GMG experiment questions auto repair gear’s isocyanate protection

By onEducation | Repair Operations

GMG Envirosafe Chief Operations Officer Brandon Thomas has caught the attention of the auto body repair and personal protective equipment industries with an informal test that found isocyanates penetrating some common paint suits.

Thomas on Monday described the test as “very basic,” an effort to get a “quick glance” into the capabilities of six commercially available suits to protect against the hazardous chemicals, which are the building blocks for polyurethane products such as paint.

Test findings were presented last week at the Collision Industry Conference in Palm Springs, Calif.

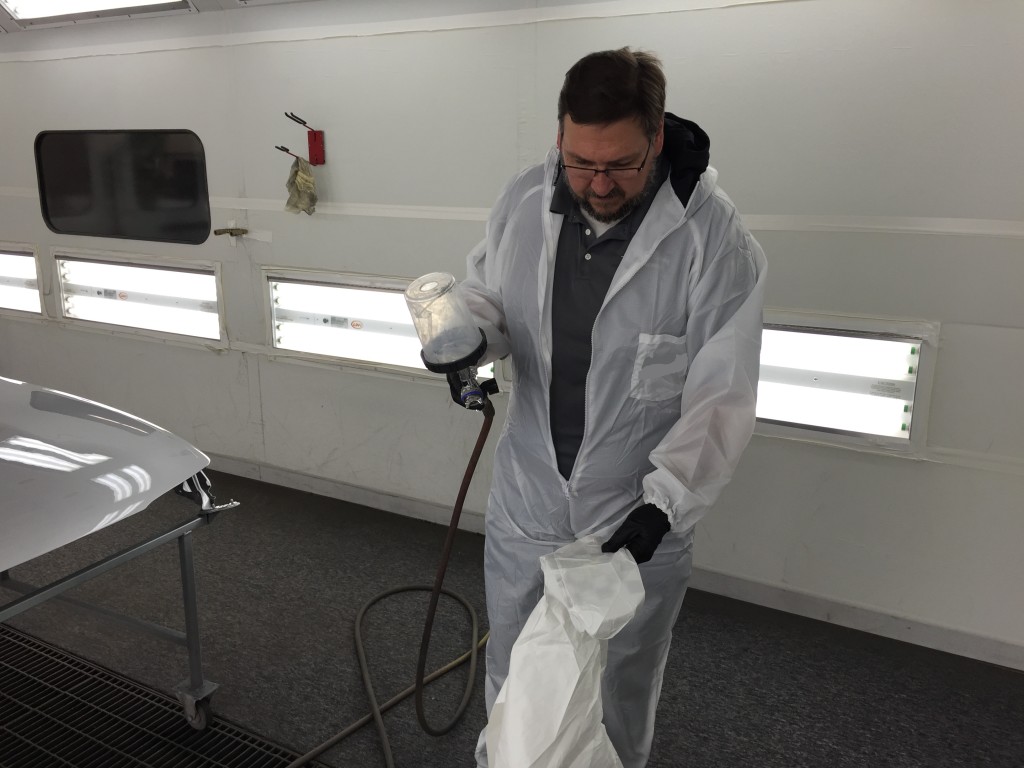

A suit is tested for isocyanate penetrability by GMG Envirosafe. GMG has intentionally obscured the logo of the manufacturer in this image. (Provided by Brandon Thomas/GMG Envirosafe)

Isocyanates and inspections

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration announced in summer 2013 that it would for three years take an increased interest in isocyanates, which can cause irritation and breathing issues such as “work-related asthma.”

OSHA’s National Emphasis Program includes a random series of business inspections by area offices. Every office has to do at least three a year, and wrap up a cycle of five inspections before randomly picking new businesses. That’ll go on until the NEP or list of businesses runs out.

Inspections will include air and surface sampling, including in gloves and respirators and possibly on skin if it looks like contamination happened.

Skin contact is a big concern. In addition to irritating the epidermis itself, isocyanates on the skin are just as likely to cause breathing issues as if you’d inhaled them, according to OSHA.

And even more troubling is the factor that while OSHA has determined the amount of isocyanates in the air that would be hazardous to your employees (and get you cited), there’s not enough evidence to show how much you can risk getting on your skin. Therefore, you could potentially get in trouble for any level of surface or skin contamination found, according to OSHA.

“Basically, the rule is none,” Thomas said.

Suit integrity

Thus, ensuring your suit actually works as desired is vital to protecting your employees and your body shop. The problem, Thomas said, was obtaining proof that a suit was indeed rated to block isocyanates should OSHA request it.

Manufacturers told him no such defined tests existed, Thomas said, which led him to create his own.

It worked like this: The testor sprayed clear coat for about five seconds at a suit covering a sensor mounted on a card. The card was compared to a control test and the other suits.

“I stressed this at CIC and I will stress it again, this was not meant to recreate a working environment, but just to baseline the suits against one another and test the sensors themselves,” Thomas wrote in an email Tuesday.

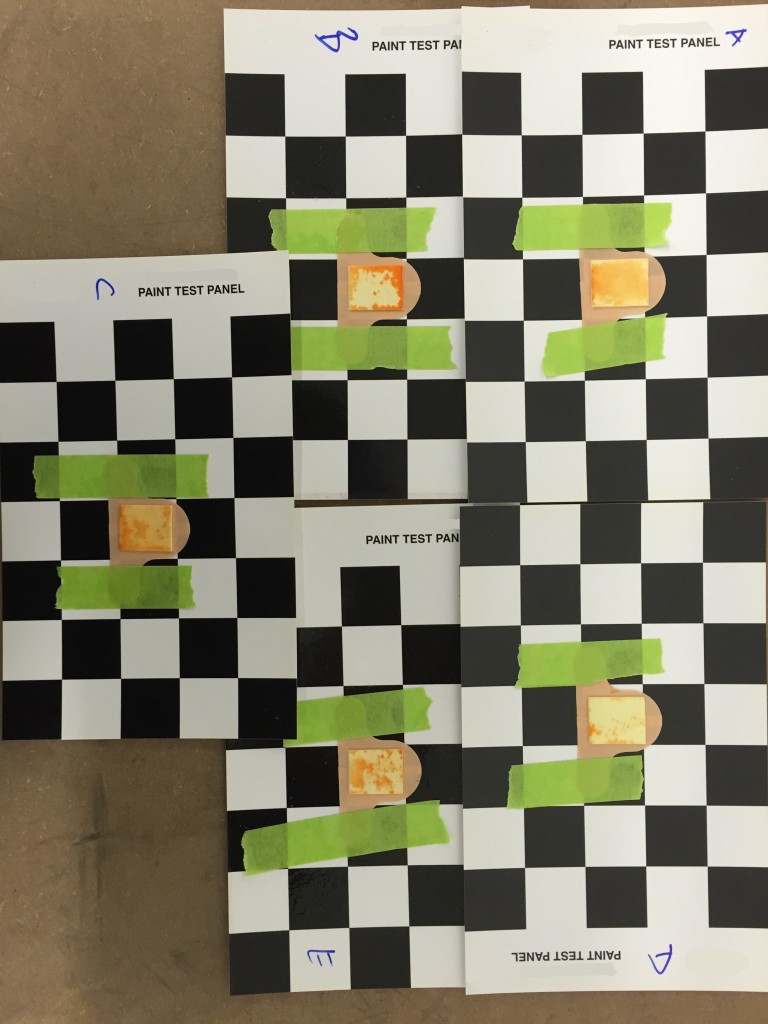

Below are the results of GMG Envirosafe tests on five protective suits. These five proved permeable to isocyanates. GMG Envirosafe has intentionally altered the image to obscure manufacturers’ names. (Provided by Brandon Thomas/GMG Envirosafe)

He found that five out of the six suits tested failed to protect completely against spray or spill isocyanates. Within those five, the amount of infiltrating isocyanates varied wildly.

“It was pretty eye-opening,” Thomas said.

Thomas wouldn’t say which suit made the cut and which five failed. The six suits were the DuPont M-5905, DeVilbiss 803599, SATA 530062w, SAS 6896, Shoot Suit 2005B, and XL 9062.

“The point of me doing it was not to point the finger at anybody,” he said. Rather, it was to point out the seeming lack of reliable data on which suits are certified isocyanate-safe for a collision repair business. (In the manufacturers’ defense, none of the suits tested were billed as isocyanate-certified before the test.)

After all, while OSHA will recognize those who made a good-faith effort, you never really know how an individual inspector will react.

“I compare it to being pulled over by a cop,” Thomas said.

Jim Sowle, body shop director at Sewell Lexus, had a similar experience. In an attempt to head off potential OSHA issues were he to be inspected as part of the isocyanate sweep, he sought to locate a suit certified to protect its user.

“It was very hard to find,” he said, noting he had to look overseas to discover one.

Some more formal studies have been done. For example, this 2013 examination by the American Chemical Council’s Center for the Polyurethanes Industry, which tested a variety of suits and gloves for how quickly polymeric methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (PMDI) passed through them (some gloves and suits, however, resisted for hours). A 2007 work in the Annals of Occupational Hygiene specifically looked at isocyanates and auto body repairers/refinishers, finding like Thomas that isocyanates were making it through some protective equipment.

Thomas said his demonstration seemed to be eliciting more clarification from manufacturers on whether or not their suits can protect the technician or just the paint job.

“I’m glad that the manufacturers are engaging with us,” said Thomas, who is planning to give an update soon based on the industry responses to his efforts.

Featured image: An Aston Martin sits in a light tunnel in the paint shop at an assembly plant on Jan. 23, 2008, in Gaydon, England. (Christopher Furlong/Getty Images/Thinkstock file)