Ahead of PARTS Act hearing today, we look at proposed aftermarket auto body parts law, supporter’s argument

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Legal | Repair Operations | Technology

A House intellectual property subcommittee today will examine the collision-repair related PARTS Act.

The latest iteration of the law would prevent automakers from enforcing patents on the appearance — but not the function — of parts after only 30 months. Right now, any design patents issued by the government are good for 14-15 years.

The Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee will hear the bill, House Resolution 1057, at 2 p.m. Follow along live here. A companion bill exists in the Senate: S. 560.

“Next week the IP subcommittee will examine the PARTS Act, which reduces the number of years auto makers may sue competitors for infringing their design patents for specific car parts that are typically replaced after collisions,” Judiciary Chairman Bob Goodlatte, R-Va., said in a statement Friday. “This hearing will weigh the consequences of such a limitation to determine if the PARTS Act strikes the proper balance between protecting existing intellectual property rights under the Patent Act and creating greater competition in the automotive after-parts industry.”

H.R. 1057 and S. 560 open a striking loophole for aftermarket part manufacturers to create generic versions of OEM parts like grilles and panels in that absolutely no other industry’s design patent rights would be limited in this fashion. That means Trek or Schwinn can design-patent a bike reflector’s appearance, but General Motors can’t patent the exterior look of a taillight.

In fact, that focus is so narrow that it excludes aftermarket manufacturers and modders. That means that an overseas aftermarket manufacturer with a design patent on a sweet-looking grille can bust knock-off versions for 14 years, but Ford can’t.

It’s also highly important to note that design patents don’t actually involve the function of an item. (That’s called a utility patent.) An automaker’s design patent technically just involves the aesthetics of a part, and not any actual benefits in terms of occupant or pedestrian protection, aerodynamic function (or lack thereof, in the case of a spoiler) and fuel economy.

That said, some design-patented objects might deliver some of those functions, and that’s the concern for repairers and OEMs — and the aftermarket industry — besides the direct issues of fit, revenue and piracy. (See our Q&A with CAPA and NSF International regarding aftermarket parts for a deeper look at how certified aftermarket parts are vetted.)

While the proposed legislation has been billed as in consumers’ interest, the Consumer Federation of America public affairs director heavily involved in the bill — and appearing at the hearing today — is none other than CAPA Executive Director Jack Gillis, who has a personal stake in promoting aftermarket parts.

Burris Law IP attorney Kelly Burris; Felder’s Collision Parts owner Pat Felder; and Automotive Service Association President and Executive Director Dan Risley are also slated to testify today.

“Car repairs are often a necessary, but costly process,” Subcommittee Chairman Darrell Issa, R-Calif., said in a statement. “The PARTS Act seeks to change this by about allowing greater car-part competition resulting in lower consumer repair prices and enhanced choice. I look forward to hearing from key stakeholders about the impact of this proposal.”

For all the ink, arguments, analysis, lobbying and tax dollars spent examining the issue, it turns out aftermarket parts also don’t save very much money at all — at most $24 a year on insurance premiums — by the calculations of PARTS Act advocate Property and Casualty Insurers Association of America. So by getting a knock-off part for the second most expensive thing you own, you saved enough to buy about an extra eight days worth of coffee, based on Statista’s analysis of data from a few years ago.

Op-ed dissected

We’ve pointed out some flaws in the proposed legislation here and elsewhere. We’d also like to do so for the latest hype we’ve seen for the law, a December guest op-ed by former AARP President and CEO Bill Novelli, an economics professor, in the San Diego Union-Tribune.

With more than 30 million vehicles on the road, California is the nation’s largest car market. But if automakers have their way, the cost of repairing them could substantially increase, disproportionately affecting those on low and fixed incomes, including retirees and seniors.

That’s because auto manufacturers are seeking to use patent laws in an attempt to curb the use of quality aftermarket parts when repairing vehicles damaged by collisions often known as “fender benders.”

Automakers are exercising their rights under U.S. patent law to request design patents. It’s not a rubber-stamp; they must apply and prove that someone else doesn’t have a similar design or the look is too general to count.

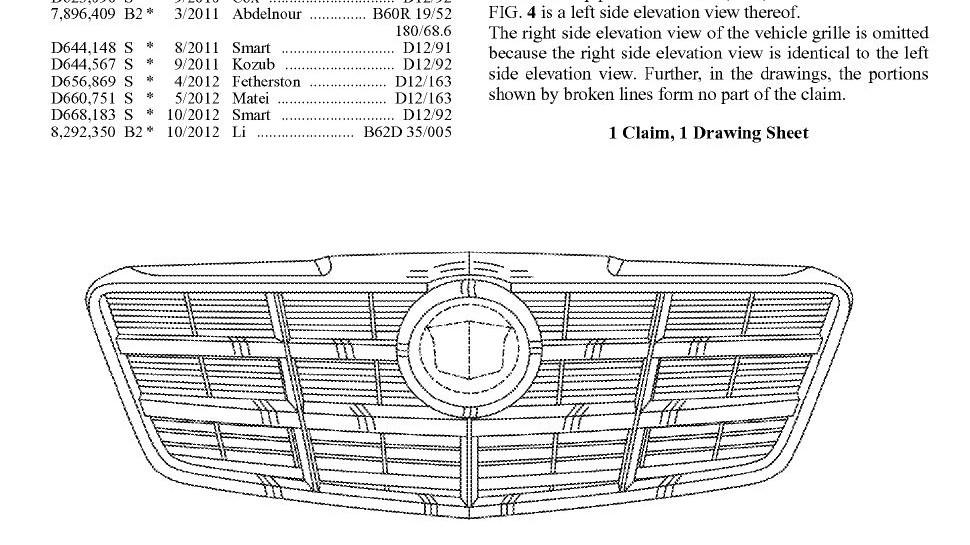

Yes, they’ve filed for more of them than in the past, which the Quality Parts Coalition says was done to keep the price of OEM parts elevated and protect a monopoly.

But if there’s evidence the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has been too lax in its design patent scrutiny in general, then your issue is with the regulatory agency, and legislation should seek to reform the patent process, not a specific industry. If it’s giving automakers and no one a pass, then that’s an oversight issue worthy of an inspector general, not a “baby with the bathwater” measure like this.

If you feel 14 years is too long to for a company to retain design patent protection, then change the law for everybody — all manufacturers and designers, whether OEM, Tier 1 or aftermarket.

Aftermarket parts are typically less expensive than those provided by automakers – or Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) — and are often used to repair and maintain the nation’s 250 million cars and trucks.

If manufacturers are successful in this effort to squeeze out the use of aftermarket parts, the cost of making necessary repairs would place new financial burdens on all hardworking Americans.

Since the hardworking Americans with collision coverage here only have to pay $24 more a year in premiums, which is less than a day’s work at minimum wage, the burden is a stretch. Or perhaps Novelli should direct his ire at insurers — advocates for the bill — why don’t they lower premiums or cut back spending on Super Bowl ads to provide all the “hardworking Americans” with OEM parts? (And how come nobody ever points out that unemployed or lazy workers deserve equal protection under the law? Just saying.)

Additionally, the parts in question are not critical to auto performance or safety. Principally, they are those used to make cosmetic repairs that include headlights, bumpers, fenders and door panels.

This is debatable. One can also wonder if vehicles are truly restored to preloss condition if the weight, metallurgy or aerodynamic properties of the part change.

Often these repairs are made to extend the life of a vehicle and provide benefits to those who simply cannot afford to buy new cars.

If you’re paying out-of-pocket, Novelli has a point. If the insurer’s paying for the repair, which is the case in 70-plus percent of repairs, then the benefit is to the insurer. They’re the ones who under the terms of a contract must restore your car to pre-loss condition. You at best saved $24 a year in premiums.

Competition is the market force that permits affordable alternatives to the more expensive OEM parts provided by automobile manufacturers.

However, if automakers are allowed to use infringement actions to curtail the use of aftermarket parts they can become a monopoly in the auto repair industry.

And that could make the cost of necessary repairs as much as 50 percent more than when quality alternative parts are used, which in many cases are actually made by the same companies that supply automakers.

The repair bill for parts might be higher — though not necessarily, if the OEM has a price-matching program. (Admittedly, a benefit of competition from the aftermarket.) But the bill for labor and other costs should be either identical — or higher if the part doesn’t fit right the first time; isn’t primed; or is of lower quality, any of which could lead to extra labor to solve the issue or storage time if the part is returned.

An Alliance of Automotive Manufacturers representative also pointed out that an OEM whose models had higher repair bills wouldn’t be as competitive as another OEM. (And insurers would know these costs and probably raise rates anyway.)

If consumers can benefit from choosing generic ibuprofen to get rid of a headache, why not ensure they will have the right to choose which headlight or bumper guard to buy when having an auto repaired?

This is the most most seriously flawed argument aftermarket advocates make. Generic drugs must be chemically identical to the original and receive Food and Drug Administration oversight. Nobody aside from two certification groups with a stake in the existence of the parts (though to their credit, they acknowledge the existence of sub-par parts) consistently checks aftermarket parts. And even aftermarket parts which can’t get NSF or CAPA certification can still be sold as suitable for cars.

Consumer choice is a legitimate point — though the aftermarket parts debate has seen some controversy already over consumers who didn’t know or didn’t see in the fine print aftermarket parts would be used — so long as it’s informed. But columns like Novelli’s do little to inform the consumer.

More information:

“Protecting consumer choice, low-cost auto repairs”

San Diego Union-Tribune guest op-ed, Dec. 9, 2015

“IP SUBCOMMITTEE TO HOLD HEARING ON PARTS ACT”

House Judiciary Committee, Jan. 29, 2016

House Judiciary Committee webcast

House Judiciary Committee

Images:

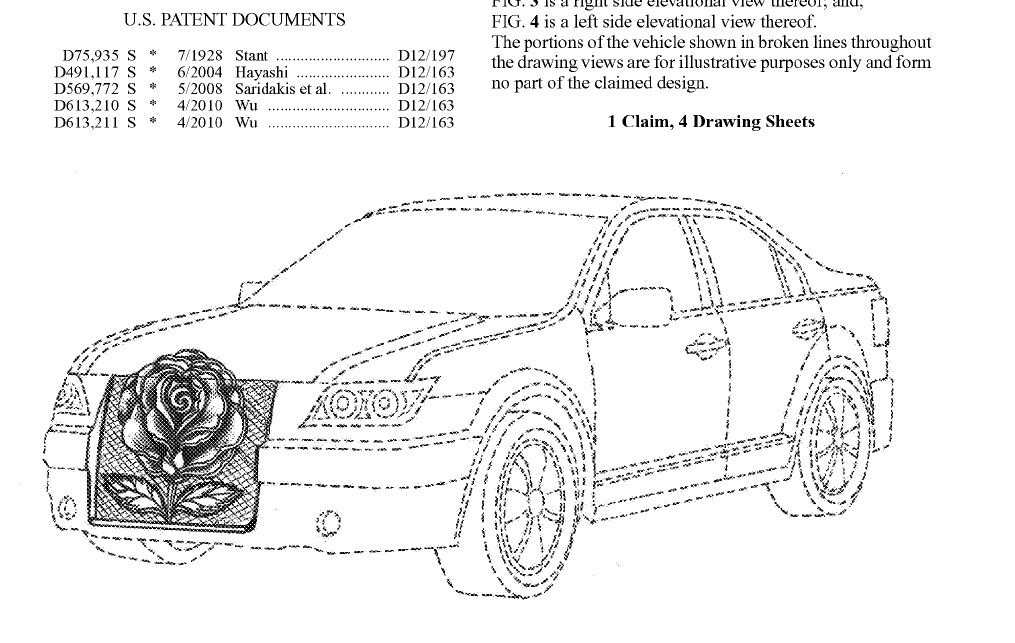

This is a 2015 design patent for a grille; it does not appear to be from an OEM. (Provided by U.S. Patent and Trademark Office)

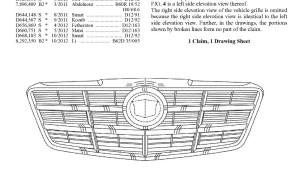

Part of a General Motors 2016 design patent for a grille is shown. Gee, do you think it’s for a Cadillac? (Provided by U.S. Patent and Trademark Office)

This chart shows the number of design patents granted OEMs in recent years. (Provided by Quality Parts Coalition)

Auto parts are shown in this graphic. (1971yes/iStock/Thinkstock)