Luehr, Kuehn: Grabbing every set of keys might not be best tactic for auto body shop

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Repair Operations

It might seem counterintuitive, but a collision repairer grabbing every set of keys they can might not be the best business plan, two consultants said last fall. It’s something to consider as your shop grinds through the winter and the inevitable flood of vehicles.

Elite Body Shop Solutions CEO Dave Luehr said on an October 2018 webinar that he was “passionate” about scheduling. He called it often the starting point when he provides shop consulting services, for “no other process” he could teach would work in an environment with too many vehicles. The best blueprinting efforts fail because they don’t understand scheduling and optimum work in process (WIP), according to Luehr.

A poll of the audience of nearly 200 people on the webinar found 59 percent of respondents schedule by counting estimated labor hours, 22 percent tying it to the number of vehicles, and 10 percent admitting to “‘winging it.'”

Luehr said he understood the “grab the keys” mindset when things are slow. But don’t let the exception become the rule if your shop gets busy again, he said.

“We can be very reactive,” said co-presenter Ron Kuehn, president of Collision Business Solutions and the source Luehr credited for any scheduling tips he taught.

Kuehn said shops feel less “antsy” with a certain buffer of work, calling such owners “WIPaholics.” They have a tendency to completely shut down intake when they get overwhelmed, restarting the spigot of work later.

The problem with grab-the-keys is that it runs into the reality of your shop’s capabilities, based upon the webinar. Luehr directed shops to Little’s Law, which can serve as an equation for cycle time, and illustrated it with the following example he said he took from Rich Altieri of Auto Body Management Solutions:

Work in process

Say a shop with 10 cars in its production system on average delivers two a day. If 10 customers suddenly show up and bring the car’s workload to 20 vehicles, it still only can deliver only two cars a day.

The 10-car shop has a 5-day cycle time, while the 20-car shop has a 10-day cycle time, Luehr said. Cycle time is work in process divided by the average number of cars delivered daily. A seven-day cycle outputting four cars a day would give the repairer an optimum WIP count of 28 vehicles, he said.

A repairer has to develop their optimum work in process, according to Kuehn. “Just having a system is not gonna fix your problem,” he said.

Luehr said he will be asked by a shop why its cycle time is so poor. They blame insurers, “of course,” or technicians, but the biggest factor really is just too much work on the property, he said.

Excess inventory (WIP) also can contribute to poor cash flow, wasted resources and chaos, according to the webinar. Repairers look at their profit and loss report and see they’re ostensibly making money — yet have no cash, Luehr said.

A repairer has money (for example, parts orders) and administration tied up in every vehicle on the facility, according to Kuehn. If you are efficient as a business, you can turn over dollars multiple times before the bills come due, Kuehn said.

Scheduling was also hindered by a repairer basing it on incorrect data, according to Luehr and Kuehn. Kuehn described repairers scheduling using projected work hours — but based upon an estimate written at the curb. When supplements arise, “that can constipate the car” as much as other factors, he said.

A situation could arise where what was projected as a $1,500 job in a curbside estimate was really $2,000 once the repairer filed a supplement, said Kuehn, who used the term “swell” to refer to such inflation. That particular “swell” saw the job grow by 25 percent, and that sort of thing could leave a shop with more work than it could handle, according to Kuehn.

In this vein, Kuehn advised against scheduling for the exact amount the shop needs to do that day, giving the example of scheduling the $7,000 in sales a hypothetical shop needed daily. Instead, look at what the facility started and ended with.

Luehr also encouraged shops not to be too aggressive with their goals at first, citing the production system’s status as a reason. He said he would recommend starting by, for example, knocking a 10-day cycle time down to eight or nine days.

The presentation included another example using dollars. An $8,000 daily output with a seven-day cycle goal worked out to $56,000 of work in process.

Kuehn called the process “a daily discipline” and suggested setting a 20-day goal (which would be a month’s typical four 5-day work weeks) and dividing it by 20 to get the daily goal.

In a perfect world, a shop might output 20 vehicles a week and bring in 20 vehicles a week for optimum profitability, Luehr said.

The daily goal won’t change even though the month’s goal changes, according to Kuehn. He gave the example of a shop’s financials for September — it might have lost money, for the month only had 19 working days and a paid vacation day.

Luehr said he thinks of scheduling like a dial. A shop with an optimum work in process of 20 vehicles a month needs to keep the dial at that level. Let the amount climb too high, and the scheduler “blew up the nuclear power plant,” he said.

Severity

Luehr said “that madness” of creating unstable work and ramming it through a shop needed to stop. Repairers had to pull the right mix of work to feed their production system.

Kuehn told shops not to schedule for “what shows up at the door” but instead for “how backed up you are.” It didn’t matter when all the work came in. It’s all about what a repairer could finish, he said.

One option would be to have a tapered scheduling system, with what would be six vehicles accepted Monday shrinking to two on Friday, according to Luehr. It’s not optimal — what if you get five easy bumper repairs on Monday? — but it was better than nothing, according to Luehr.

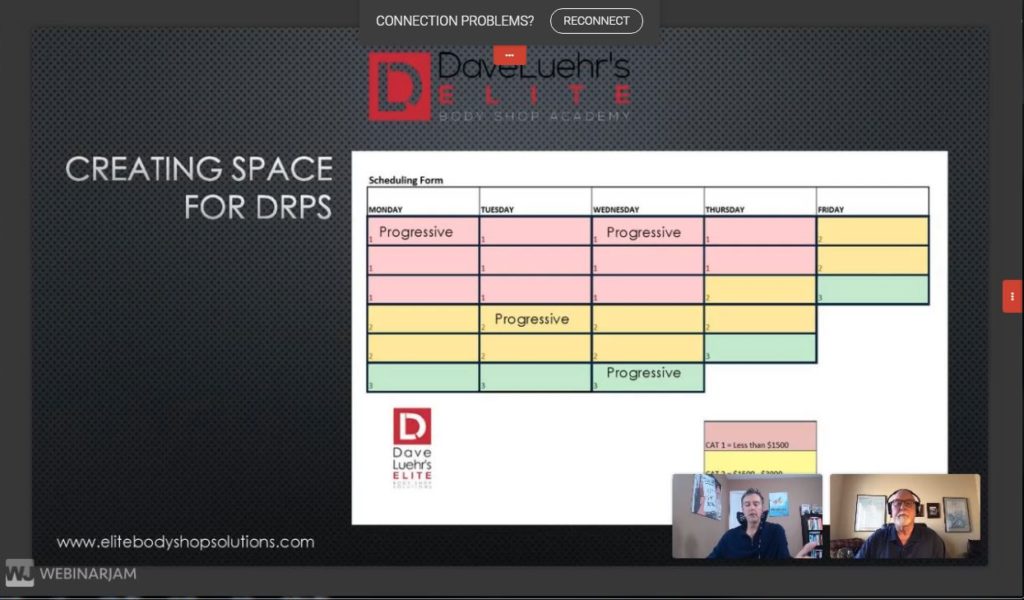

Luehr said he instead likes to triage based upon severity, with a “CAT 1” being a $0-$1,499 repair, a CAT 2 from $1,500-$3,999 and CAT 3 anything $4,000 or more. He called it a “very stable” system he’s used since 2010. Kuehn said he found that repairers were better able to gauge a dollar amount than labor hours when eyeballing a vehicle.

Kuehn said a repairer could grab a year’s worth of data from their management system, examine their output over the past year (which would take into account the winter), and break it down by dollar categories.

Luehr said it really can be as simple as filling up a chart reflecting different job sizes. If there’s no slots for the type of work left, then don’t have the customer bring the vehicle in.

“You don’t force-feed it,” Kuehn said. If most unscheduled dropoffs come in Monday, then schedule smaller jobs for Wednesday so you can get them out in time. Or block off Monday and “prepare for that”; worst case, you can always call another customer to bring in a vehicle earler, he said.

What about DRP shops? Luehr said that while a shop didn’t know for certain how many vehicles the insurer would deliver, data from the management system could provide a ballpark figure. He gave the example of leaving four slots during a week for Progressive vehicles.

Asked if, say, a CAT 3 could be placed into the spot of three CAT 1s, Kuehn said a shop needed to break down the work into an optimum mix. You cold do such a thing, though he cautioned about bringing in too many small jobs to fill in one’s schedule.

Kuehn at another point observed that small jobs can still require a lot of time and “constipate” a shop. He said that’s why what should be a 5-6 hour repair can take three days to move through the shop.

He also warned the audience about pushing to collect driveable work when there are too many nondriveable vehicles onsite, calling it the “kiss of death” for profitability and satisfaction.

What about getting tow-ins from a DRP insurer who doesn’t cover rentals? “It’s a balance,” Kuehn said. Scheduling is not an “exact science,” and not all your problems will be solved, but don’t resign yourself to the idea that everything is dictated and the shop just can’t improve, he said.

For more on scheduling, shops can also check out this 2016 Mike Anderson webinar, one of the Collision Industry Electronic Commerce Association’s “CIECAsts” that year:

More information:

“Are You Running Your Schedule OR Is Your Schedule Running YOU (Ragged)?”

Dave Luehr’s Elite Body Shop Academy, October 2018

“Little’s Law” on Corporate Finance Institute website

“Little’s Law” chapter by John D.C. Little and Stephen C. Graves

Building Intuition: Insights From Basic Operations Management Models and Principles, 2008

“2016 04 18 CIECAst Scheduling and Best Practices”

CIECA YouTube channel, April 18, 2016

Images:

Just grabbing the keys of every customer can lead to bad cycle times and cash flow, according to a 2018 Dave Luehr’s Elite Body Shop Academy webinar. (diego_cervo/iStock)

Elite Body Shop Solutions CEO Dave Luehr illustrated work in process in October 2018 with two funnels. Regardless of whether the hypothetical body shop has a workload of 10 vehicles or 20, it can only finish two a day. (Olivier Le Moal/iStock)

This screenshot from an October 2018 Dave Luehr’s Elite Body Shop Academy webinar depicts a scheduling system based upon severity, with blocks reserved for the shops direct repair program insurer. Presenters Dave Luehr, left, and Ron Kuehn, president of Collision Business Solutions, are at bottom. (Screenshot from Dave Luehr’s Elite Body Shop Academy)