Collision Hub: Capture more keys by listening more, avoiding ‘weeds,’ ‘soapboxes’

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Market Trends | Repair Operations

Collision repairers having difficulty capturing customer keys might be talking about the wrong things, according to a Collision Hub broadcast Monday.

In fact, the auto body shop shouldn’t be talking very much at all, just listening, Collision Hub CEO Kristen Felder told viewers in the first live session of the company’s free “World Fair” event, which will feature multiple education sessions live through Nov. 20.

The Monday morning show focused on a shop’s initial conversation with customer, something Felder argued was essential to converting an inquiry into a repair order. The class also proposed some of its lessons could be used in interactions with adjusters.

“Being successful in this industry comes down to a lot of psychology,” she said.

Customers have experienced a loss, and this makes one “vulnerable,” Felder said. The customer also must engage in a process they don’t know anything about, she said.. Insurance adjusters also might feel vulnerable about going into a body shop, for the adjuster isn’t a subject matter expert, she said.

Trust and comfort

This vulnerability can lead to trust issues for both of these visitors, Felder said.

For the customer, the default is to trust someone they’ve known longer — which can be the insurer who has “indoctrinated” the consumer with ads, she said.

Fellow panelist Mark Olson, CEO of Vehicle Collision Experts, said customers have an “ongoing relationship” with their insurer through its television ads and trust it more than the auto body shop.

Repairers have to face what Felder called the “trifecta of communication barriers.” Shops have more to overcome than anyone else to reach the same level of trust with the customer, she said.

“We really stink” at communication in the collision repair industry, she said. A shop’s comfort zone rests with the physical vehicle, she said. The shop falls back on that and winds up leaving the customer in “non-trust land.”

The shop needs to make the customer, “not the process,” feel like the repairer’s No. 1 priority, Felder said.

You need the customer to feel empowered, not overwhelmed, she said. If a consumer is overwhelmed, they’ll default to what will make them feel more comfortable. “That’s not us,” she said. Often, it’s going to be the insurer and its solution.

Rules for improvement

The show offered several suggestions for improving customer communications to capture more keys.

Felder called speaking less than than the customer the most important rule of communication presented in the session.

80 percent of the conversation should be the consumer talking, Felder said. Get them talking, and “if you listen good enough,” they’ll tell you what they want, she said.

“Talking is a control,” she said. Listening is hard.

Repairers mistakenly believe customers want them to swoop in: “‘I’ll take care of this.'”

However, “we tend to overwhelm the customer,” even with kindness and “good intent.”

Instead, get the customer talking with open-ended questions — the who-what-where-when-why-how journalists use, she said.

Felder said research at Stanford have found that responding to questions builds trust in the questioner. This means each question a shop asks builds a little more consumer faith in the facility, according to Felder.

Your job is to deliver on the customer’s expectations — not yours, Felder said. Repairers focus on the idea that customers deserve a good repair — but the act of delivering it isn’t going to exceed the customer’s expectations, as she described it.

“That’s all assumed,” Olson said. The customer thinks a proper repair will be the default in the industry.

Definitely, “don’t pontificate,” Felder said. She noted that she could talk for hours about a repair procedure, but the customer’s “checking out” mentally.

A shop might think explaining how the customer runs the risk of death without a steering wheel reset builds trust with the customer, but it actually does the opposite, she said. Ask the customer questions instead and “watch your soapboxes,” she said.

Don’t get on a soapbox complaining about the insurer, the OEM procedures, or the shop down the road, she said.

“Don’t be predictable,” she said. The insurer tells a customer that the repairer will be difficult or cost too much — and then the repairer validates it in the customer’s eyes by acting “difficult and angry,” she said.

In a similar vein, “stay out of the weeds,” Felder said. Collision repairers “like to overwhelm customers” with information like documentation and position statements, she said. But the customer might not care about it, she said.

She said she’ll instead give the customer a link to a Google Drive repository of that documentation and estimates with reference notes to that documentation. The customer can study the information at their leisure and call with any questions, she said.

Felder said she would explain an estimate in broad strokes — “parts,” “labor,” etc. — and then turn the conversation over to the customer to explore whatever area the customer wished first.

She said she would also identify possible points of contention with the insurer and ask if the customer wanted to discuss them further. If the customer sought more detail, Felder would explain the issue simply — not present a gigantic stack of documentation.

She used the analogy of going in for heart surgery: She would want to know what the doctor planned to do, but “I don’t want to become a heart surgeon when it’s over.”

The same applied when dealing with an adjuster, Felder said. An overwhelmed adjuster will retreat to a comfortable place, which is “‘no,'” she said.

So be brief. Felder said a repairer might feel like they’re full of “really cool” information to share, but it can overwhelm a customer desperately trying to understand the process. The more a customer feels overwhelmed, the “comfort spot is no,” she said.

She cited an old simile: “‘Conversations are like a miniskirt. They should be short enough to keep your attention, but long enough to cover the topic.'”

Felder cited more Stanford research related to a government health program change. Seniors had to select from different options, and the government was trying to figure out how to best to explain the choices. Stanford found that the more information consumers received, the more likely they were to select a choice not in their best interest. Receiving less information led to consumers making better decisions.

“That’s just flat-out science,” she said. It goes

Olson said the shop’s goal isn’t to impress the customer with its knowledge. The goal is to capture keys, he said.

Don’t repeat yourself when you do speak. “It’s just annoying,” she said. Still other Stanford research has found repetition will start to isolate and embarrass the other party, she said.

If a consumer asks about something you have already covered, then restate your answer so the point gets across, Felder said. If your verbiage didn’t work the first time, then don’t repeat that wording verbatim, she said.

It’s OK not to have all the answers, according to Felder.

Humility is a major strength, Collision Hub director of industry relations Jason Bartanen said on the show. A shop that seems to have the answer to everything might leave the customer wary of being lied to, he argued. Saying you don’t know and will have to research an answer builds trust, he said. “It’s a huge communication piece,” he said.

“They come in vulnerable,” Felder said. A shop acknowledging they don’t know an answer either delivers a sense of relief, she said.

Repairers see not knowing as a weakness, but “it really is a strength” in dealing with the customer, Bartanen said. As he put it, no one ever complains that their doctor had to conduct tests and do research to determine an ailment rather than have an answer immediately.

Don’t equate your experience, she said. Telling a customer you’ve fixed 100 similar cars is the wrong response, she said. For in the customer’s eyes, “‘You haven’t fixed mine.'”

“Make sure that you allow the customer to be special,” she said. “It is not about you.”

If you can make these interactions always about the customer rather than the repair, you will succeed, she said. “They will fight for you,” she said.

She also observed that equating an experience is the incorrect move to use on an adjuster as well. Tell an adjuster that a colleague at their insurer or a representative of another carrier pays for something, and they’ll just get made, she said.

Go with the flow. Don’t fight the conversation or shift to a different topic, she said, joking about a shop who greets the news that a customer’s cat died with “‘Let’s talk about your bumper.'” Let the customer talk.

Felder said the same holds true when she visits shops for audits. She’d like to get to certain key items and leave, but it’s critical to sit back and let technicians organically reach the point she’s trying to make. Trying to force them there will lead them to reject it.

Finally, don’t multitask, Felder said. “Everything goes away” when you’re dealing with a customer or adjuster, she said. Leave the cellphone on your desk, and don’t bring out a form to fill in.

“I really want you to have a conversation with the customer,” she said.

Implementing and tracking results

Shops shouldn’t try and pull off all these new techniques at once, Felder said. Practice on friends, co-workers or relatives, she said. Try it with a vendor, she said, joking that since they’ll take up your time, “use them as guinea pigs.”

Felder also recommended asking front office staff how comfortable they feel with communication and to educate them in the lessons of the class.

If you’re trying to pick one technique to introduce first, “just learn to listen,” Felder said. Get comfortable with that, and six months later, see if staff feels more comfortable communicating and your closing rate has increased.

“You should know your closing ratio,” she said. How many interactions lead to a closed repair order, and how many lead to a no-show or the car removed from your facility?

Fellow panelist Larry Montanez, co-owner of P&L Consultants, said repairers will measure closing ratio by comparing the number of estimates written to the number of customers who return for the repair. That’s incorrect, he said.

It’s customer interactions — minus the customers whose work you intentionally refused — compared to keys captured, he said.

Shops are writing estimates instead of talking to the customer, he said, and Felder earlier observed she opposed drive-in estimates for the same reason.

Montanez described a scenario he has noticed on shop visits. The repairer meets a customer, realizes the customer isn’t immediately about to hand over the vehicle and writes a “real crappy, 12-line estimate.” Then the shop comes back with a gigantic supplement, and the customer asks what’s going on.

Shops have the mentality of “‘I gotta write you a piece of paper,'” he said. But the customer’s need is actually for their car to be fixed, not an estimate, according to Montanez.

More information:

“Collision Hub’s World Fair & Expo – Crucial Conversations: Winning The Customer’s Trust”

Collision Hub YouTube channel, Nov. 9, 2020

Images:

Are you building trust with a customer at your body shop or driving them away without capturing the keys? (Hispanolistic/iStock)

Collision Hub CEO Kristen Felder speaks during a 2020 “World Fair” session on conversations with customers. (Screenshot from Collision Hub YouTube video)

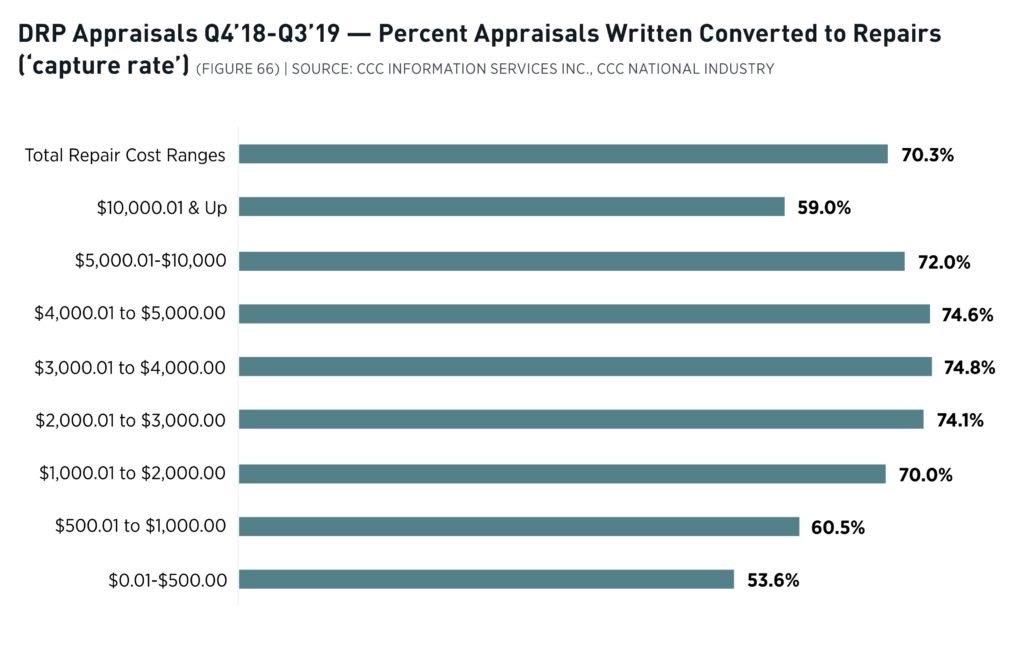

The 2020 CCC “Crash Course” reported that for the year ending in the third quarter of 2019, DRP shops captured the keys on 70.3 percent of appraisals. (This appears to be a reference to the subset of initial appraisals generated by the DRP shop instead of the insurer or some other party, but it wasn’t entirely clear from the report.) (Provided by CCC)

From left, Collision Hub industry relations director Jason Bartanen, Vehicle Collision Experts CEO Mark Olson, P&L Consultants co-owner Larry Montanez and Collision Hub CEO Kristen Felder hold a “World Fair” session Nov. 9, 2020, on body shop conversations with customers. (Screenshot from Collision Hub YouTube video)