COVID-19 tips: Cleaning, dilution with air, disinfecting following directions

By onAnnouncements | Associations | Business Practices | Education | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

One of the main takeaways from this week’s SCRS webinar on cleaning and disinfecting vehicles involved advice repairers should find familiar: Don’t deviate from the instructions validated to have worked.

Essentially, follow the disinfectant manufacturer’s “OEM procedures” when attempting to reduce a vehicle’s risk of COVID-19 coronavirus.

The webinar also saw restoration experts Kris Rzesnoski and Norris Gearhart recommending reducing the potential viral load with airflow and removing soil like dirt or food crumbs from a vehicle.

Follow the validated procedures

The repairer should be using products on the Environmental Protection Agency’s “List N” recommended by the CDC for COVID-19, according to Rzesnoski, a vice president of business development at Encircle. Otherwise, the business “might as well grab water and soap,” he warned.

Gearhart, the founder of Gearhart and Associates, said a repairer could look up a product’s EPA registration, which explains how to to use it.

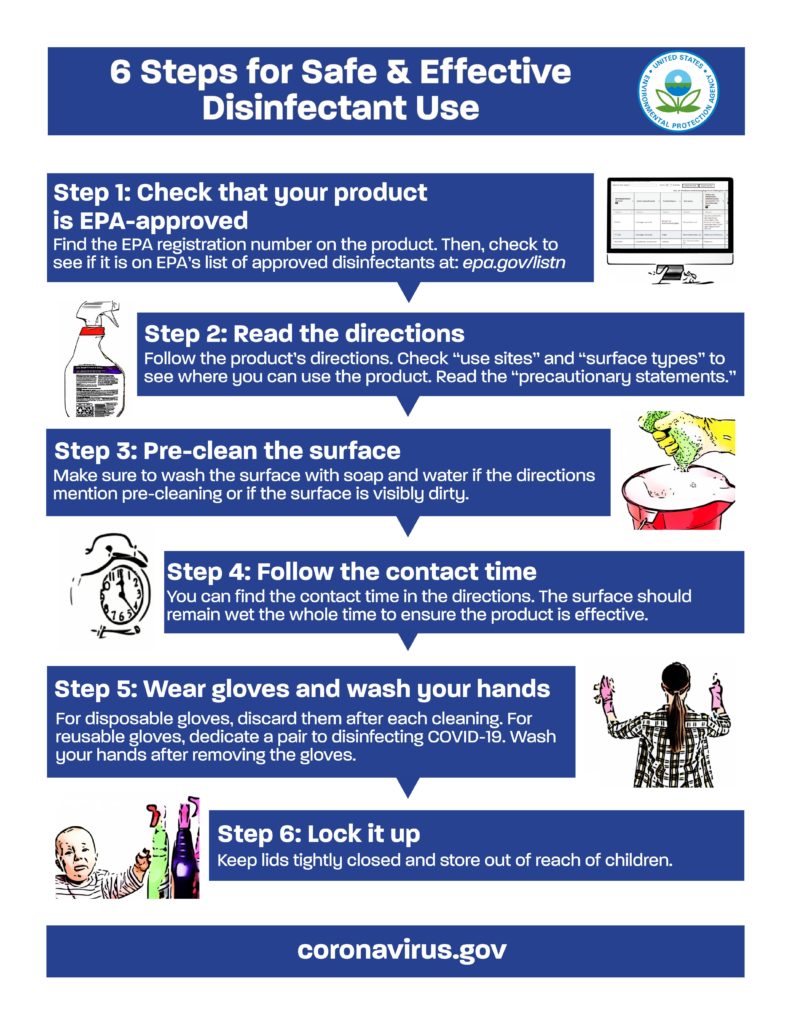

“When using an EPA-registered disinfectant, follow the label directions for safe, effective use. Make sure to follow the contact time, which is the amount of time the surface should be visibly wet, listed in the table below. Read our infographic on how to use these products,” the EPA states on its “List N.”

Gearhart said instructions for materials on EPA’s “List N” will explain how long a surface wiped must stay wet to deliver the claimed reduction of virus. These parameters must be followed, he said — noting it can be difficult to achieve sometimes. It can be hard to keep a surface wet with the disinfectant for the 10 minutes required, he said. You can get “fish eyes” and incomplete drying.

The mechanical action of wiping a surface is “great”; it removes much of the virus, Gearhart said. However, repeated wiping might cause cross-contamination, similar to how methylene chloride paint stripper’s efficiency is halved with each wipe, he said.

Instead, a repairer might be tasked to make a single pass with a wipe and let the substance work from there, based on Gearhart’s comments. As he said, you have to follow the directions proven to deliver the performance associated with the product.

Gearhart also told repairers how to interpret results. If a cleaner declares it kills 99.9 percent of bacteria, it’s a log reduction. If a million virus particles exist on a surface, there might be 1,000 left, he said.

“That’s if you do it right,” he said.

The idea of manufacturer instructions also arose as Gearhart warned about claims that a business could put any substance they wished in a fogger.

Such products were tested with specific delivery methods, according to Gearhart. Using an unvalidated method could produce “drastically different” results, he said. Delivering a substance in an alternative way might change the droplet size or even the electrical charge, he said.

“It may not work the way it was supposed to,” he said.

In this vein, you can’t just expect that applying a disinfectant with a paint gun will achieve the desired result, according to Gearhart. Apply a disinfectant with the method that had been validated, he said.

Disinfecting products aren’t guaranteed to work on porous, soft surfaces like fabric and leather, according to Encircle business development Vice President Kris Rzesnoski and Gearhart and Associates founder Norris Gearhart.

Gearhart said soap and water or hot water steam extraction would be the best options for cloth. Some disinfectants might be more successful if the leather is less porous, “but there’s no guarantees.”

Repairers will need to evaluate substances for compatibility with a vehicle before using them, according to Rzesnoski. (For example, here’s Ford and Toyota‘s guidance on what they would like used.)

For example, he said alcohol-based cleaners can “absolutely decimate the finishes.” Other times, such products might be recommended. On the whole, surfaces were more likely to tolerate a water-based and pH-neutral substance from the N List, according to Rzesnoski.

It’s possible a repairer’s regular distributor doesn’t stock suitable products, which might require a shop to look at the janitorial supply world, he said.

A cleaner that works on one vehicle might be unsuitable for a higher-end vehicle with more sensitive surfaces — and an even higher-end vehicle might require a third product, according to Rzesnoski. He said more expensive vehicles’ natural finishes would demand the “least amount” of invasive actions.

Streamline your product selection as much as possible, according to Rzesnoski. If you use five different products, that means you’ll need five different processes, he warned.

“You want to simplify this as easy as you can,” he said.

Airflow

Rzesnoski also encouraged diluting the virus by opening the vehicle windows and doors and blowing the organic virus load away. Then apply a water-based and pH-neutral disinfectant — qualities less likely to harm a vehicle surface — from the N List. He said he would still let the vehicle sit a day or two longer, with that duration dependent on the treatment applied before.

Gearhart said such dilution shouldn’t be done in the shop next to other vehicles. Rzesnoski recalled how he used to disinfect law enforcement vehicles outside, blowing the air out into an unoccupied space.

The National Institutes of Health on March 17 announced that research it had done alongside the Centers for Disease Control, UCLA and Princeton examined the length of time COVID-19 can live on various surfaces.

“The scientists found that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was detectable in aerosols for up to three hours, up to four hours on copper, up to 24 hours on cardboard and up to two to three days on plastic and stainless steel,” NIH wrote about the research published in the New England Journal of Medicine. “The results provide key information about the stability of SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19 disease, and suggests that people may acquire the virus through the air and after touching contaminated objects.”

However, while the virus could still be detected, not as much of it was left. The article put the half-life of the virus at 1.1 hours as an aerosol, 3.5 hours on cardboard, 5.6 hours on stainless steel and 6.8 hours on plastic, though the authors cautioned that the cardboard data is “noisier” and the results should be approached with caution.

A study published in the Lancet April 2 studied virus life on various surfaces at room temperature (22 Celsius, 71.6 Fahrenheit) and 65 percent humidity, though they cautioned their method for detecting the virus “does not necessarily reflect the potential to pick up the virus from casual contact.”

“No infectious virus could be recovered from printing and tissue papers after a 3-hour incubation, whereas no infectious virus could be detected from treated wood and cloth on day 2,” the Lancet study found. “By contrast, SARS-CoV-2 was more stable on smooth surfaces. No infectious virus could be detected from treated smooth surfaces on day 4 (glass and banknote) or day 7 (stainless steel and plastic). Strikingly, a detectable level of infectious virus could still be present on the outer layer of a surgical mask on day 7 (∼0·1% of the original inoculum).”

Clean the car

Repairers who use the dilution-through-airflow approach musn’t disturb and aerosolize viral loads like those potentially found on floor mats, Rzesnoski said.

Shops should use a HEPA vacuum to clean such surfaces, he said, warning that even a Shop-Vac with a HEPA filter might not be adequate.

“I would really encourage a HEPA vac” rather than a traditional Shop-Vac, Gearhart agreed. It’s more expensive, but it means particulate won’t be resuspended in the device’s exhaust, he said. A traditional vacuum might collect large debris but behave “more like a leafblower” for smaller particles invisible to the naked eye, according to Gearhart.

Gearhart said repairers should also clean and wipe down equipment like the HEPA vacuum nozzle with disinfectant between uses.

Asked if the customer should be told to clean out the vehicle before dropping it off, Gearhart said, “In my opinion, yes.”

The CDC advises cleaning a surface before disinfecting it.

Gearhart said a “really filthy car” is “a giant petri dish on a good day.” Soil like food and dirt could potentially extend the viability of COVID-19, he said.

European Motor Car Works owner Kye Yeung, another participant on the webinar, said his shop tells customers to bring in vehicles “as spartan as possible.” He said he thought customers were aware of the sensitivity of the COVID-19 issue.

Rzesnoski supported reducing organic load — even having the customer clean mats themselves at a car wash to reduce the risk to a business’ team. (One hopes the car wash has a true HEPA vacuum then.) However, the customer shouldn’t be permitted to use the shop’s tools for such a cleaning, he advised. “Let the risk go somewhere else,” he said.

More information:

“Ask the Experts – How Professional Restorers Deal with “Disinfecting” Vehicles”

Society of Collision Repair Specialists, April 28, 2020

Centers for Disease Control, April 29, 2020

CDC interim COVID-19 guidance for businesses

CDC guidance for businesses with suspected/confirmed COVID-19 cases

Centers for Disease Control COVID-19 coronavirus portal

Environment Protection Agency “List N” of COVID-19 disinfectants

Images:

One of the main takeaways from this week’s SCRS webinar on cleaning and disinfecting vehicles involved advice repairers should find familiar: Don’t deviate from the instructions validated to have worked. (Joanna Skoczen/iStock)

Environmental Protection Agency instructions on using “N List” products. (Provided by EPA)

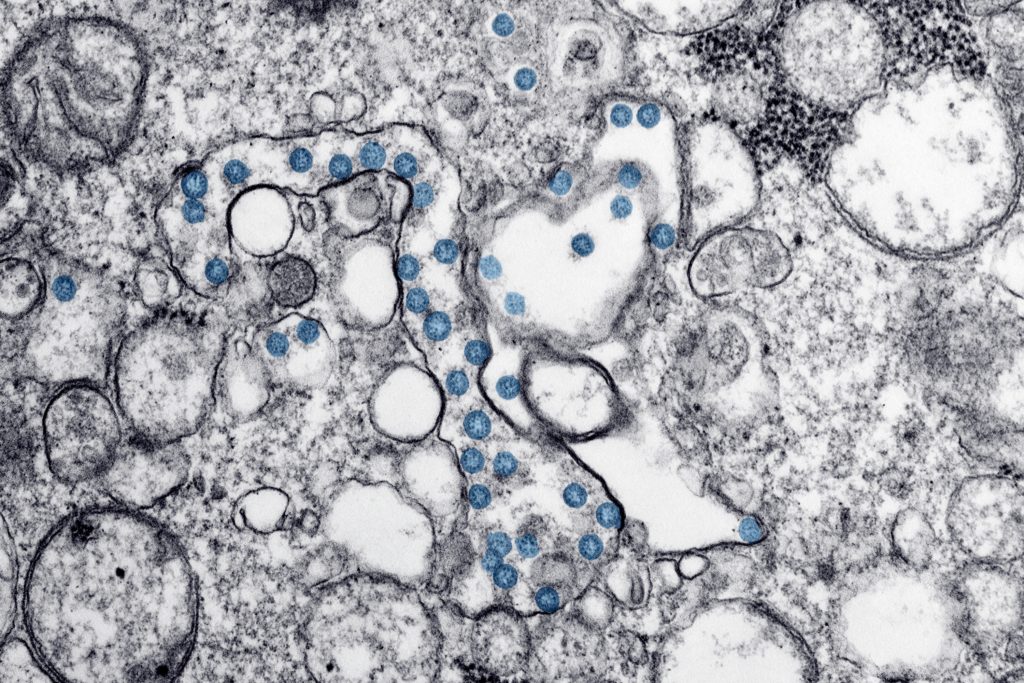

COVID-19 coronavirus viral particles are colored blue in this transmission electron microscopic image. (Hannah Bullock and Azaibi Tamin/Centers for Disease Control)