IIHS on aftermarket parts: ‘Some are good and some are bad’

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

An Insurance Institute for Highway Safety analysis of attorney Tood Tracy’s data concludes that while the presence of aftermarket parts might have affected the 2013 Honda Fit’s 40 mph moderate-overlap crash performance, the results would only apply to the specific parts Tracy used in the test.

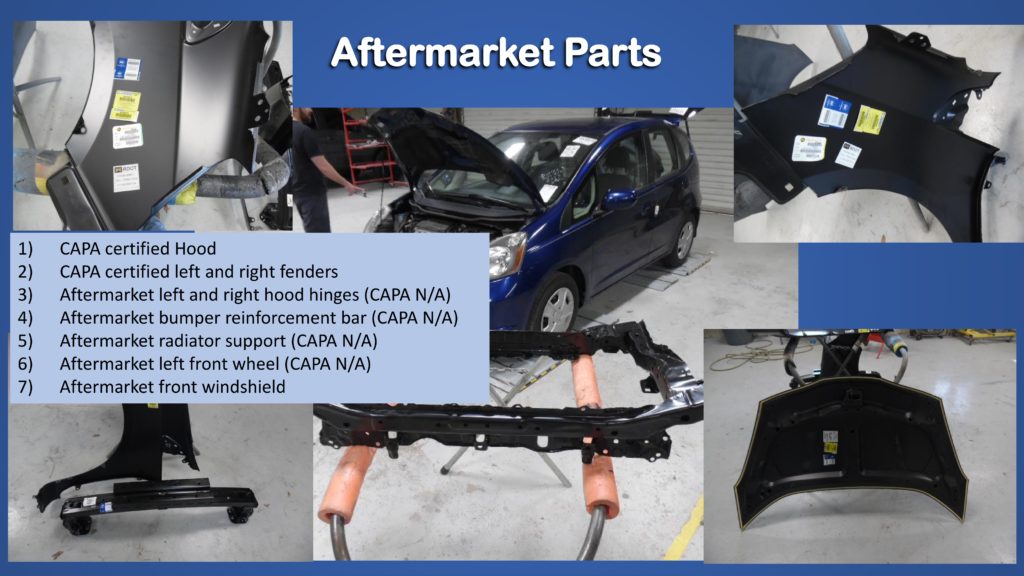

Tracy’s experiment involved Karco Engineering subjecting a 2013 Honda Fit with aftermarket parts, a 2009 Honda Fit repaired like one owned by two Tracy clients, and a control 2010 Fit to a 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test. (For crash testing purposes, the 2009-13 Fits are structurally identical.)

The 2013 Honda Fit’s imitation components included Certified Automotive Parts Association-certified fenders and a CAPA-certified hood; a NSF-certified bumper reinforcement beam; an uncertified aftermarket radiator support, windshield and drivers-side front wheel; and two uncertified aftermarket hood hinges, according to experiment contributor Burl’s Collision.

“The use of particular non-OEM repair parts in the 2013 Fit may have contributed to differences in crash test results compared with the control tests,” the IIHS wrote. “However, these results pertain only to the parts used in the Karco Fit tests in question, and not the use of non-OEM parts in general.”

This is a fair point. But in this case, it also feels like double standard, for the IIHS in the paper also concludes that sweeping categories of aftermarket parts are safe based on similar scattered tests of individual parts on a single vehicle.

“The issue of the safety of aftermarket repair parts warrants serious study, and it is one that the Institute has examined several times during the past 30 years. Aftermarket parts fall into two categories: cosmetic and structural,” the IIHS wrote. Our previous research has shown that cosmetic parts don’t alter crash test results, so where they are sourced — whether aftermarket or OEM — is irrelevant. Fenders, quarter panels, door skins, bumper covers and trim aren’t responsible for safeguarding occupants in a crash. That is the job of structural parts.

“Structural parts make up the front-end crush zone and safety cage. The crush zone absorbs crash energy, and the safety cage helps protect occupants by limiting intrusion. Replacement structural parts must exactly replicate the original parts to preserve the integrity of a vehicle’s crashworthiness, whether they are sourced from the OEM or an aftermarket supplier. Our research shows that some aftermarket non-OEM parts can meet these requirements. We continue to stand by that conclusion.”

We discussed some of these results and conclusions with IIHS Chief Research Officer David Zuby in an interview Thursday.

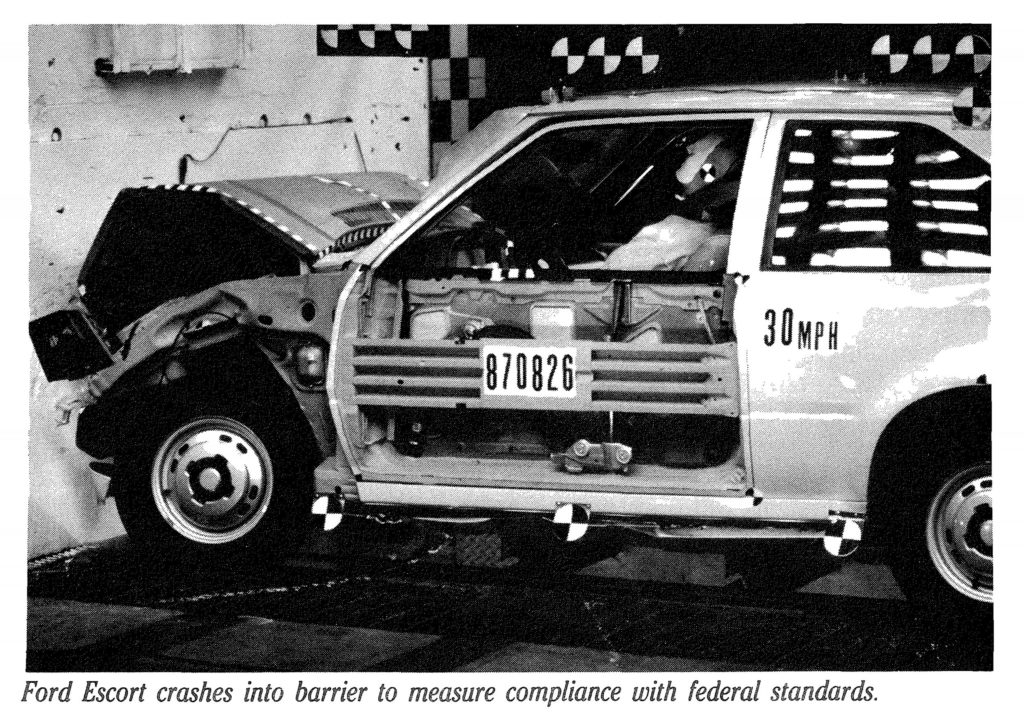

1987 test: 1987 Ford Escort

The IIHS declared “cosmetic” parts to have no safety relevance based on crash testing of individual parts in 1987 and 2000 (and possibly a similar 1995 test done by United Kingdom-based Thatcham; accounts of which parts were removed here vary.)

In 1987, the IIHS ran a 1987 Ford Escort with automatic seat belts through a federal 30 mph full-frontal collision test required for certain FMVSS standards. (The test is less relevant today from a consumer-facing perspective. NHTSA ratings dictate a full-frontal crash test at 35 mph; the IIHS doesn’t test full-frontal anymore in determining its safety ratings.) The fenders, door skins and grille were removed, and an aftermarket hood was installed to test hood intrusion.

As the 1987 Escort “met and far exceeded all federal requirements,” the IIHS effectively declared that all grilles, fenders and door skins are irrelevant for safety on all vehicles. It concluded the unspecified aftermarket hood was also safe, and determined based on inspections (but not crash tests) that other “competitive hoods” had buckle points and ought to “buckle as they should in frontal crashes.”

Zuby said Thursday he wasn’t sure if the results were within normal test variability or, as occurred during Tracy’s test, indicated greater risk but still preserved a passing grade. (As the IIHS variability studies involved its own metrics rather than the FMVSS criteria used in 1987, this might not have been known.)

2000: 1997 Toyota Camry

In 2000, the IIHS ran a 1997 Toyota Camry through its 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test without its fenders, door skins and bumper fasicas and with a CAPA-certified hood.

Ironically, the Camry with OEM parts actually scored worse — “acceptable” rather than “good” in head and neck injuries. Other results were higher on the experimental Camry, but still within the “Good” range and within the kind of variability occurring on production cars.

Again, the IIHS concluded its results applied to all fenders, bumper covers and door skins on every vehicle, calling it illustrative of the “irrelevance of safety in the cosmetic crash parts debate.” (Its case was buoyed by the apparent lousy quality of competitors’ vehicles back then; the Camry missing parts performed better in crash tests than “most competing midsize cars that still have such parts,” the IIHS noted.)

The IIHS in 2000 called hoods the one “cosmetic” part that still “could be a source of safety problems,” (which by definition seems to indicate hoods aren’t “cosmetic,” but whatever) and did not declare all aftermarket hoods to be automatically safe.

However, it suggested all CAPA hoods were safe, writing “CAPA certifies hoods by ensuring that the same buckle points present in hoods from car companies also are present in the aftermarket hoods it approves.”

Then-IIHS President Brian O’Neill also said, “It’s obviously not feasible to crash test every aftermarket hood. But in several tests in which original-equipment hoods have been replaced by aftermarket ones, the replacement hoods have performed exactly as they should. This is to be expected because the buckle points are built in.”

“These tests also have shown that non-OEM hoods copied with the care needed to earn CAPA certification perform similarly to the original equipment in crash tests,” the IIHS wrote Feb. 15.

CAPA’s own testing has found some obvious flaws in uncertified hoods, and Australian aftermarket hood research also raises red flags.

The IIHS doesn’t seem to be making a determination that all cosmetic parts are all of equal quality, merely discussing whether they contribute equally — which is to say not at all, according to the IIHS — to safety.

As the IIHS wrote in 2010, “For things like fenders, grilles, and bumper covers, the issues are mainly cosmetic — fit, finish, and wear. These parts don’t affect vehicle strength in a collision and are irrelevant to crash safety.”

Zuby said the IIHS has found that “for some aftermarket parts, like the cosmetic ones, it probably doesn’t matter (for safety).”

Remove them, and “you get the same results” in a crash test, he said. A fender, for example, was “not carrying any load” and even had slotted holes to be lined up — it wasn’t safety related, according to Zuby.

2010: 2008 Dodge Ram 1500

In 2010, the IIHS put a 2008 Dodge Ram 1500 with a CAPA-certified bumper reinforcement beam through the 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test and a 5 mph frontal test. (Diamond Standard told the Auto Body Repair Network that it made the bumper.)

“Results for both of the pickups were nearly identical,” the IIHS wrote.

Zuby said Thursday he wasn’t sure if the results fell within normal variability, as occurred in 1997, or if they more closely resembled what happened with the Tracy testing — increased risk but still “Good” ratings.

Again, the IIHS appeared to extrapolate the result to every CAPA-certified bumper beam.

“This is what we expected,” then-IIHS President Adrian Lund said in a stateement then. “It shows that aftermarket parts can be reverse-engineered without compromising safety. An aftermarket bumper that meets CAPA’s new standard should perform as well as the original.”

It also stressed the danger of non-CAPA bumper beams based on tests of a 2009 Camry with a bumper beam stronger than the original and a 2005 Ford F-150 beam with larger fog light recesses.

Lund said of the Camry beam: “The aftermarket bumper bar is thicker and heavier than the original. That’s not a good thing from a safety standpoint. Aftermarket bumpers need to perform exactly the same as original bumpers in a crash. Even small changes in design can skew airbag sensors and alter vehicle damage patterns.”

As for the F-150 bumper beam, which ironically posed lower repair costs by protecting foglamps, Lund said: “There’s a difference between reverse-engineering an aftermarket part to the original specifications and re-engineering one. You don’t want to make it better or worse. You want to make it the same.”

The IIHS in 2010 noted that Consumer Reports advised owners not to replace structural parts like bumper beams, and continued, “Consumers are right to be cautious, Lund says, because it’s clear that structural aftermarket parts must be exactly copied to be sure they’ll work properly in a crash.”

The keyword is “exactly copied,” and the IIHS wrote Feb. 15, “Tests conducted by IIHS in 2010 show that structural components can be copied with sufficient fidelity to preserve crashworthiness following repair of a damaged vehicle.”

It also agreed in 2010 there could be a lot of parts that wouldn’t make this cut:

How structural parts are designed and produced can affect crashworthiness because these parts make up the front-end crush zone and safety cage. The crush zone absorbs crash energy, and the safety cage helps protect occupants by limiting intrusion.

Automakers typically use high-strength steel when building the passenger compartment and bumpers. On the other hand, aftermarket suppliers can cut costs by using weaker grade steel or substituting polystyrene foam for the high-impact polypropylene foam automakers use.

In turn, the collision market is a hodgepodge of domestic and overseas suppliers who build structural parts to their own internal guidelines, so there’s no guarantee the parts are equivalent to original equipment in terms of quality and safety.

“When it comes to structural parts, the detail and the quality matter,” Zuby said. “There’s no question.”

The IIHS’s research demonstrated that “this is not an impossible task” to replicate a structural OEM part, he said.

But it has to match the dimensions and qualities of the original precisely, Zuby said.

“If you’re going to source your aftermarket parts from some one other than the OE, you’ve got to make sure that they’re doing as good a job as the OE at producing that part,” Zuby said.

In a separate discussion, he mentioned variables like shape, thickness, material, attachment location and attachment construction could be checked against a baseline part as ways of determining equivalency without crash testing.

Out-of-context for legislatures?

We asked Zuby at one point if the fact that some of the aftermarket parts ordered for the crash testing didn’t fit affected the IIHS assertion that they’re all just as good.

“Our research says they can be as good,” Zuby corrected us. “They aren’t necessarily as good.”

He said that was the problem with the aftermarket parts discussion. One side said all of them were bad, while the other said all of them were good.

“The reality is, some are good and some are bad,” Zuby said.

Despite the IIHS and Zuby’s clear distinctions as to which structural parts are safe and what according to the IIHS is the obvious limitations of extrapolating from a single cluster of parts, aftermarket parts advocates have arguably presented these results as applicable to wider swaths of parts than might be appropriate.

In public comments over Hawaii House Bill 1620 this legislative session, the Hawaii Insurers Council declared, “A November 3, 2010 article published by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) found that like kind and quality (LKQ) bumpers performed similarly to OEM bumpers in a crash test. The article further states that cosmetic parts such as fenders, quarter panels, bumper covers, etc. serve no safety or structural function.”

“The Insurance Institute of Highway and Safety has time and time again — and I will say this is three different decades — have crash tested motor vehicles with aftermarket parts outfitted on these vehicles and have come to the same conclusion — that many of these parts are irrelevant to safety,” LKQ lobbyist Ray Colas told the House Committee on Intrastate Commerce on Jan. 31.

And in discussion of Maryland House Bill 1258, the Property Casualty Insurers Association of America wrote in 2016: “The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) states that aftermarket parts do not compromise the safety of a vehicle.” The link does direct readers to the 1987 testing, but the sentence itself doesn’t clearly qualify that the PCI is only referring to results derived from five missing 1987 Escort parts and an aftermarket hood.

Such comments can be misleading to lawmakers attempting to understand the issue if insurers in that jurisdiction are writing for and vendors selling structural parts like bumper beams, regardless of if they’re certified by CAPA. Structural aftermarket radiator supports, which nobody seems to have crash-tested outside of Tracy, also seem to be for sale and used in at least one estimate.

Asked if the IIHS’ comments being taken out of context, Zuby said, “We definitely have not described our test results as indicating that all aftermarket parts are good.”

Some parts were sub-par, Zuby agreed. “We know those are out there,” he said.

“I think repairers, insurers, people who’re trying to do the right thing have a hard time, given the fact that there is variability in the quality of the parts that are in the supply line,” Zuby said.

We submitted that the IIHS itself only conducted a few tests, and for example, based on one 2010 test didn’t truly know that all CAPA-certified bumpers were equivalent to one another.

Without endorsing any specific certification programs, Zuby suggested some form of independent, point-by-point comparison of parts might be in order.

More information:

“OEM vs. aftermarket parts and Honda Fit crash tests”

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Feb. 15, 2018

“Test Shows Cosmetic Parts Do Not Affect Safety Compliance”

IIHS Status Report, Nov. 21, 1987

“Cosmetic repair parts are irrelevant to safety”

IIHS Status Report, Feb. 19, 2000

“Unlike other parts used in auto repairs, hoods could influence safety”

IIHS Status Report, Feb. 19, 2000

“Aftermarket bumpers meeting new standard perform well in crashes”

IIHS Status Report, Nov. 3, 2010

Images:

In 2010, the IIHS put a 2008 Dodge Ram 1500 with a CAPA-certified bumper reinforcement beam, pictured, through the 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test and a 5 mph frontal test. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

A 2013 Honda Fit received a moderate-overlap crash test while sporting imitation components included Certified Automotive Parts Association-certified fenders and a CAPA-certified hood; a NSF-certified bumper reinforcement beam; an uncertified aftermarket radiator support, windshield and drivers-side front wheel; and two uncertified aftermarket hood hinges, according to experiment contributor Burl’s Collision. (Provided by Tracy Law Firm)

In 1987, the IIHS ran a 1987 Ford Escort with automatic seat belts through a federal 30 mph full-frontal collision test required for certain FMVSS standards. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

In 2000, the IIHS ran a 1997 Toyota Camry through its 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test without its fenders, door skins and bumper fasicas and with a CAPA-certified hood. Ironically, the Camry with OEM parts actually scored worse — “Acceptable” rather than “Good” in head and neck injuries. Other results were higher on the experimental Camry, but still within the “Good” range and within the kind of variability occurring on production cars. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

In 2000, the IIHS ran a 1997 Toyota Camry through its 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test without its fenders, door skins and bumper fasicas and with a CAPA-certified hood. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

In 2010, the IIHS put a 2008 Dodge Ram 1500 with a CAPA-certified bumper reinforcement beam and a factory version through the 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test and a 5 mph frontal test. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

A 2009 Camry with an aftermarket bumper beam stronger than the original was problematic, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety said in 2010. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)