Chipotle CFO shows auto body shops delivering quality can deliver strong balance sheet

By onAssociations | Business Practices | Education | Market Trends | Repair Operations

Chipotle Chief Financial Officer Jack Hartung sometimes speaks to business schools about the company, which buys higher-quality ingredients at a higher expense, charges about the same as other fast-casual competitors and makes high returns.

Often, a professor will say, “‘You can’t have those three things go together,'” according to Hartung. One of these items — investing in quality, charging the same, or making acceptable returns — simply has to be sacrificed, they reason.

But Chipotle decided “we need to have all three,” Hartung said. It accomplished this by looking for solutions besides the easy crutch of sacrificing quality and violating the company’s philosophy of “Food With Integrity.”

Chipotle’s story, told Wednesday at the Society of Collision Repair Specialists’ Repairer Roundtable, offers lessons for the collision repair industry. Like Chipotle’s own sector, the auto body repair industry can find it far too easy to take the shortcut of sacrificing quality to preserve the other two factors — and contribute to a conventional wisdom that such behavior is the only way to survive.

Hartung told the audience of repairers that another way was possible. It involved tailoring a business model to the vision you sought to accomplish.

In Chipotle’s case, founder Steve Ells decided he could take what he learned from the fine dining sector and apply it to a taqueria, according to Hartung. Everyone told him that he was wrong, that no one cared if he toasted cumin or dispensed oregano flakes by hand instead of shaking it out of a spice jar.

“He didn’t care,” Hartung said. Ells wanted to sell people food he could be proud of, a stance that also led to the company using free-range pork without growth hormones or antibiotics around 2000 after he learned how delicious such meat was, according to Hartung.

At the time, such considerations hadn’t entered the public consciousness, according to Hartung. “I didn’t know that stuff growing up,” he said. He said he even worked at McDonalds before Chipotle and had no idea about the state of animals used in food.

Chipotle sought to educate customers about the difference, including with an emotional advertisement that resonated with existing customers and those who’d never been to one, according to Hartung.

Hartung said the company wanted to encourage people to think about what was in their food and ask questions, figuring that the more educated customers were, the better it was for Chipotle. Otherwise, customers might just assume the restaurant was identical to competitors.

“The food that we buy is very expensive,” Hartung said.

Sometimes, Chipotle had no choice but to pass costs on to consumers, according to Hartung. “Every now and then, we do have to raise prices,” Hartung said.

But rather than gradually increasing prices each year as was typical, “we don’t nickel and dime the customers,” he said. The company’s history of price increases sees a few years between each one, according to Hartung.

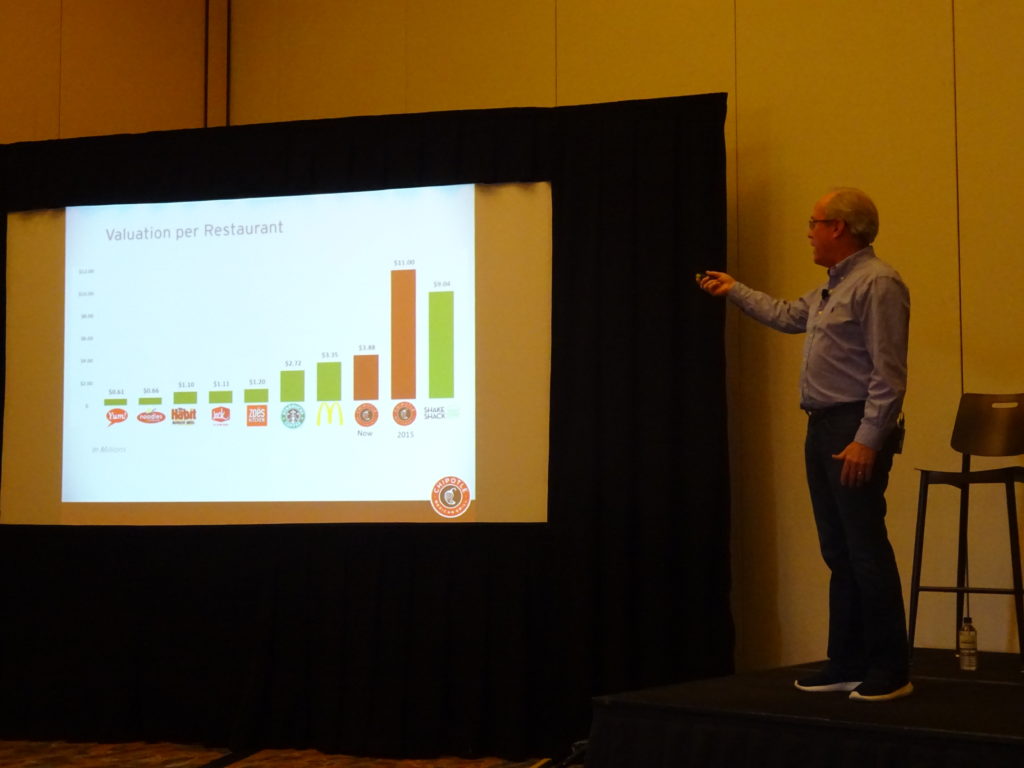

The company has proven the professors wrong. Chipotle’s stock opened in January 2006 at $42.20 and was trading around $330 per share, according to Hartung and Yahoo Finance. Its 2017 revenue was $4.5 billion, with net income of $176.3 million, and it ended the year with 2,408 restaurants — compared to just one location 25 years ago.

Hartung said Chipotle spends about $750,000-$800,000 on a new location, but the new restaurant can do $2 million in sales once it reaches its run rate. The cash-t0-cash return on investment is 45-50 percent, “which is really quite good” in the industry, according to Hartung.

Even after its 2015-17 food safety headaches cut their worth from $11 million at the peak (on an $800,000 investment, remember!), Chipotle’s restaurants are still valued at $4 million each, according to Hartung. It has higher returns than many of its rivals even after losing 15-20 percent of customers during its difficulties. he said.

Rather than go the “whole paycheck” model of Whole Foods and charge customers more than fast-casual rivals like Panera, Moe’s and Qdoba, Chipotle looked for efficiencies in line items other than food to help achieve the trifecta the professors called impossible.

That flies against the conventional restaurant thinking, which involves attempting to engineer savings out of the supply chain, according to Hartung.

“They try to squeeze it,” he said.

Instead, Chipotle made restaurants smaller to save money and spent less on advertising. The company felt that food itself would matter most to customers, and marketing “can’t substitute for an extraordinary experience,” he said. That’s how word of mouth happens, he said.

The company increased marketing for the past two years during its food safety image issues, but it would likely scale it back, Hartung said.

Society of Collision Repair Specialists board member Matthew McDonnell (Big Sky Collision Network) said Chipotle didn’t have to buy cheap meat, and “we don’t have to do those things either” and compromise on quality in the collision repair industry.

He said he felt shops played the “victim card” often, and the moment they broke themselves from the chain of “‘we’re forced to'” do something delivers freedom. He said it was “very exciting” to see an example like Chipotle which had done that.

“We don’t have to (compromise),” McDonnell said.

Hartung said sometimes such a position meant taking a “tough stand.” About four years ago, the company found a pork supplier hadn’t been delivering the criteria promised. Confronted by this, the supplier’s answer was “‘We don’t really want to fix them,'” and “‘we think your protocols are wrong.'”

All the pork was safe and delicious, but Chipotle fired them on the spot and donated the meat rather than compromise on its principles — even though the company lost revenue from the loss of 25-30 percent of its pork supply. (It ended up coping by instituting a rolling blackout system where restaurants took turns being porkless.)

The media and customers “applauded that move,” Hartung said.

Rather than a shop owner acquiescing to an insurer, “maybe I’m starting a food fight,” refusing to compromise on quality — and drawing positive attention, he said. Compromising on things like safety and parts could be a “slippery slope,” he said.

Images:

Chipotle Chief Financial Officer Jack Hartung discussed how the company managed to deliver strong returns without skimping on quality during the Society of Collision Repair Specialists Repairer Roundtable on April 11, 2018. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)

Chipotle Chief Financial Officer Jack Hartung discussed how the company managed to deliver strong returns without skimping on quality during the Society of Collision Repair Specialists Repairer Roundtable on April 11, 2018. Hartung presented the company’s results prior to its food safety issues between 2015-17 too. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)