Self-piercing rivets get another boost as Stanley enters North American automotive market

By onBusiness Practices | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

In a potential sign of more mixed- or advanced-material construction ahead, Stanley Engineered Fastening announced last month it would start selling “next-generation self-pierce rivets” in North America for the first time.

The company, which was slated to present the technology last month during the Global Automotive Lightweighting Material conference, called the technology “well-established in Europe,” For example, A Wednesday SAE Automotive Engineering piece notes that the new Range Rover Sport has 3,648 Stanley SPRs.

In North America, SPRs notably are already part of the joining for the aluminum (and steel) current-gen Ford F-150 and Cadillac CT6, and they’re one of the many new joining techniques even non-luxury collision repairers might need to know as OEMs look at new methods of cutting weight but preserving (or improving) crashworthiness.

A spokeswoman for Stanley provided the following definition:

Self-pierce riveting (SPR) is a process used to join two or more layers of materials without a predrilled or punched hole. This is done by driving a rivet through the top layers of material and upsetting the rivet in the lower layer (without piercing the layer) to form a durable joint. SPRs can effectively join together parts made of aluminum, steel, plastics, composites or a combination of materials.

Stanley’s news release appeared to target OEMs seeking factory options, but that has a trickle-down effect to the aftermarket. Components which took a self-piercing rivet on the assembly line might demand repairers use the joining technique, or at least some other mechanical fastener.

According to Stanley, those OEMs likely will use more self-piercing rivets.

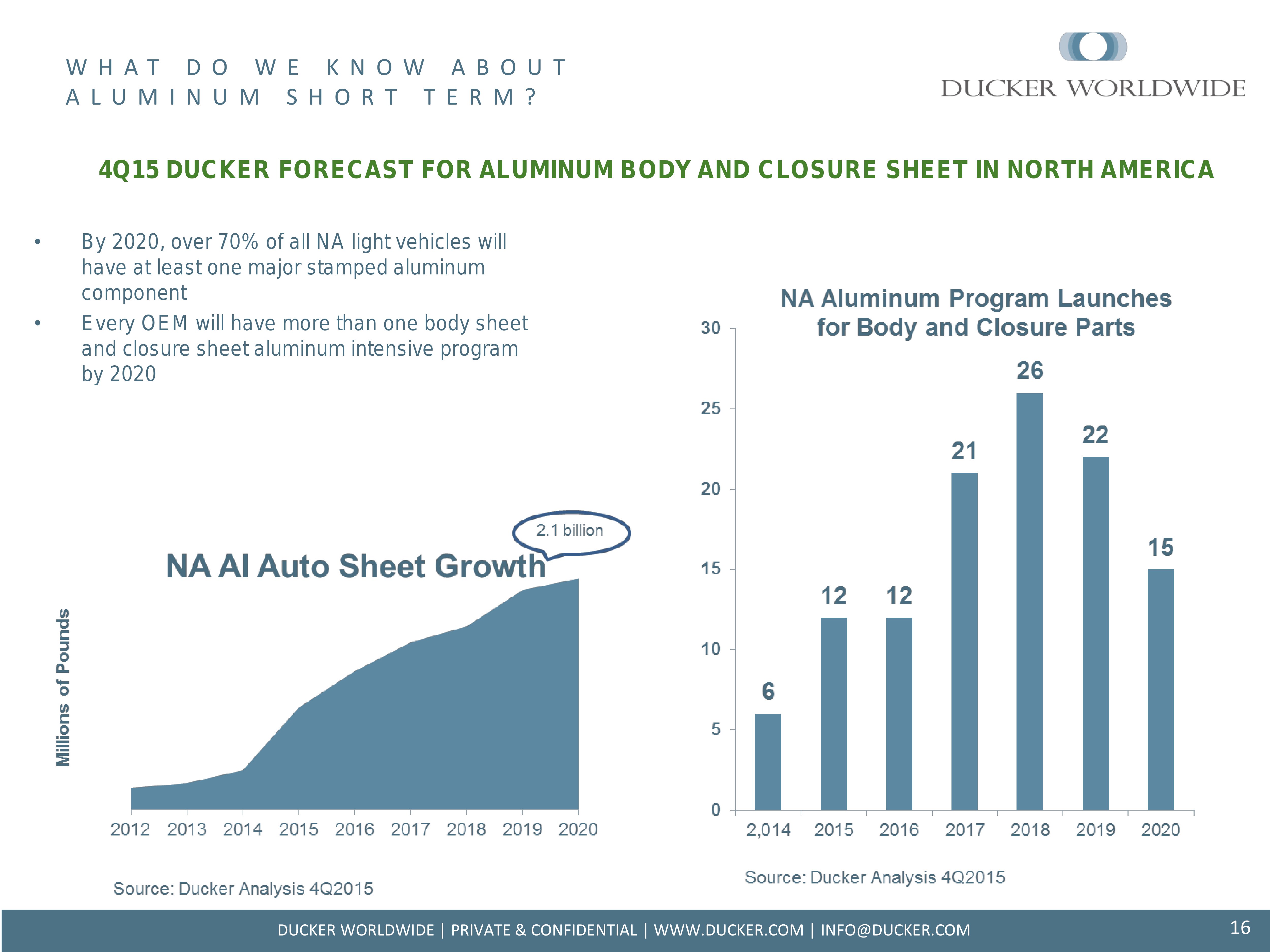

“Demand for SPRs, which already are well-established in Europe, is on the rise in North America as automakers increasingly adopt materials such as aluminum, which is forecast to grow in the North American automotive industry,” Stanley wrote.

It cited one of Ducker Worldwide’s aluminum forecasts, which according to Stanley projected aluminum sheet demand leaping from less than 200 million pounds in 2012 to the billions within a decade.

“Within the same timeframe, every leading automaker is expected to have an aluminum body program in place, according to the study,” Stanley wrote. Here’s similar data from a Ducker SAE presentation earlier this year:

Stanley said it already had heard interest from “several major North American automakers” who wanted to add materials like aluminum and carbon fiber.

“Whether joining aluminum, steel, plastics, composites, or combinations of materials, SPR is ideal for joining sheet materials providing a watertight joint,” Stanley Breakthrough Innovation Vice President Siva Ramasamy said in a statement. “SPRs are installed with a servo-driven tool enabling control of the rivet-setting process for uncompromised repeatability. The system provides process-monitoring capabilities, enabling increased productivity and quality.”

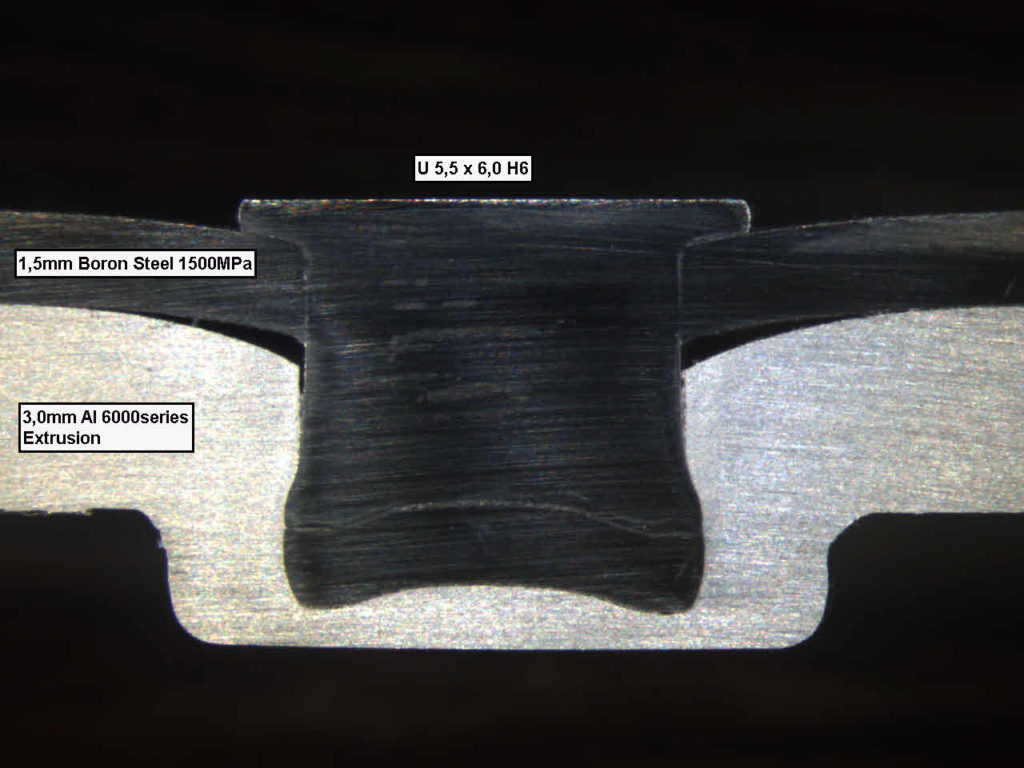

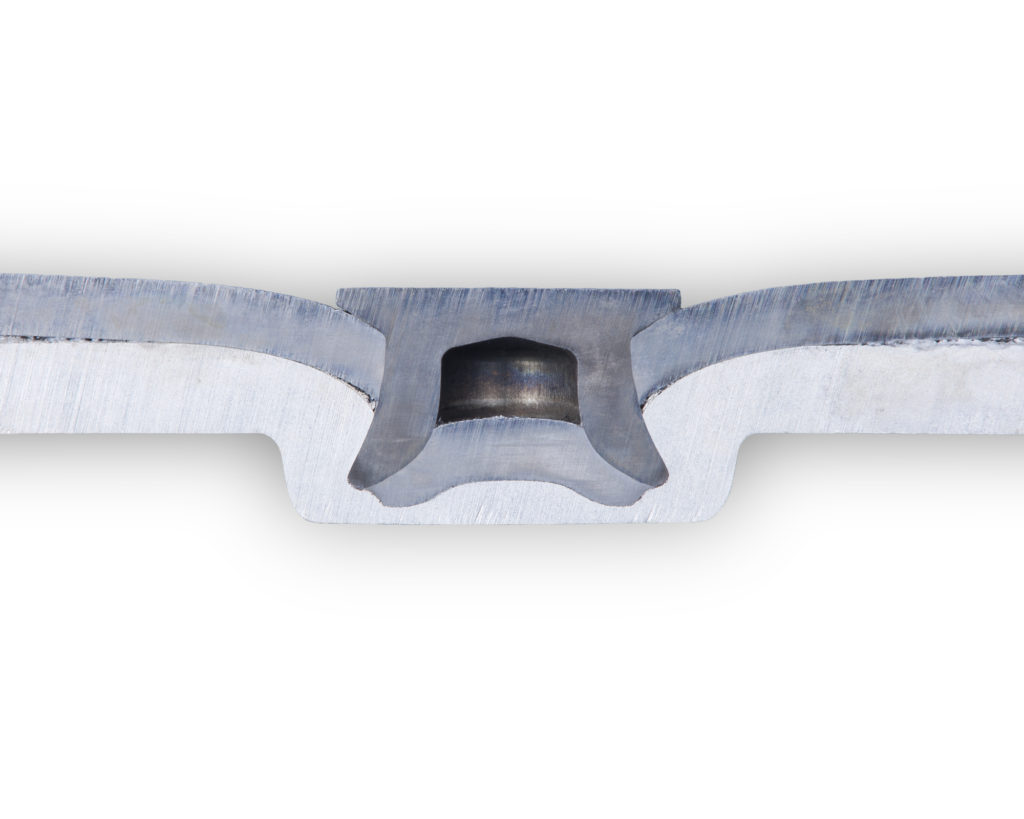

Here’s some examples of self-piercing rivets for those unfamiliar with the relatively new technology, courtesy of Stanley:

Aluminum to ultra-high-strength steel

Aluminum to multiple layers of aluminum

Aluminum to aluminum (top), steel to aluminum

Aluminum to high-strength steel

Images:

A self-piercing rivet joins aluminum to aluminum (top) and steel to aluminum. Stanley calls the joining watertight, a useful means of warding off galvanic corrosion from dissimilar metals. (Provided by Stanley)

This Ducker Worldwide analysis shown in an SAE webinar indicates the potential demand for aluminum ahead. (Provided by Ducker Worldwide)

A self-piercing rivet joins aluminum to ultra-high-strength steel. Stanley calls the joining watertight, a useful means of warding off galvanic corrosion from dissimilar metals. (Provided by Stanley)

A self-piercing rivet joins multiple layers of aluminum. (Provided by Stanley)

A self-piercing rivet joins aluminum to high-strength steel. Stanley calls the joining watertight, a useful means of warding off galvanic corrosion from dissimilar metals. (Provided by Stanley)