A look at kidney disease and ways to help Toby Chess

By onAnnouncements | Associations | Business Practices | Education | Technology

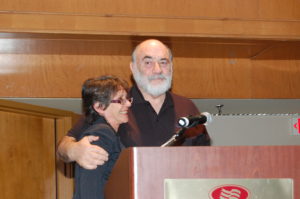

Collision industry trainer, mentor and Hall of Eagles member Toby Chess is among the many Americans suffering severe kidney disease, undergoing dialysis and in need of an organ from a living or deceased donor.

Colleagues have started a GoFundMe fundraiser to help Chess.

“Toby Chess is known throughout our industry, not only as an amazing instructor with a plethora of technical knowledge, but for his willingness to give of himself, impart his knowledge to others and to ALWAYS do the right thing,” the GoFundMe campaign states. “Always the first to step forward and help others, our industry has the opportunity to pay it forward to our dear friend Toby, who is valiantly battling kidney failure as COVID-19 cripples his teaching schedule.

“He has spent his life in service of others within our industry, and now has the opportunity to feel the reciprocal support from an industry that appreciates what he has done. Currently, Toby is undergoing dialysis three times a week, for four hours per treatment. This fund represents a way for an industry that is grateful, to recognize a wonderful man for his decades of service and volunteerism. For anyone that has ever been inspired by his words, motivated by his articles, informed by his seminars or videos, or simply touched by his generosity in sharing information.”

Contributions can be made here.

Chess’ high-profile example might leave collision repairers and other colleagues curious about kidney disease and organ donation as well.

The Centers for Disease Control estimates about 15 percent of U.S. adults have some form of chronic kidney disease, with nearly all unaware they have it. Simple blood and urine tests will tip off doctors to the presence of the condition. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease said people with high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease or a family history of kidney failure are demographics that particularly should get tested.

The illness leaves excess waste and water within the body — the damaged kidneys aren’t able to filter out the substances to the degree a healthy kidney would. Heart disease and stroke risks increase, and more specific illnesses like anemia or a weakened immune system can arise if the condition worsens.

Some forms of kidney disease are manageable. However, Chess has Stage 5 chronic kidney disease, which is considered complete kidney failure. Ongoing dialysis is necessary to live.

The dialysis process serves as a replacement for failed kidneys by artificially removing waste and water from the body, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Reaching a state of chronic or end-stage kidney failure stage leaves a patient on dialysis permanently unless he or she can get a new kidney.

According to the American Kidney Fund nonprofit, most patients have to wait 3-5 years before a kidney is available from someone who has died. Chess’s transplant facility, the University of California, Los Angeles, says the Los Angeles-area wait time is 5-10 years.

However, living Americans are permitted to donate a single kidney or a piece of a liver to whomever they choose.

“Kidney is much more common,” said Anne Paschke, spokesperson for the United Network for Organ Sharing, the organization that manages the national transplant list.

Last year saw “nearly 7,000” kidney transplants related to living donors, she said.

Prospective donors should contact the prospective recipient’s transplant center, which will evaluate whether the donor’s blood type and antibodies are an appropriate match. Though it’s possible some of the preliminary testing can be done in the donor’s home area, prospective donors should still start the process by contacting the recipient’s local transplant center, Paschke said.

For Chess, donors would visit www.uclakidneydonor.org and provide his name, Toby Chess, and date of birth, Aug. 6, 1945.

About one in five donors are healthy enough to provide a kidney, according to UCLA. Assuming that threshold is met, blood type and antibody compatibility are the two main variables tested to determine a match, according to Paschke.

A person with Type O blood can only receive a Type O person’s kidney. Someone with Type A blood needs either a Type A or Type O person’s kidney, and someone with Type B blood must have a Type B or Type O donor. However, Type AB blood means a recipient can use a kidney from any of the four blood types. Rh factor (the + or – associated with a blood type) only matters “in some very rare cases,” Paschke said.

It’s still possible for a donor to help their intended recipient even if both parties aren’t a match, Paschke said. A donor who isn’t a match for their intended recipient can be set up with a paired exchange.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say Person A wants to donate to Person B and Person C wants to donate to Person D, but neither is a match for their recipient. But if A and D are compatible and B and C are compatible, then A donates to D and C donates to B. The two donors have still given a kidney, and the two intended patients received one, so it all works out. The transplant center would set up such a pair donation.

The transplant center can sort all the willing donors and their desired recipients and see if a paired match would work. Paschke said some trades even involve more than two pairs of donors to obtain the required results.

Even if a pairing scenario doesn’t work with the known donor-recipient pairs on the books, it’s possible that a new pair or even a single, nondirected donor — a person willing to donate a kidney to anyone — will arise to set off the chain.

In the case of the latter, “they will start another link in the chain,” Paschke said.

It’s even possible sometimes with certain medical techniques to achieve a transplant using an incompatible donor, but Paschke said “they are not common” at every location.

Paschke called the need for donations “really grave.” There’s 110,000 people on the transplant list, and about 80 percent are waiting for a kidney, she said.

As of late Tuesday morning, 92,215 of the 109,215 people on the transplant list needed a kidney. Between January and July, 7,153 deceased and 3,110 living people donated at least one organ.

A living organ donation isn’t for everyone, but Paschke did encourage everyone to sign up to donate after death. “That’s something that we all should do,” she said.

Those who didn’t register to be a deceased organ donor through their DMV could sign up through a link on her organization’s website. (It’s all the same database, but there’s no harm in signing up on both if you want — you won’t be double-counted, she said.)

You might help more than one person after death. For example, though 7,153 people donated organs after death between January and July, physicians performed 19,013 transplants, according to the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

More information:

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases kidney disease information

Centers for Disease Control 2019 kidney disease facts

United Organ for Organ Sharing transplant FAQs

American Kidney Fund transplant information

UCLA kidney transplant information

UCLA living kidney donor website (Prospective donors to Chess would need to provide his name and DOB: Toby Chess, Aug. 6, 1945)

U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network waiting list and donation data

Images:

Toby Chess, right, hugs his wife, Sheila, after winning one of many Society of Collision Repair Specialists honors. (Provided by Aaron Schulenburg/SCRS)

It is possible for living people to donate a kidney. (MicroStockHub/iStock)