IIHS to use virtual testing to rank seat & head restraints

By onAnnouncements | Technology

The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) says it’s developing a new rear impact testing system to measure how seat and head restraints protect vehicle occupants.

Marcy Edwards, an IIHS senior research engineer, said in an article published on the organization’s website Tuesday that virtual testing will be used to determine how modern restraint systems perform in a variety of scenarios.

She detailed how the multi-step process will involve using testing with computer models as well as conventional tools used in IIHS’s original head restraint test.

“We’ll also need the help of scientists developing detailed computer models of the human body and the cooperation of vehicle manufacturers,” Edwards said.

When sharing how the testing could work, she said one challenge is that IIHS can’t purchase computer models of seats to conduct simulations as they’re the intellectual property of OEMs, meaning the testing process will require automaker cooperation.

“At the same time, we’ll need to structure this cooperation so that it doesn’t compromise the independence of the testing program or the trust consumers place in the results,” Edwards said.

“We have a long and successful history of accepting test data from physical crash tests conducted by automakers for many of our ratings. In many cases, we allow established manufacturers to conduct tests according to our protocols and then supply us with video and other data so that we can verify the results and assign ratings.”

She said those videos are randomly audited to ensure the accuracy of the crash test outcomes and that IIHS intends to build onto such a system as it expands into virtual testing.

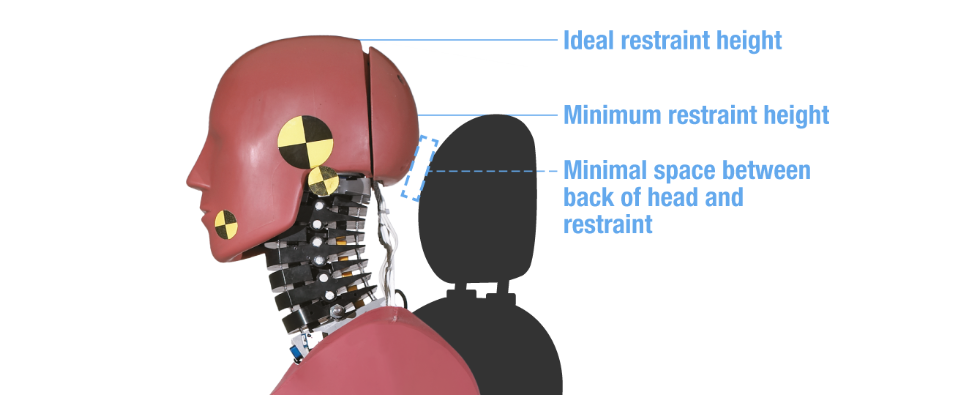

Although IIHS began rating head restraints in 1995, Edwards said the initial measurements were simple and involved a dummy representing a man of average height.

At the time, 82% of head restraints tested received poor geometric ratings, inspiring OEMs to improve their vehicle design, she said. But although good geometry is necessary, it isn’t enough, Edwards added.

“Seats can differ in other ways too, such as structure placement, seatback stiffness, and energy-absorbing properties, all of which can affect outcomes for occupants,” she said.

Organizations conducting crash tests have been working to ensure the results represent the true impact that would be sustained by both men and women. Last year, a new generation of crash test dummies by safety testing equipment company Humanetics was released that focus on improved biofidelity, or a more human-like design, as well as a more accurate representation of females.

To better conduct rear impact evaluations, IIHS added a dynamic test for vehicles in 2004 with “good” or “acceptable” ratings to determine how well the seat and head restraints managed crash energy and occupant motion, Edwards said.

That test involved a simulated rear impact collision with the seat mounted to a sled. A special dummy with a realistic spine, called BioRID, was buckled into the seat and tested in a rear-end collision scenario equivalent to being rear-ended by a vehicle traveling 20 mph.

By using geometrics and dynamic tests together, Edwards said IIHS was able to identify the most effective head restraints.

She said it’s now time to take the evaluation further.

“Since we began dynamic testing, manufacturers have gotten very good at designing seats for the 10 mph velocity change and today’s vehicles all perform well in that test,” Edwards said. “However, there are still differences in real-world performance. Insurance claims data collected by my colleagues at the Highway Loss Data Institute suggest that injury rates in rear-ended vehicles with good head restraint ratings vary widely.”

IIHS plans to add a second dynamic test with a larger velocity change of 15 mph, Edwards said and intends to launch a new rating program that encompasses both tests within the next two years.

“Beyond test speed, other variables are harder to tweak. As is the case with all crash test dummies, BioRID has limited capabilities — for example, it’s only valid for fore-aft motion and lower-severity crashes — and doesn’t represent the diversity of the driving population,” Edwards said. “While it is an impressive tool with something that closely resembles a human spine, it represents the specific spine of a 50th percentile male.”

Edwards said that no matter how sophisticated dummies become, they still can’t determine how soft tissue and nerves can be damaged in a crash, or how a crash might affect people of different body types and genders.

“On the other hand, computer models of the human body, which are currently under development, could be more easily varied to represent a range of body types and injury risk factors,” Edwards said. “Virtual testing with these models could someday soon provide us with the ability to see how seats and head restraints function for many different people sitting in different positions.”

As it expands its testing, IIHS said it will give OEMs the option of submitting virtual test data for its new 15 mph test and existing 10 mph test. This will help it become accustomed to working with virtual test data, Edwards said.

From there, she said IIHS will expand the number of required test scenarios to potentially include variables like speed, seat position, and the position of the passenger.

“Our plan is to eventually expand the required virtual tests to include scenarios that can’t be tested in the real world because of the limitations of the dummies and other tools we have,” Edwards said. “This is where we’ll be able to evaluate performance with occupants of different body types and also in different positions that can’t be achieved by a physical dummy.”

To ensure accuracy, Edwards said IIHS will conduct physical tests for some of the same virtual tests to ensure the results are accurate.

“Replicating some results and then ensuring the same seat and dummy or human body models are used throughout the virtual evaluation will help us validate all the results, including the ones for scenarios we can’t physically test,” she said. “The road map we’ve laid out will allow us to move into this new territory carefully and deliberately. And as we learn from this first experience, we’ll be able to apply this knowledge to other crash types, potentially spurring a wide array of vehicle safety improvements.”

Images

Featured illustration courtesy of angelhell/iStock

Secondary images courtesy of IIHS: In the third image, a sled test simulation is shown using the BioRID-II FE model for LS-DYNA software compared with the IIHS sled and BioRID dummy.