Researchers ‘got lucky,’ can create light, strong material graphene out of acetylene gas, spark plug

By onAnnouncements | Education | Repair Operations | Technology

A technique that’s effectively a modified version of a car’s combustion engine might someday create the vehicle’s body panels.

Aerosol researchers at Kansas State University last month reported literally lucking into a means of mass-producing graphene with just hydrocarbon gas, oxygen and a spark plug.

“Their method is simple: Fill a chamber with acetylene or ethylene gas and oxygen. Use a vehicle spark plug to create a contained detonation. Collect the graphene that forms afterward,” KSU wrote in a news release Jan. 25.

KSU calls graphene the “world’s thinnest material” — it’s built out of 1-atom-thick carbon sheets of hexagonally-arranged atoms. And it could be a major contributor to automotive lightweighting if it becomes viable for car bodies. See this great Automotive World 2015 analysis for more on the potential and challenges for graphene composites.

Graphene weighs less but is stronger than the current high-potential composite lightweighting option of carbon fiber — and it’s “200 times stronger than steel,” according to the automaker BAC, which in August 2016 announced it built the Mono supercar’s wheel arches out of carbon-fiber enhanced with graphene.

Graphene also could be useful for other applications, such as electronics.

The KSU team’s method is exciting because it’s so “simple, efficient, low-cost and scalable,” according to the college. Scale is a big one — if you can’t easily and cheaply mass-produce a particular material, it’s likely a nonstarter for an OEM. A lack of access to magnesium, for example, might have kept OEMs from using more of that metal to lightweight vehicles.

“We have discovered a viable process to make graphene,” lead inventor Chris Sorensen said, according to KSU. “Our process has many positive properties, from the economic feasibility, the possibility for large-scale production and the lack of nasty chemicals. What might be the best property of all is that the energy required to make a gram of graphene through our process is much less than other processes because all it takes is a single spark.”

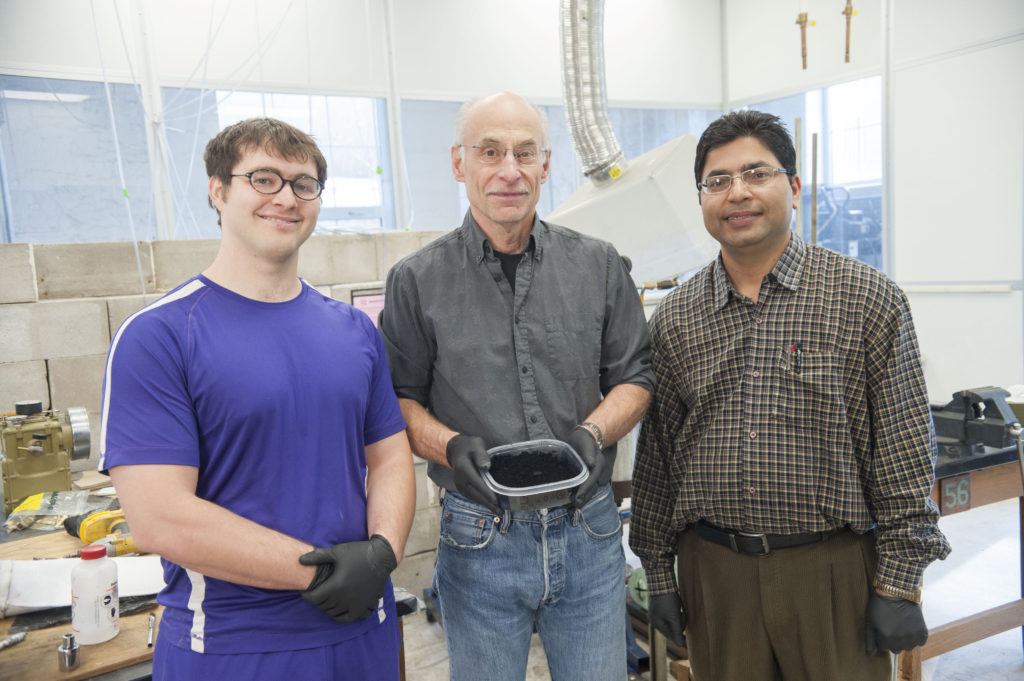

Sorensen, former visiting scientist Gajendra Prasad Singh, postdoctoral researcher Arjun Nepal and physics doctoral student Justin Wright were working on carbon soot aerosol gels created by blowing up acetylene gas and oxygen in an aluminum chamber.

They found aerosol gels resembling “black angel food cake,” Sorensen said. It was actually low-density graphene.

“We made graphene by serendipity,” Sorensen said. “We didn’t plan on making graphene. We planned on making the aerosol gel and we got lucky.”

Blowing stuff up with a spark plug is much simpler, safer and less energy-intensive than trying to cook graphite with dangerous chemicals or cranking up hydrocarbons to 1,832 degrees around catalysts, according to KSU. The yield’s better too.

“The real charm of our experiment is that we can produce graphene in the quantity of grams rather than milligrams,” Nepal said, according to the college.

Next up: Better graphene and more of it, according to KSU.

“They are upgrading some of the equipment to make it easier to get graphene from the chamber seconds — rather than minutes — after the detonation,” the university wrote. “Accessing the graphene more quickly could improve the quality of the material, Sorensen said.”

BAC wrote that it worked with Haydale Composite Solutions on the Mono wheel arches “due to the size and complexity of the part, to thoroughly test the manufacturing process and how the material fitted in with the car.”

“We are pleased to have worked on the design and development of the graphene enhanced carbon fibre materials for the BAC Mono,” Haydale director of aerospace and defense Ebby Shahidi said in a statement. “These initial materials have shown some major increases in impact and thermal performance coupled with improved surface finish and it’s pleasing to see these attributes being demonstrated on such a high performance vehicle as the Mono.

“We look forward to collaborating further with BAC and delivering even higher performance materials and components to increase the performance of this exciting vehicle.”

BAC development director Neill Briggs said “significant weight savings and improving body strength” would produce a better car for customers.

“BAC is uniquely placed in the automotive industry to be able to take innovative steps, and latest work with graphene is further proof of this,” Briggs said in a statement. “This development work is further proof of our ability to work with the very latest materials and innovators. At BAC we don’t wait for new technology to come to us, we actively seek it out and work with the very best in the industry to stay at the forefront of the automotive and motorsport industries.

“Making significant weight savings and improving body strength will allow us to offer improved performance to our customers. This is the latest in a line of ground-breaking innovations on the Mono, and we were delighted to have worked with graphene composite industry leaders, Haydale, on this exciting project.”

More information:

“Physicists patent detonation technique to mass-produce graphene”

Kansas State University, Jan. 25, 2017

“Another world first from BAC with graphene-bodied Mono”

BAC, Aug. 2, 2016

Images:

Kansas State University lead scientist Chris Sorensen holds graphene created while blowing up acetylene gas and oxygen in an aluminum chamber. (Provided by Kansas State University)

BAC and Haydale Composite Solutions created graphene-enhanced carbon fiber wheel arches for the BAC Mono supercar. (Provided by BAC)

From left, Kansas State University doctoral student Justin Wright, lead scientist Chris Sorensen and postdoctoral researcher Arjun Nepal created graphene while blowing up acetylene gas and oxygen in an aluminum chamber. (Provided by Kansas State University)