How auto body shops can keep workers — and vehicles — safe from aluminum dust

By onEducation | Repair Operations | Technology

Aluminum dust gained more attention recently with Automotive News’ reposting ofJune 2014 coverage of the substance’s flammability that also took a look at the debate on preventing dust corrosion.

Ford, whose guidelines for body shop safety while working on the aluminum F-150 also drew attention to the issue, recommends a Wet Mix vacuum or central system to extract aluminum dust to avoid explosions.

That didn’t seem to be too controversial (aside from the cost of buying one), based on the Automotive News coverage.

Much more controversial, according to the magazine, was Ford’s recommendation of curtains to protect against aluminum-steel dust corrosion, unlike the walls required by some other manufacturers, as Automotive News reported earlier in the year.

Ford doesn’t say not to build a clean room; it just doesn’t require it for your shop to make its list of certified F-150 repairers. Any collision repairer can still work on the F-150, but the list will probably be an attractive starting point for insurers and drivers seeking to get work done on the truck.

“One of the things about our program that surprised the industry is that we didn’t require a separate clean room,” Ford collision marketing manager Paul Massie told the magazine.

Some body shop owners weren’t convinced, according to Automotive News.

“We’re going to build the walls up,” Hoffman Ford vice president Todd Hoffman told the magazine about his Pennslyvania dealership’s shop. “We may actually expand to a whole different location off site for a body shop. From what we’re understanding from the big players in the paint business and body repair, it is a pretty significant safety risk to mix steel and aluminum.”

Let’s talk about the two concerns (and a more general one) so you know why you’re spending the money on either barrier, Wet Mix gear, and the dedicated aluminum tools Ford requires to make its list. This will enable you to better explain to a customer or insurer why it was a reasonable investment to recoup with higher labor rates for aluminum.

We’ll talk about your workers’ safety first before we get into vehicle safety.

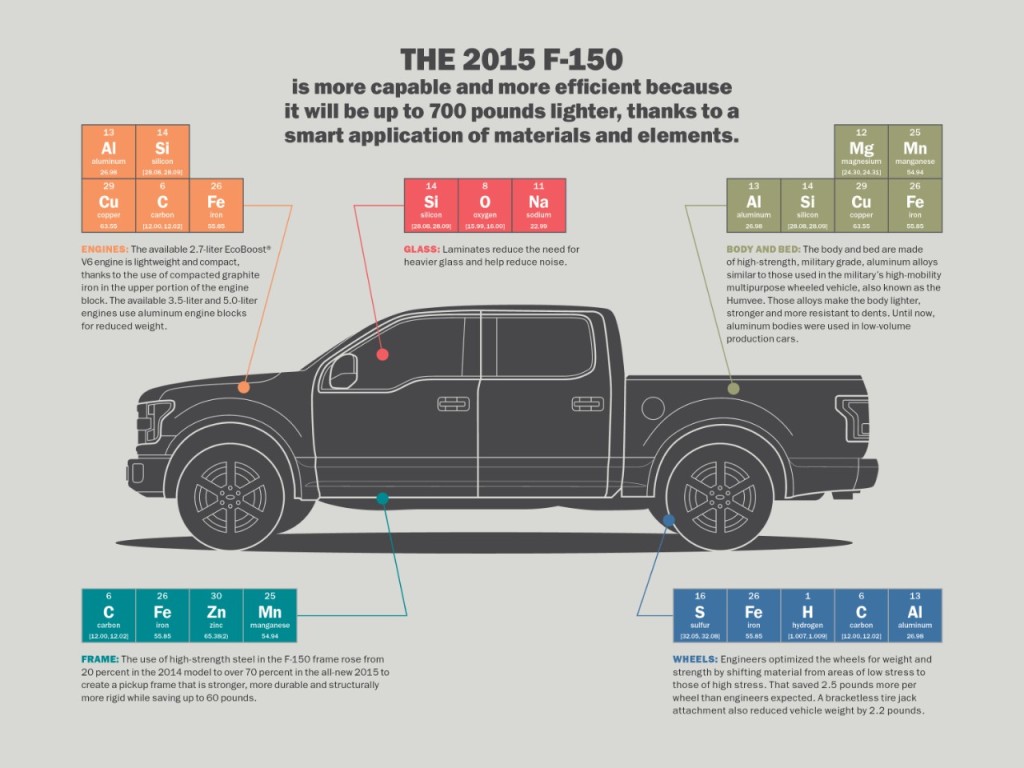

The 2015 Ford F-150 is related to the periodic table in this Ford publicity item. (Provided by Ford)

Explosion risk

Though many types of dust are explosive when concentrated, Aluminum dust poses a higher combustion risk than other metal particles. A 1964 U.S. Bureau of Mines study found that as little as 0.045 ounces per cubic foot of atomized aluminum could explode, and 0.02 ounces of powdered aluminum-magnesium alloy — which is used in the Ford F-150 — can be dangerous.

(For more on aluminum-magnesium usage in the F-150, see this Car and Driver article; check out this ESAB article for more on the alloy in general.)

This is why the Wet Mix gear is necessary to remove aluminum dust from the area safely — even at what Ford estimates to be a cost of $10,125-$17,999.

“If it happens, it’s ugly,” I-CAR industry technical support manager Steve Marks said of an aluminum explosion.

Marks, who has done training for aluminum adopters Land Rover and Jaguar, also noted that steel and aluminum can mix to create thermite for a “really nasty” explosion.

You want to make sure equipment is grounded to avoid static sparks, he said, and you’ll want to use brushless methods of removing the aluminum to avoid sparks.

Aluminum dust is also very fine and “does float a lot longer,” according to Marks. That raises issues both with flammability and with potential health risks from breathing it. (More on that shortly.)

And technicians trying to remove aluminum dust should not use compressed air, he said.

In an email Friday, Ford truck spokesman Mike Levine stressed that the combustion risk applies only to aluminum dust — not sheet metal.

“Aluminum sheet will act similar to aluminum castings and forgings, which have been used in engine blocks, chassis components and wheels for decades,” he wrote. “Aluminum is also used in cooking equipment.”

Kaiser Aluminum engineering and technology vice president Doug Richman also acknowledged the explosion hazard of aluminum dust in an interview with Repairer Driven News.

However, he argued it applied in situations with heavy, heavy dust generation, such as the fatal 2014 blast at a rim-polishing factory in China described in this New York Times article. The International Business Times reported that the rims were aluminum-alloy. Both articles raised the question of safety precautions not being taken.

For collision repairers, aluminum poses less of a risk than in that sort of setting, said Richman, a member of the Aluminum Association’s transportation group. He noted that in a century of aluminum in vehicles, there hadn’t been a sustained aluminum explosion in a body shop.

On the other hand, aluminum vehicles haven’t been as mainstream as the F-150, either.

Richman said his industry was working on a study to figure out what particle size exactly would pose a combustion threat in the air so there was a greater science informing shops what they need to do to be safe. He said in January that an estimated completion date was unavailable at the time.

Ford’s 2015 F-150 weighs 732 pounds less than the 2014 F-150, in large part because of the 2015’s aluminum content. (Provided by Ford)

Respiratory health

As Marks noted above, aluminum dust also poses a more mundane health concern in terms of inhalation and general exposure. OSHA has determined that aluminum dust doesn’t require more protection than you need for other particles in such a setting; it gives aluminum the general industry particle limits of 15 milligrams per cubic meter of air for skin contact and 5 mg/cubic meter for maximum amount you can inhale safely.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health felt there was more of an exposure concern, lowering the skin contact limit to 10 mg. It keeps the respiratory limit the same as OSHA’s but does warn against lung alterations that could create pulmonary fibrosis.

California has also enacted that 10 mg rule for overall exposure and puts the breathable maximum at 5 mg.

Corrosion

We’re going to explain the corrosion that could happen at your collision repair company as painlessly as we can, but we’ll cut to the chase for the impatient:

Mild or stainless steel corrodes aluminum, but aluminum corrodes galvanized steel.

That’s the moral. Remember that as you work on vehicles. Frame it and put it on the wall for your fellow staffers.

And now, the chemistry lesson, thanks to the assistance of corrosion engineer Dan Barlow at the American Galvanizers Assocation and NASA’s Corrosion Technology Lab at Kennedy Space Center. We’re going to simplify things a little for readability, so they and other scientists are probably wincing somewhere.

All metals except copper and the precious metals are not in their desired metallic state when you find them “in the wild.” You’ve got to submit the ores to some sort of process to keep them in the metal form you want. Once you get them there, the metals want to revert back because the former state requires less energy.

This entropy speeds up when the metal and something that can “take” the energy are in an environment that encourages that transfer. In this case, we’re looking at the galvanic reaction from two metals touching in the presence of water containing an electrolyte. Basically, that’s any water that isn’t distilled — including the moisture in the air. Another common form of corrosion involves metal giving away electrons to oxygen when the two are touching water; that’s how iron rusts out in the air.

In the galvanic reaction, the least reactive metal (known as the cathode) gains electrons from the more reactive anode and corrodes it. Scientists have developed a baseline galvanic scale of metals ranking them from the noblest — cathodes least likely to corrode — to the most highly reactive, or anodic, substances when in contact with seawater. (The salt serves as the electrolyte for the reaction.)

Anything higher on the scale corrodes everything below it. The whole list is here, but for our purposes, we’ll cut it to a few.

NOBLE –>

Stainless steel

Mild steel

Iron

Aluminum

Galvanized steel

Zinc

–> ANODIC

So as we said: Mild or stainless steel dust will corrode aluminum, but aluminum will corrode the galvanized steel that makes up a large percentage of your average vehicle.

Jody Hall, vice president of the Steel Market Development Institute, said galvanized steel makes up about 80 percent of the steel on vehicles. The rest is generally bare steel that is completely enclosed, such as above the beltline.

More accurately, aluminum corrodes the zinc coating which covers the steel. Galvanized steel resists corrosion by having its zinc shell “take one for the team” and oxidize into a protective coating instead of letting the underlying steel — which is really just iron at heart — corrode and lose integrity.

In your shop, that can mean the aluminum dust on a galvanized steel part will cause rust spots to bleed through the paint job you painstakingly applied, according to Automotive News.

Generally, corrosion between aluminum and either steel “will be noticeable over months, for sure,” Barlow said, possibly as soon as within weeks.

However, the size of the cathode compared to the anode also affects the reaction speed, he said. This means that an aluminum bolt in a giant sheet of ungalvanized steel will corrode more quickly than a large aluminum sheet with an ungalvanized steel bolt in it. (Though the effect on the aluminum can still be dramatic, as the photo below shows.)

A stainless steel screw is shown corroding an aluminum surface after six months in contact with each other at the Atmospheric Exposure Site at Kennedy Space Center on the Florida coast. (Provided by Corrosion Technology Laboratory)

But even the tiny dust is a concern, as the Automotive News article indicates. That’s why you need to invest in a curtain or separate room for body work on the F-150.

Ford puts the cost of a barrier at between $1,113 and $26,249; it’s unclear if the $26,000 figure represents putting up walls or just the Cadillac of protective shop curtains.

“The more isolation that you put in place probably it is more likely that the cross-contamination will not occur,” Marks said, though he didn’t have a specific recommendation.

Generally, he said, go with whatever the OEM tells you.

Levine also elaborated on Ford’s recommendations with the following:

“As has been recommended since aluminum hoods became standard for F-150 starting in 1997, body shops should separate steel and aluminum repair areas to avoid cross-metal contamination that could lead to corrosion. The same applies to repair tools. Aluminum and steel repair tools, even if they are identical, should be kept in separate areas.”

Despite reports to the contrary, galvanizing won’t go away with the high-strength steel and advanced high-strength steel seen as the future of the metal in fleets looking to meet fuel consumption rules, Hall said.

“It’s galvanized just like other steel,” she said.

However, the even stronger ultra high-strength steel can’t be galvanized as easily and uses an aluminum-silicon coating.

Like Automotive News, Marks noted the rush to market equipment for the F-150.

“Everybody’s out there selling curtains,” he said.

What’s interesting about all of this is that aluminum has been used in cars for years — hoods, for example — and this corrosion hasn’t been widely reported, according to Hall and Marks.

“No one’s really made a big deal about it,” Marks said. “… It’s really, really hitting the news now.”

Hall, who spent 30 years at General Motors, recalled that aluminum hoods had been used by that company for “quite a long time,” since the first half of last decade.

“I don’t remember ever hearing about corrosion issues from repair,” she said.

Different grinding equipment was used on steel and aluminum — Ford also requires dedicated aluminum tools to make its F-150 list — but both were stamped on the same line.

“Nothing else was different,” she said, with regards to protection.

But despite the lack of past dramatic aluminum-steel corrosion issues, Marks still recommended keeping the two separate to minimize variables during the collision repair process.

“In order to have a successful repair, it’s a good thing to have as many things working in your favor as possible,” he said.

More information:

“How to contain aluminum dust?”

Automotive News, June 6, 2014 (reposted Jan. 24, 2015)

“Aluminum tool vendors put the peddle to the metal”

Automotive News, Feb. 1, 2014

Featured image: Aluminum powder is shown here in this photo illustration. (Watcha/iStock/Thinkstock)