogen could be had fairly cheaply, and even the air itself (which is mostly nitrogen) could be used as a replacement. Compressed air can deliver high-quality cold spray repairs, he said.

The applications, range of metals, the possibility of using job shops, and the nature of technology to decrease in cost would seem to make cold spray a process to watch in the collision repair industry.

Uses in the military

So far, the “vast majority” of military cold spray usage had been akin to body filler and nonstructural, Nardi said.

Cold spray work involved filling in damage and adding layers of substrate for better wear or corrosion performance, according to Nardi. He said the system could be used to repair a crack, but it was a “much bigger challenge” to join two surfaces with it. (Though they have used cold spray to join dissimilar materials before.)

Nardi at one point described a project related to helicopter fleet magnesium gearbox housings costing between $20,000-$200,000 each. Corrosion had led to such housings being junked or shelved, but cold spraying aluminum on them allowed several to be restored and returned back to the fleet, according to Nardi.

Asked if automotive OEM e-coating could be restored through cold spray, Nardi said the short answer would be yes. Aluminum or zinc could be sprayed upon steel, and the military has done such an application on areas where it needed “local galvanizing,” according to Nardi.

“It can definitely be done,” he said.

“While the project initially began as a way to repair gun mounts, the material used in the cold spray process is much more durable, which suggests it could even be used to extend the life of new gun mounts,” the CCDC wrote in its article about the Bradley mounts.

“Cold spray is also being evaluated for use with other applications, including the ability to repair corrosion on a combat vehicle surfaces and possibly to coat the interior of cannon barrels. For example, if the inside of a cannon barrel can be effectively coated with tantalum, which is a very durable material, its service life can be extended.”

A “high-value” project involved an aircraft carrier bronze housing spanning two feet weighing about “two tons,” Nardi said. The only replacement part was halfway around the world and already installed on another system, and a new part would require more than a year and cost $500,000.

Cold-spraying about 30 pounds of bronze and grinding off some other material led to the part being restored in three weeks and got the aircraft carrier out of drydock, he said.

While most applications were nonstructural, the process has successfully been used on “absolutely a flight-critical part,” Nardi said.

The long shaft on an Apache helicopter has a small nickel-plated surface which is a pain to restore traditionally, according to Nardi. You have to mask the rest of the part, dip the component into a bath large enough to accommodate it, strip off the masking and heat-treat the part — all just to replate a “little band” with nickel, he said.

Cold spraying let the military apply nickel to the surface without having to mask anything, he said.

Nardi said military equipment OEMs are on the whole willing to work with the armed forces on validating the cold spray repairs. While acknowledging the military’s clout as a purchaser might incentivize a manufactuer to cooperate, Nardi noted that the suppliers recognize a benefit in helping: Any repairability lessons they learn in working with the military can be applied to the manufacturer’s traditional commercial business operations.

“Generally, yes they are receptive,” he said. Each branch’s suppliers have their individual nuances, but on the whole, the manufacturers are “pretty receptive,” he said.

Applying the metal

Nardi said the best cold spray repairs are done by removing the damage to the substrate and creating a smooth surface, then depositing the sprayed material. However, it doesn’t have to be completely smooth, he said.

It’s not a situation like you’d encounter with an adhesive, where the surface had to be roughened first and the repairer hopes the bond is good enough, Nardi said. The cold spray process is more like cold welding and delivers “very, very high bond strength,” he said.

Curing is “pretty instant,” according to Nardi. Generally, between 1-10 pounds of material can be laid down per hour, and a typical repair involving filling in a divot on aluminum might take 5-10 minutes, he said.

La Scala said the new surface created by cold spraying wouldn’t be as smooth as a Class A finish — but you could sand it down to one.

Technically, cold spraying isn’t really cold, according to Nardi. The system does use hot gas to accelerate the particles at the substrate, but the particles are solid-state and “instantly cool” from the 200 degrees Celsius (392 Fahrenheit) they are at impact.

The surface temperature of the part being repaired likely won’t exceed 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit), Nardi said. Blowing a little air across it can cool it, he said. Nardi said the heat from the gas itself shouldn’t warm up the substrate excessively either.

This also seems promising for collision repair, considering that substrates like higher strength steel can be heat-sensitive. GM’s heat repairability matrix, for example, even limits mild steel heat applications to 650 Celsius (1,200 Fahrenheit) for a maximum of two times at no more than 90 seconds each.

More information:

“Army develops cold spray technology to repair Bradley gun mounts”

U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, Aug. 21, 2019

Images:

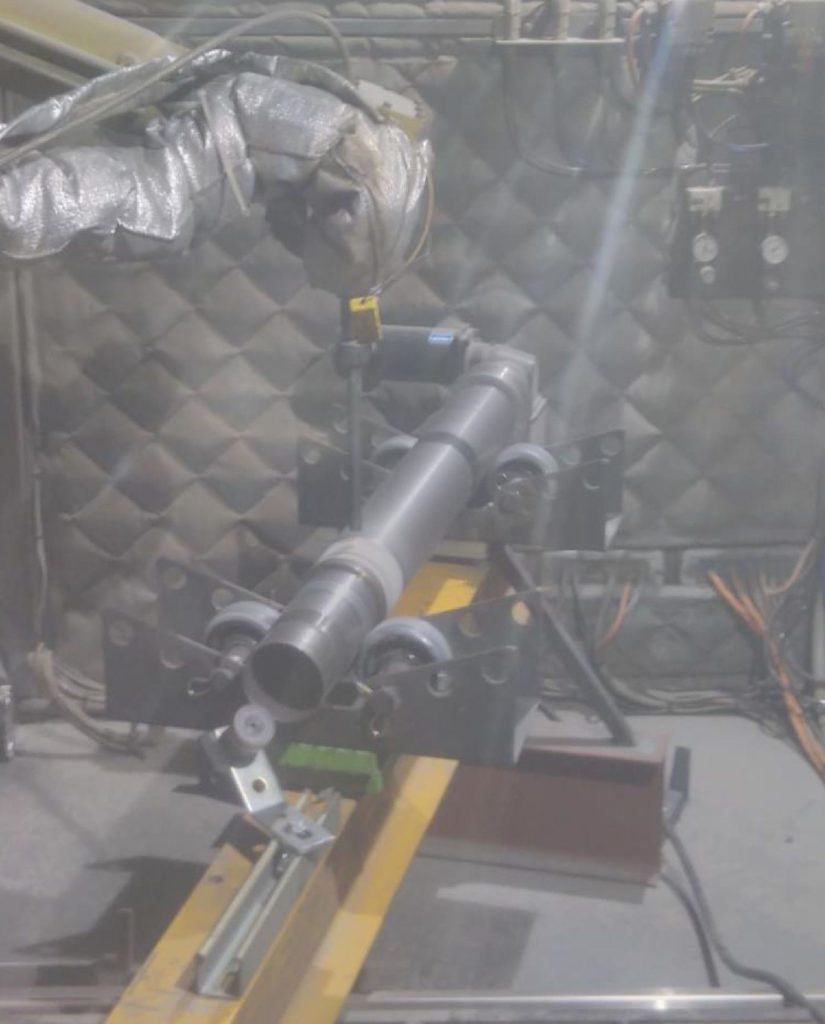

The U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory restores the internal diameter of a Bradley gun mount exit throat with the cold spray process. (U.S. Army)

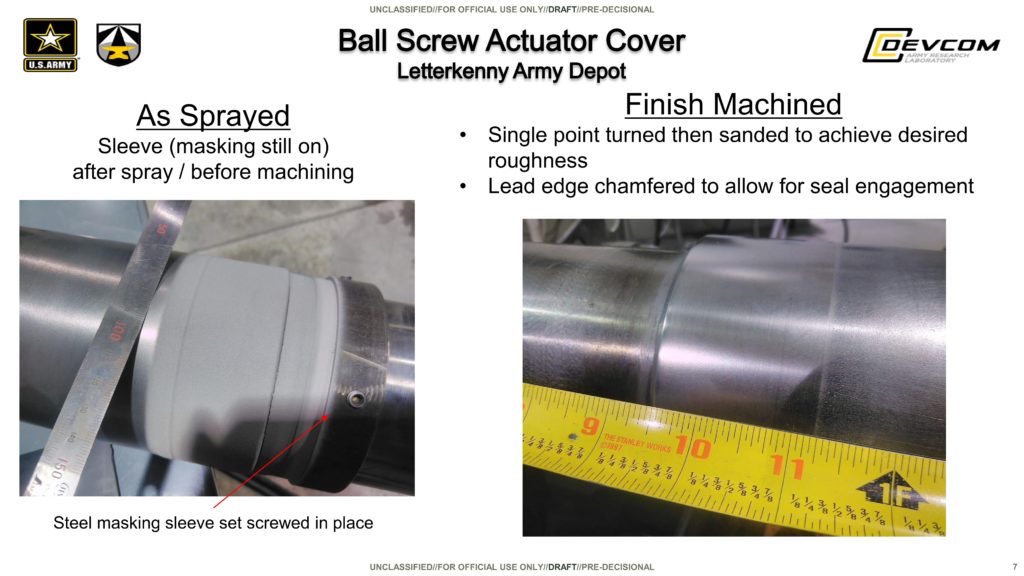

Cold spraying occurs on a bell screw actuator cover. (Provided by U.S. Army)

Properties of the cold spray process are shown in this slide. (Provided by U.S. Army)

The gun mount on an M2 Bradley is shown on the actual vehicle. (U.S. Army)

An expert said cold spraying couldn’t deliver a Class A surface — but the particles laid down could be sanded down to one. A similar concept is demonstrated in this slide. (Provided by U.S. Army)