Mitchell exec: Estimating systems need to evolve to meet challenge of EVs

By onAnnouncements

Electric vehicles (EVs) are far more complex to repair than their internal combustion engine counterparts, and current estimating systems need to evolve to meet their needs, the director of claims performance for Mitchell’s Auto Physical Damage unit told an audience Thursday.

“We need to be taking a new approach to preparing an estimate on an electric vehicle,” Ryan Mandell said during a CIECA webinar. “We need to understand that these vehicles are very different when they go into the repair facility. Things that need to be done to them are completely different. They are more complex than the standard internal combustion engine vehicle out there. And thus, the estimate needs to be prepared in a more advanced fashion as well.”

Though EVs now make up only about 1% of repairable claims and estimates, “that’s something we expect to continue to grow,” Mandell said. Some aggressive estimates say that 50% of the nation’s car parc will be electric by the mid-2030s, though Mandell predicted that it would take 20 years to reach that milestone.

In the U.S., between 2020 and 2021, the sale of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and EVs as a percentage of overall vehicle sales grew by 96%, Mandell said. “This is really important to remember, as we think about these vehicles coming into our repair facilities, and what that means for technicians, what that means for the repair process, the estimatics process, and how we underwrite these vehicles.”

“It’s really important to understand that an EV is not just an electrified variant of an internal combustion engine vehicle – it really is something totally different,” Mandell said. “Even though on the surface the vehicles may look similar, the architecture is totally different and unique. And these vehicles need to be treated as such.”

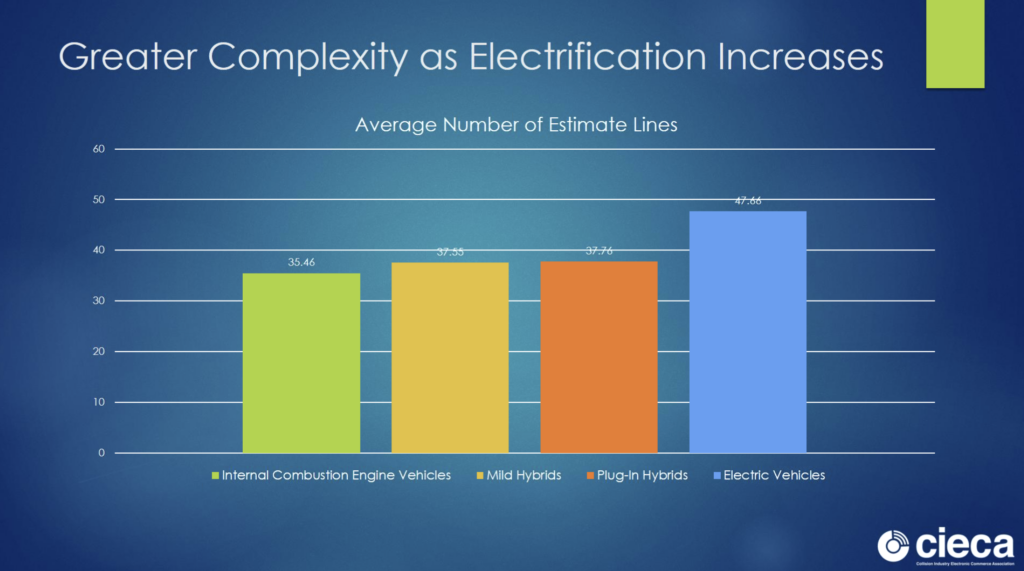

According to Mitchell’s data, repair estimates for EVs have an average of 47.66 lines. That’s 10 more lines than for ICE vehicles, and a leading indicator of differences in repair complexity, Mandell said.

Scanning data backs this up, he said. While EVs are scanned at roughly the same rate as all other vehicles, they turn up, on average, an additional five fault codes. That’s based on data from 3 million scans of 2015 and newer vehicles handled by Mitchell.

One reason for this, Mandell said, is the advanced technology incorporated into EV design. According to federal Commerce Department data, EVs on average contain about 2,000 semiconductors, more than twice the number typically used in ICE vehicles.

In an EV, electronics are carrying out some of the tasks done with mechanical components in ICE vehicles, he said. “Certainly that technology has advanced in traditional vehicles as well, but it’s on the cutting edge with electric vehicles. And so when you have a front end accident, the likelihood of secondary and tertiary systems being impacted across that electric vehicle is far greater than on a vehicle that has just a traditional internal combustion engine.”

For instance, he said, because the systems are so interconnected, “a front end accident has the potential to actually impact systems on the right rear corner of that vehicle.”

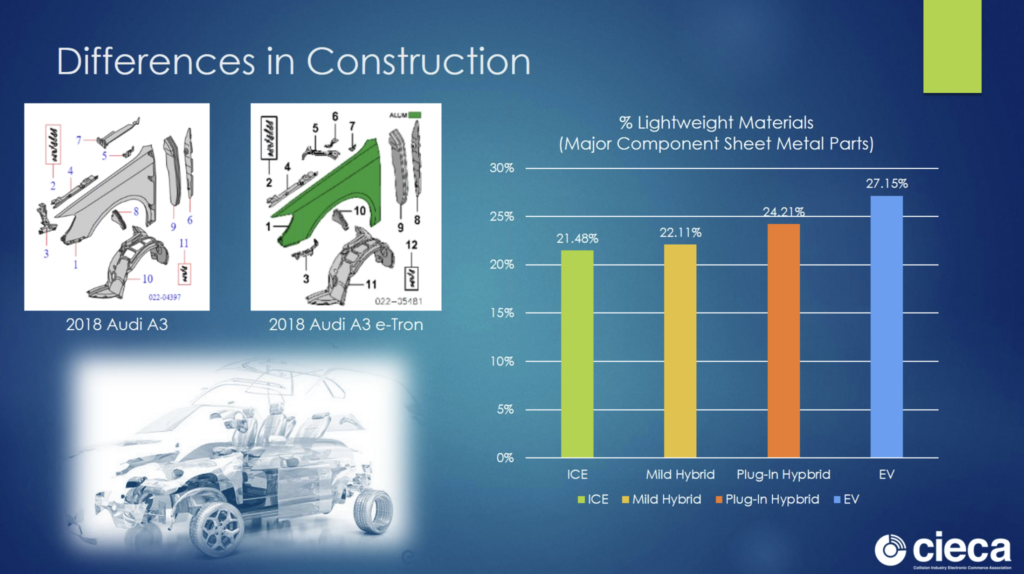

Mitchell conducted a study of sheet metal components such as hoods, fenders, doors, quarter panels, and deck lids and found that the further a vehicle moves toward full electrification, the more complex these parts become, too.

A little more than 27% of an EV’s components are made of lightweight material, such as high strength steel (HSS) or aluminum, compared with 21.48% of an ICE vehicle’s components. This is because OEMs need to compensate for the great weight of EV battery packs, Mandell said.

Lightweighting “really changes the way that these vehicles respond in an accident, and the repairability of the vehicles as well,” he said. Aluminum, for instance, becomes brittle when it crumples in an accident so those components are much more likely to need replacement rather than repair.

Mandell offered the example of the 2018 Audi A3 and the electric Audi A3 e-Tron from the same year. Although the diagrams of the construction of the left front fender show similar components, the e-Tron’s fender is made of aluminum, while the A3’s is steel.

“Aluminum versus steel is going to be a different decision-making process, in terms of whether you’re going to repair or replace it,” he said. This could extend to a need for different types of tooling and equipment to make the repair.

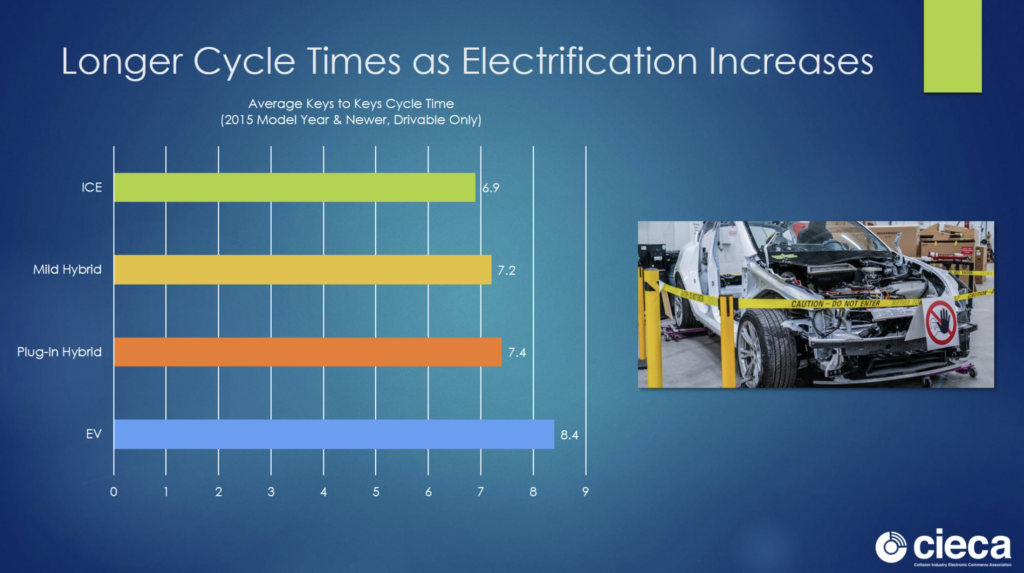

These factors all contribute to “significantly higher cycle times for EVs compared to the other propulsion types,” Mandell said. According to Mitchell’s data, the average cycle time for an EV is 8.4 days versus 6.9 days for an ICE vehicle.

Part of the additional time, he said, is accounted for in the safety measures that must be undertaken to protect technicians from the dangers presented by the high-voltage battery pack.

“It’s exciting to see all of the education and all of the tools that are available now to help people understand the right way to go about repairing these vehicles and understand the precautions that need to take place before we even get into a basic teardown,” Mandell said.

There can be other factors, too, he said. For instance, Audi says that the battery pack of the A3 e-Tron cannot be submitted to the temperatures inside a paint booth. “That battery has to be removed, and that’s an additional two labor hours that take place,” he said.

Body shops and insurers can help their EV-owning customers understand how their vehicles are different, and how that affects the repair process, Mandell said.

“I think that really sets up the overall outcome to be a positive one. I think it sets …the expectations appropriately for the owner, and …does the same for those that are actually doing the repairs on the vehicle. Because if that’s something that’s being kept top of mind throughout the entire process, I think you end up with really high quality results, both from a quality control standard and from a customer experience standard.”

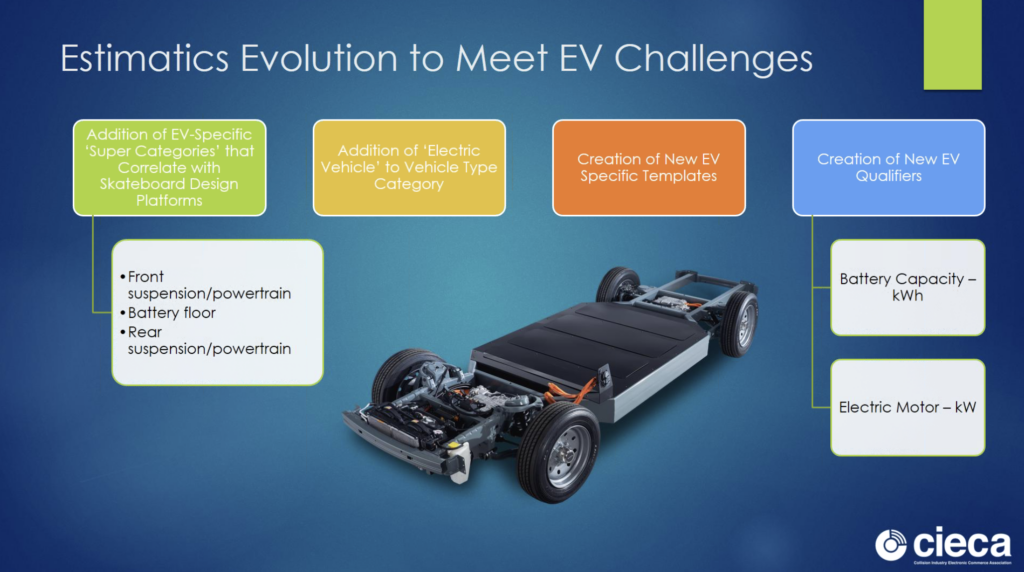

The differences between EVs and ICE vehicles mean that the same template can’t easily be used for writing estimates on both, Mandell said. He said this is an issue that Mitchell is addressing, “to make sure that the estimatic system is really built in a way that facilitates success, that facilitates that safe and proper repair, to make sure that the outcome is the highest quality in terms of the actual repair itself and the highest quality in terms of that customer outcome, and is efficient as well.”

Because certain aspects of an EV “simply don’t exist” with an ICE vehicle, a number of EV-specific supercategories need to be added to the estimating system, he said. Among these are the front and rear suspensions, which might incorporate multiple electric motors, and the battery floor, which is unlike the mild steel floor usually encountered in a non-EV.

“This is a totally different type of vehicle, and we need to treat it as such,” he said. “The way that you’re going into this vehicle, and the way you’re thinking about it, from the very beginning, really kind of helps guide you through the process, not only in writing the estimate but in preparing a repair plan.”

“I think we’re going to be getting to the point where we’re actually being proactive about some of the technology that’s going to be coming out and being able to get in front of some of this before it actually hits the market,” he said.

More information

Charged for Success: Understanding EV Trends and Their Impact

Images

Featured image by deepblue4you/iStock

Graphics supplied by Mitchell/CIECA