IIHS discusses airbag delay seen in Tracy’s crash test of aftermarket-parts Honda Fit

By onBusiness Practices | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

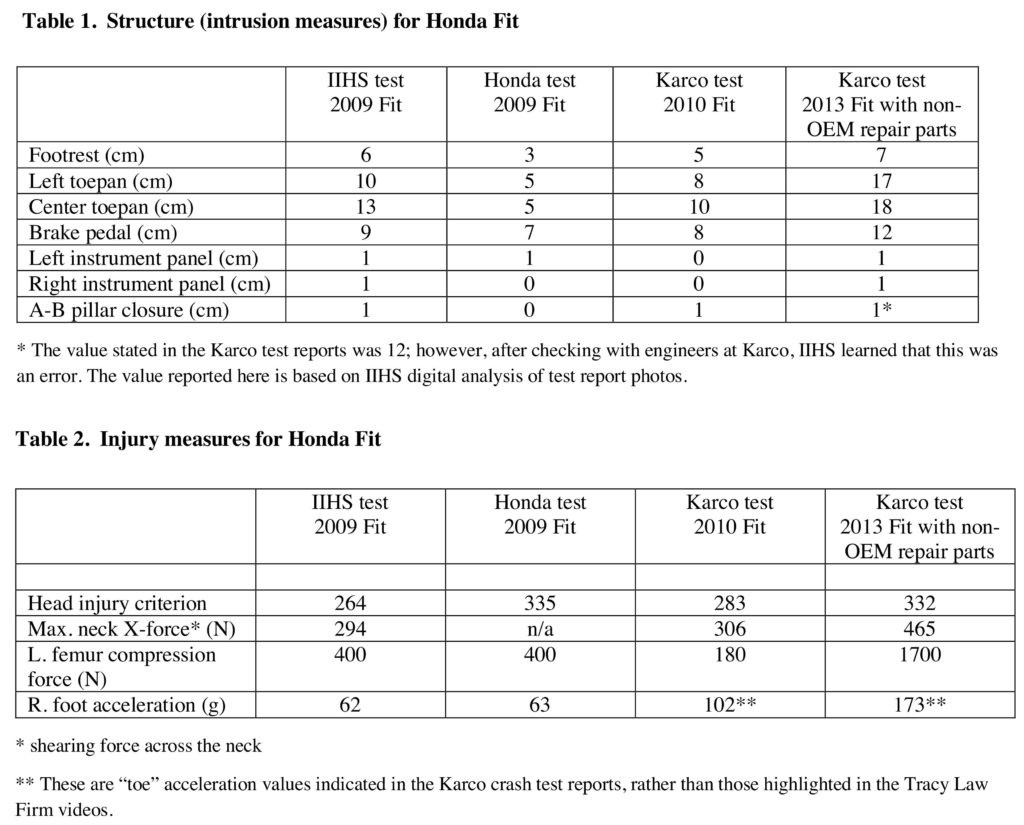

A lack of context as to what constitutes “normal” results has prevented the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety from analyzing some of the findings that seemed to support attorney Todd Tracy’s criticism related to a crash-tested 2013 Honda Fit bearing multiple aftermarket parts.

IIHS Chief Research Officer David Zuby explained that in some cases, the IIHS lacked data to determine if the differences were part of the normal variability unaltered cars naturally show during crash testing.

And while Tracy tested a Fit with both driver and passenger dummies in the 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test, the IIHS typically only wrecks cars with a “driver” inside. Zuby said that the threat to the passenger is “relatively benign” compared to the risk to the driver.

Tracy had written in response to the IIHS’ Feb. 15 advisory:

The IIHS Advisory proved our hypothesis that aftermarket parts and non-oem approved repair methods do not perform the same as OEM parts.

Specifically, the tests proved that aftermarket and non-approved oem repair methods altered the following:

More structural collapse in footwell area

More structural collapse in area underneath the occupants

Altered occupant kinematics

Altered seatbelt restraint system performance

Altered the airbag restraint system performance

Increased the energy

Increased the injury values to the head, neck, femurs and ankles

IIHS admits that some of the differences between the vehicles appear large

IIHS admits that the tests prove an increased risk of injury

If the aftermarket parts and the non-approved repair methods performed the same as OEM, the data plots, injury values, and performance values should be identical. They aren’t. That’s because the OEM develop and design its vehicles with OEM not aftermarket or non-approved repair methods.

Side airbags

We observed a side airbag blowing about 11 milliseconds later on the aftermarket Fit’s 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test than it did on a control 2010 Honda Fit subjected to the same test.

The steering-wheel airbag begins to blow about a frame/millisecond before the OEM edition, but the passenger dash airbag seems almost perfectly in sync.

Zuby said the driver’s front airbag deployment time was within the normal range of variability observed during IIHS testing of unaltered vehicles.

As for the side airbag, Zuby said he couldn’t tell if the delay was outside normal parameters because the IIHS’ research on normal testing variability occurred before side airbags were common.

“We can’t comment on the side curtain,” he said.

However, Zuby went on to offer an interesting point about frontal airbag timing, one which he thought applied to side airbag timing as well.

“Because one is later doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s offering less protection,” Zuby said. “It may be adjusting to the difference between the crash tests.”

Honda has famously pointed out what a few hundredths of a second in airbag timing can mean.

But Zuby explained that a delay might at times also be the result of the vehicle sensing and adapting to the conditions of the crash.

For example, if a particular vehicle is decelerating at a slower rate during a crash due to the unique circumstances of the impact, “you don’t want the airbag to come out at the same time as in a crash where it slows down more quickly.”

Otherwise, the airbag might lack sufficient pressure when the occupant makes contact with it.

“You can’t just say, ‘Because it’s late, it’s bad,’ or ‘Because it’s early, its bad.'”

At a certain point, an airbag deployment time difference becomes unacceptable, Zuby said.

“If you get huge differences in deployment times so that you see the dummy hitting his head against something before the airbag deploys, that’s a problem,” Zuby said. At a few milliseconds, however, “it’s harder to say that one is right and one is wrong.”

‘Pass-through’

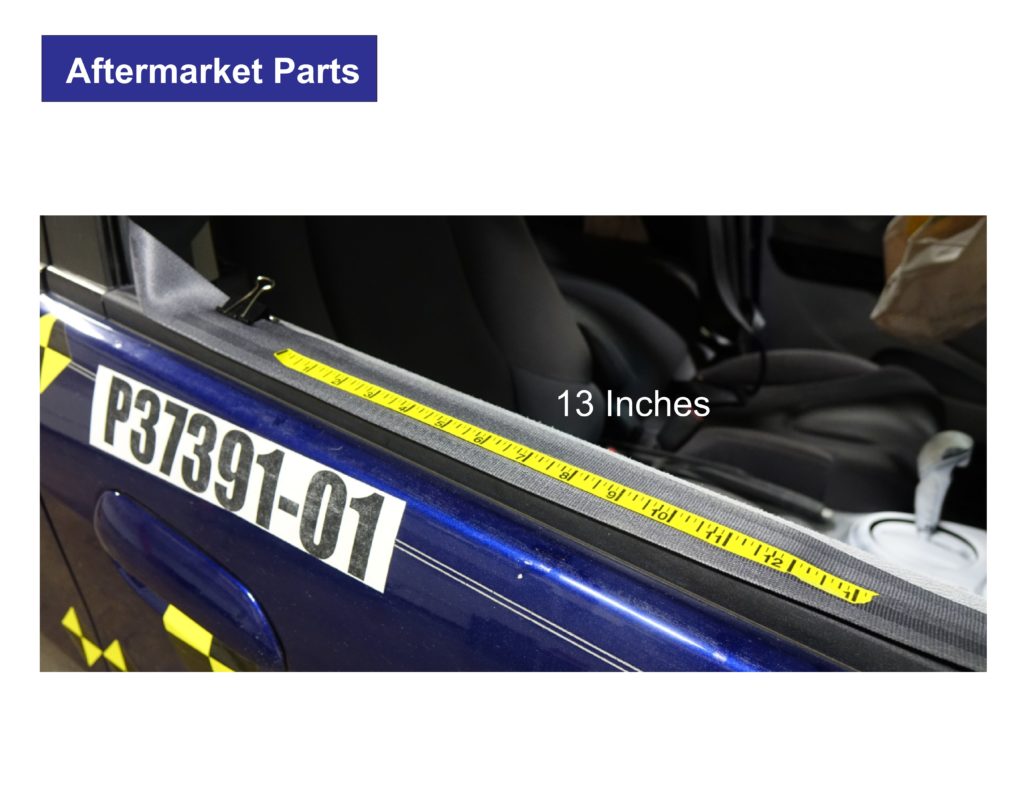

Tracy has highlighted what he described as an excessively high “pass-through” — the length of seatbelt passing through the D-ring as the crash impact hurls the occupant forward before being halted by the airbag.

The control black 2010 Honda Fit posted 8 inches of passenger-side seatbelt pass-through. Tracy described that “baseline” measurement as similar to the one found by the IIHS’ identical crash test of a 2009 Fit years ago.

A red 2009 Honda Fit, which received Honda-unapproved repairs including a glued roof (Honda demands welds) and an aftermarket windshield (Honda doesn’t recommend imitation parts), registered 12 inches of pass-through after another identical crash test.

“What does that do to the human body?” Tracy asked in a January video, explaining that it affects “kinematics” — how the occupant moves forward and backwards to and from the airbag, respectively. It also can affect the Head Injury Criterion — your brain’s ability to withstand crash forces without injury, according to Tracy — by having excessive airbag engagement send the occupant’s head striking a different part of the head restraint, he said.

The blue 2013 Fit with multiple aftermarket parts “actually allowed 13 inches of pass-through to go over,” Tracy said. That affects the HIC, as “you end up missing almost the entire head restraint,” Tracy said. Footage shows the head of the aftermarket-parts passenger striking the head restraint and lolling around the side of it.

Tracy said the crash tests prove “when you change the assembly … and when you alter the material of the vehicle, than that has devastating consequences to the restraint system performance” seen on the seatbelts.

Zuby said the IIHS did study pass-through, but “I don’t think our repeatability study looked at that.”

“Small differences” wouldn’t be cause for concern, but larger ones would, Zuby said, though he noted this might reflect a difference in test setup.

Neck X-force

Tracy’s data demonstrates a maximum neck X-force for the driver that came in around 165 Newtons higher than the control Fit and the IIHS’ own.

Zuby said that the IIHS again here didn’t have a variability range against which to compare the data.

The testing organization collects data on X-force, but it then converts it and other measurements into a “neck injury index” it uses instead. The IIHS’ variability study doesn’t look at the statistic by itself.

What Tracy had discussed was “not the way we normally evaluate neck force,” Zuby said.

Without going back to the original data tapes, he couldn’t compare neck X-force, Zuby said.

More information:

“OEM vs. aftermarket parts and Honda Fit crash tests”

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Feb. 15, 2018

Todd Tracy Honda Fit crash testing results

Images:

A Dec. 19, 2017, test at Karco crashed a 2013 Honda Fit into a 40 percent moderate-offset barrier at 40 mph. The Fit was carrying multiple aftermarket parts. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)

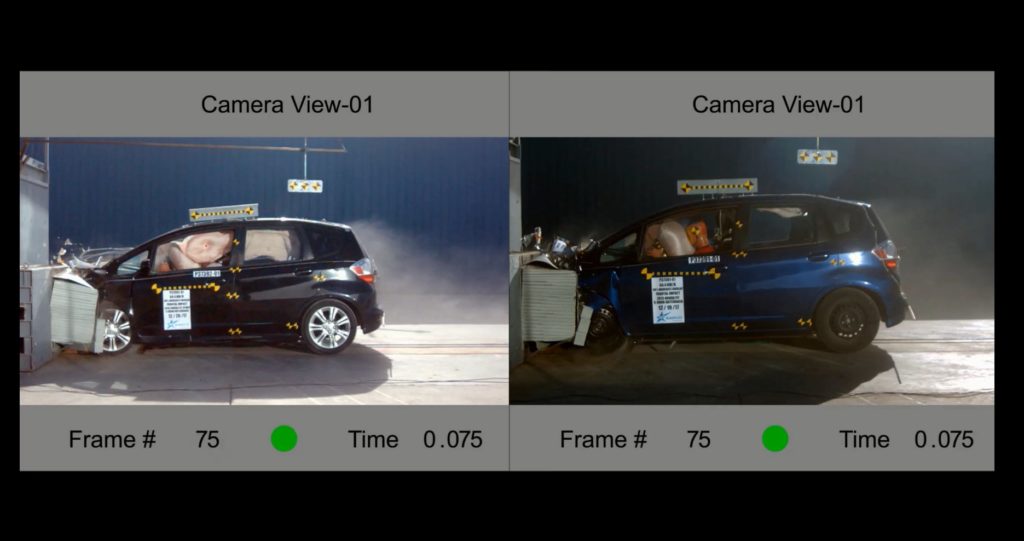

A 2013 blue Honda Fit with aftermarket parts, right, doesn’t manage to blow its side-curtain airbag until about 11 milliseconds after the deployment on the control black 2010 Fit. (Screenshot from Karco video provided by Tracy Law Firm)

Todd Tracy of the Tracy Law Firm said that a 2013 Honda Fit with multiple aftermarket parts saw higher passenger-side seatbelt “pass-through” measurements than a control Honda Fit from the same 2009-13 design generation after a 40 mph moderate-overlap crash test. (Provided by Tracy Law Firm)

An Insurance Institute for Highway Safety analysis of attorney Todd Tracy’s data concluded that a 2013 Honda Fit crash-tested with numerous aftermarket parts would still have achieved “Good” moderate-overlap ratings. However, it acknowledged that some measurements fell outside the normal range of test variability and indicated increased risk of injuries, even if the overall results fell within the “Good” threshold. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)