Megatrends USA: How the car of tomorrow will be welded, glued

By onEducation | Technology

As materials in autos continue to grow lighter and more complicated, traditional joining methods might grow less relevant in the factory and in collision repair shop — and even auto industry experts are trying to wrap their brains around the best new methodology for it.

“We’re all learning how to join at the same time,” Shiloh Industries CEO Ramzi Hermiz said at last week’s Megatrends USA conference in Dearborn, Mich. Read more RDN coverage here.

As carbon fiber, magnesium, aluminum, high-strength steel — and even plastic — advance and make up more and more of a vehicle’s components, techniques like laser joining, friction stir welding, mechanical fastening, tempering, and even glues (they like to call them adhesives) are going to be used, experts at Megatrends said.

Interestingly, while Ducker Worldwide experts offered predictions for the future of various future materials, they couldn’t talk about what joining methods they saw “winning” as they’d been contracted to study that question for various industry players, Managing Director Scott Ulnick told Repairer Driven News. (Ducker project director Abey Abraham did observe that different manufacturers are trying different routes.) That’s intriguing.

Nonadhesives

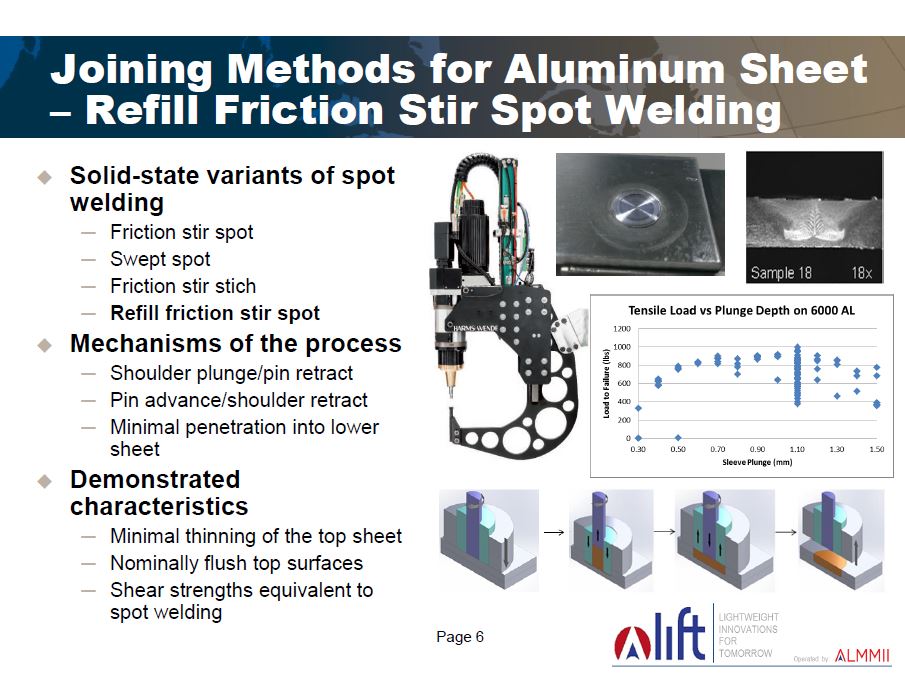

EWI resistance and solid-state welding technology leader Jerry Gould discussed the nonadhesive forms of welding necessary to connect traditional materials to each other in future vehicles. See his presentation slides here.

High-strength steels can be joined by tempering the area being welded during the process: Apply heat quickly, let it cool for about a second, and then temper it with another burst of heat.

Those steels can also be joined by an advanced gas-metal arc welding method, such as using a reciprocating wire feed or hybrid laser welding, Gould said.

For joining aluminum, options include friction stir welding — which allows for a nice flush fit with the top sheet — and resistance spot welding, though electrode wear can be a hassle.

But another way is just to use a mechanical fastener, such as a self-piercing rivet, according to Gould. A short burst of heat — such as 350 degrees for a second — can also assist with mechanical joining, giving more flexibility to metals like magnesium or aluminum and keep the penetrating item from cracking it, he said.

Even aluminum and steel can be welded together — it’s been done for years in propeller shafts, Gould said. Friction welding is one method of doing so, he said. The trick is to keep thermal cycles short.

Gould said after his presentation that it was intended to discuss joining at the OEM level, not the repair shop. However, some of these techniques, such as in-situ tempering and self-piercing rivets, can be seen in shops today, and advances in technology could bring more factory-level methods into shops in the future.

EWI resistance and solid-state welding technology leader Jerry Gould discussed the nonadhesive forms of welding necessary to connect nontraditional materials to each other in future vehicles. His slide on aluminum stir welding is shown here. (Provided by EWI/LIFT))

Glues

Much of the rest of the Megatrends joining discussion discussed adhesives to join mixed materials that are stronger but more finicky to work with. This was no doubt partly because the forum invited experts from chemical engineering community to speak, but the merits were pretty clear.

Adhesives prevent corrosion issues when aluminum, steel, and magnesium touch — and they’re even used to fill the space between physical connectors for this purpose — they can be stronger than spot-welds since they cover a larger surface area, and they’re lighter than the metals added in traditional joining methods.

Henkel North America automotive Vice President Dan Wohletz noted IHS and Wall Street Journal work that found that a vehicle today has about 27 pounds of adhesive inside — but eliminates multiple times that much in overall weight. Dow Automotive global strategic marketing manager Ana Wagner said that every meter of adhesive cuts 0.6-1.1 kilograms of mass. (See Wohletz and Wagner’s presentations here and here.)

Adhesives are likely going to take on a larger and larger role in the collision repair process as materials evolve. Ford relies heavily on self-piercing rivets in the aluminum F-150 but uses glues as well, (Wagner observed that Dow supplies a structural bonding agent to Ford.), and repairers will use both. General Motors suggests adhesives for fixing the high-strength steel Chevrolet Silverado, and glues are a vital part of the carbon-fiber BMW i3 repair process.

As a car is “only as strong as your rivet points,” according to Wohletz, the continuous bond and larger surface area of an adhesive joining allows an impact to have less of an effect on the vehicle, he and Wagner said.

Adhesives also can yield a quieter ride, Wohletz observed.

Henkel North America automotive Vice President Dan Wohletz noted IHS and Wall Street Journal work that found that a vehicle today has about 27 pounds of adhesive inside — but eliminates multiple times that much in overall weight. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)

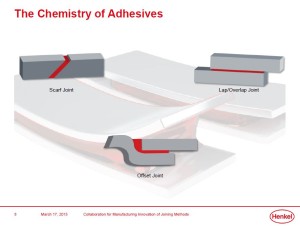

Though a variety of joint shapes can be glued together, design constraints include the size of the gap, the expansion of the adhesive, and curing factors, according to Wohletz.

Wohletz said he couldn’t speak to the state-of-the-art of weld-through adhesives — “I’m not in the weeds there” — but he did note that all structural connections are weld-through.

Adhesives themselves have been used in vehicles since the 1960s, when plastisols/epoxies were introduced to the hood assembly and cut “fluttering,” according to Wohletz’ presentation.

By the 1980s, hard powertrain gaskets were swapped out in favor of cheaper, better silicon ones, according to Wohletz.