Update: Fla. judge kills Miss. shops’ antitrust claims against insurers; no word on other allegations

By onInsurance | Legal | Repair Operations

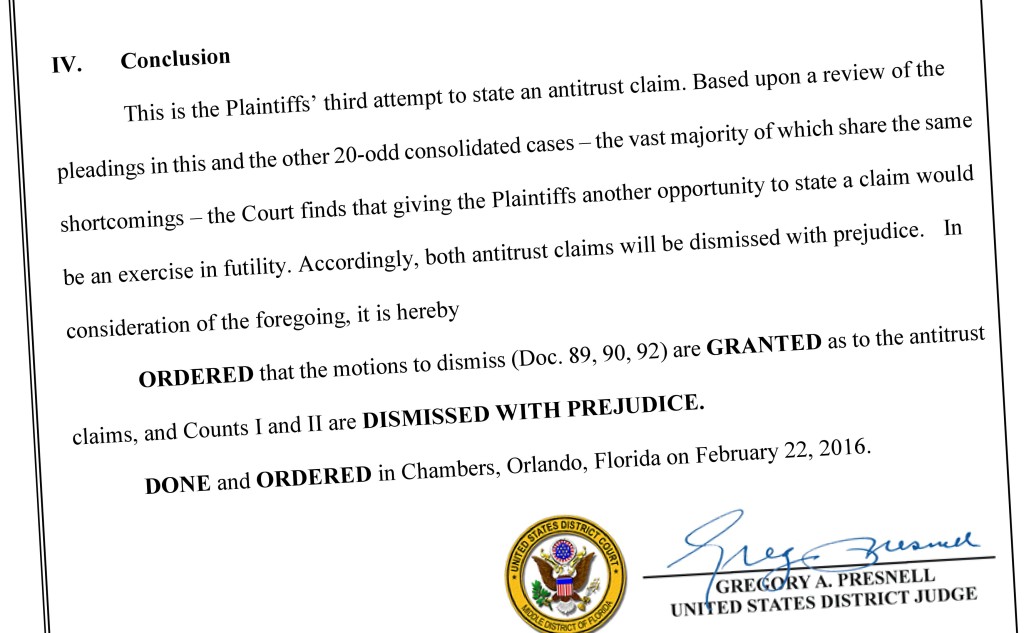

A Florida judge on Monday threw out federal antitrust and boycott allegations brought by 26 Mississippi collision repairers against some of the largest auto insurers in the country.

The Sherman Antitrust Act claims were dismissed with prejudice, which means there’s no chance they can be refiled, only appealed.

However, Middle District of Florida Judge Gregory Presnell hasn’t yet ruled on the other claims in the lawsuit — including a potentially stronger steering case (legally known as “tortious interference”).

U.S. Magistrate Judge Thomas Smith last week recommended three shops’ allegations of tortious interference– two against Progressive and one against State Farm — had enough evidence to survive a motion to dismiss.

The incomplete dismissal might for now be a ray of hope for shops in Mississippi and more than a dozen other states whose cases were placed before the judge. It’s certainly a better near-term outcome than the fate of the related A&E v. 21st Century, a Florida case Presnell threw out for good in a single September 2015 ruling. That case, the Mississippi Capitol Body Shop et al v. State Farm et al, and many of the others were prepared by Jackson, Miss.-based Eaves Law Firm.

As noted above, there’s also the possibility the shops could appeal. Though the Florida shops haven’t yet done so, others at an earlier stage of their cases have asked the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals to intervene.

“We’re disappointed,” attorney John Eaves Jr. said Wednesday. However, he was heartened by Smith’s steering recommendation, saying “the biggest part of the case is going forward”

Eaves said the shops would appeal Presnell’s ruling and that in the A&E case as well.

Still, the ruling Monday doesn’t look good for many of the other 20-plus cases with similar antitrust arguments.

“This is the Plaintiffs’ third attempt to state an antitrust claim,” Presnell wrote. “Based upon a review of the pleadings in this and the other 20-odd consolidated cases – the vast majority of which share the same shortcomings – the Court finds that giving the Plaintiffs another opportunity to state a claim would be an exercise in futility.”

Collusion or parallel?

The 26 Mississippi shops in Capitol couldn’t overcome a tough antitrust hurdle: Are similar actions by similar businesses collusion or merely just smart competition?

“The actions allegedly taken by the Defendants in this case, such as paying the same labor rates, refusing to pay for the same list of procedures, and requiring the use of lower-quality parts, are not enough, on their own, to constitute a violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act,” Presnell wrote Monday.

The shops had to prove either that everyone named as a defendant acted against its self-interest or behaved in a way to suggest another “plus factor,” according to Presnell.

In this case, the repairers had alleged that an insurer couldn’t underpay shops, refuse to pay for operations truly needed for a “pre-accident condition” repair and mandate non-OEM parts unless it was secure that the other insurers would follow suit. Otherwise, the shops argued, it’d quickly lose customers to those who paid shops to do a better job.

“This argument is simply not plausible. The ‘underpaying’ which is seen by the Plaintiffs as ultimately harmful to the self-interest of the Defendants is simply the buyer-side version of the profit-maximizing behavior described approvingly by the Supreme Court,” Presnell wrote. “… If the oligopoly has market power – as alleged in this case – then it is consistent with that power for its members to observe price parity. The possible eventual loss of customers resulting from such a practice is nothing more than speculation.”

A desire to make more money (by spending less on repairs) can’t count either as a “plus factor,” Presnell ruled.

“If the existence of a profit motive was enough to make it plausible that the defendants had colluded to fix prices, then essentially every alleged price-fixing agreement would survive a motion to dismiss,” he wrote.

Shops had pointed out that State Farm, the No. 1 auto insurer in the country, conducts allegedly flawed market surveys to determine what it’ll pay. Once it changes its rates, the other insurers allegedly quickly follow suit.

For example, State Farm bumped its labor rate ceiling $2 to $44/hour, and Shelter and USAA did the same weeks later. After it upped them again to $46 in 2012, seven other insurers, including Shelter, USAA and State Farm’s closest competitors Allstate and GEICO did too.

Presnell wrote that since not all the 17 defendants weren’t shown in the lawsuit to have matched rates, the allegation couldn’t stand. He didn’t say why it couldn’t stand for the seven insurers in the $46 example or even just Shelter and USAA, which are in both. He also appears to have ignored or rejected as too broad the lawsuit’s allegation that the “Defendants all raise their ‘market rates’ within days of State Farm raising their rates.” (Emphasis added.)

In any case, according to Presnell, there’s no proof in the case that State Farm keeps its prices secret — though the shops call it “unpublished” (emphasis in original) — or discussion of “why State Farm would have any incentive to try to keep the rates it pays for repairs secret from its competitors.”

“And given that those rates would be known by, inter alia, every repair shop in the state, it would not appear likely that State Farm could keep them secret, even if they had a reason to do so,” he continued. (DRP most favored nation clauses would also tell insurers what the lowball labor rate was for an area.)

Apparently, Presnell didn’t notice a double standard here.

“Defendants have threatened Plaintiff shops and others that if they discuss labor rates with each other, they will be price fixing and breaking the law. Statements to this effect have been made by Defendants State Farm, GEICO, Progressive and Allstate specifically but not limited to Plaintiffs Capitol, Clinton, Bill Fowler’s, Smith Brothers and Bolden,” the shops wrote.

As for the federal boycott claim, he argued there wasn’t any evidence that any of the insurers had flat-out refused to do business with a particular shop.

“At best, the Defendants argue, the Plaintiffs have included in the Second Amended Complaint some allegations of a particular insurer attempting to steer its insured from a shop operated by one of the Plaintiffs to a different shop that had a relationship with the insurer,” Presnell wrote.

Featured image: Part of the ruling in Capitol v. State Farm is shown. (Provided by Middle District of Florida)