Mitchell analyst: ‘Special materials’ article meant to ‘alert’ carriers to potential premium impact

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Insurance | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

A Mitchell analyst said that part of the impetus for his first-quarter Industry Trends Report cover story on “special materials” growth was a concern that insurers are unprepared for the greater severity such substrates bring to a claim.

“Are their actuarial departments factoring in the advent of these special materials?” study author Hans Littooy, Mitchell vice president of consulting and professional services, said in an interview earlier this month.

“I think that’s kind of why I wrote the article,” he said — to “alert” carriers this was happening.

Modeling future severity based off past performance might not be realistic given the pace of materials and other technological change. An OEM might slightly change a vehicle annually, more significantly midcycle, and completely overhaul it with a new generation every 7 years or so. (Or more rapidly: The current-gen Malibu started with the 2016 model year, replacing a short-lived generation that debuted for the 2013 model year and was a year later tweaked structurally to beat the IIHS’ small-overlap crash test.)

These types of life cycles happened in prior cars. But as Littooy pointed out, cars hadn’t changed much in materials or assembly for decades prior.

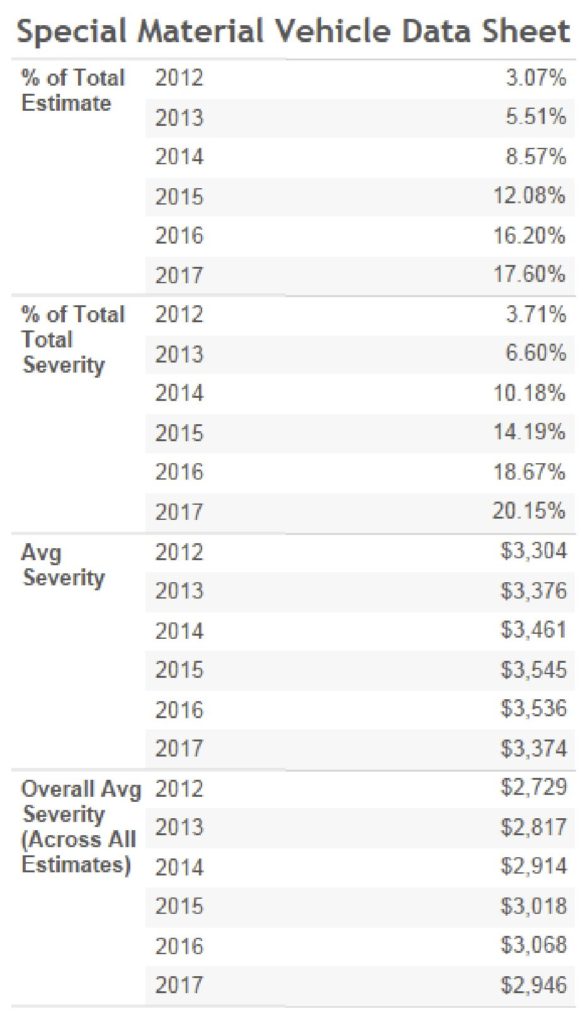

In 2012 Mitchell repair data — which reflects roughly an average model year of 2005 — only a little more than 3 percent of repairable vehicles had “special materials,” which Mitchell more or less defined as anything that wasn’t mild steel. By 2017, it’d grown to nearly 18 percent, based on Mitchell’s estimate — and we’re only up to an average 2010 model year appearing in shops.

Since then: Democratic President Barack Obama’s CAFE emissions requirements and more stringent Insurance Institute for Highway Safety crash requirements — which together might have helped touch off the aggressive lightweighting we see — didn’t come along until the actual calendar year 2012.

The aluminum Ford F-150 appeared in the 2015 model year. Two model years later, Chrysler renamed the Town & Country the Pacifica and switched from a body of mostly mild and advanced high-strength steel to one with far more ultra-high-strength steel, aluminum and even magnesium.

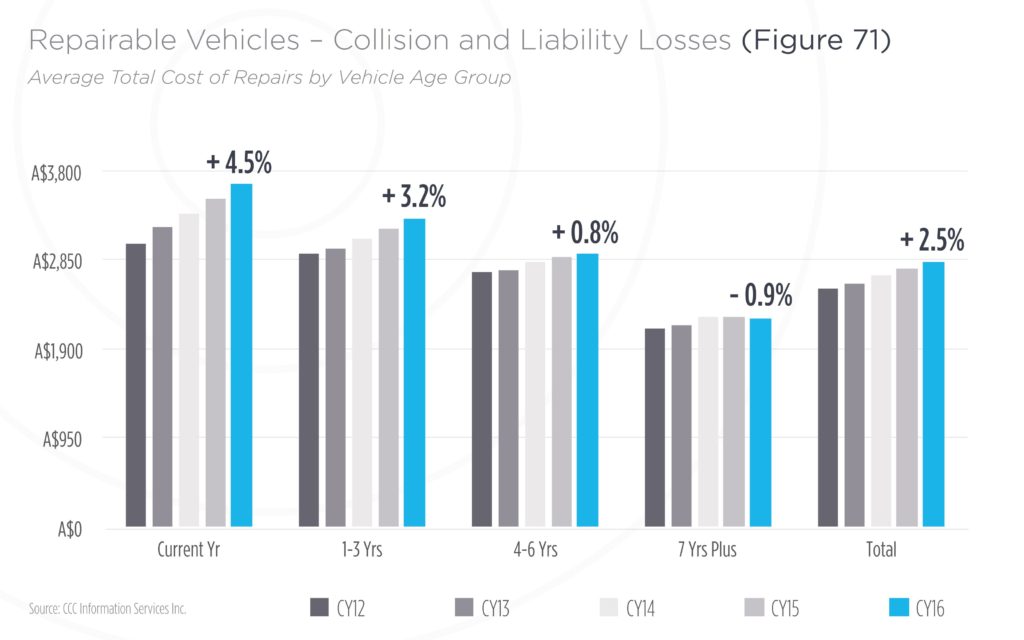

Over at CCC, which this month released its own annual “Crash Course” trends report, lead industry analyst and “Crash Course” lead author Susanna Gotsch observed that the average repair cost of new cars rose 4.5 percent in 2016 — but was down 0.9 percent for vehicles 7 years and older. It was up an average of 2.5 percent overall.

“The pace of change is faster now,” Gotsch said in an interview last month.

Littooy said “I’m sure they’re aware” at insurance companies that vehicles are changing rapidly, but did their premiums actually reflect this — or were they simply based on policyholder factors like “ZIP code and a credit score?”

“I’m not sure if the carriers are aware of this,” he said.

He said Mitchell analyzed the cost of fixing a bumper cover on a current-generation car and a last-gen one. “It was a substantial difference,” he said. (He couldn’t remember which model, but recalled it as along the lines of a Malibu.)

“I can’t say if the insurance industry heard me yet,” said Littooy, who spoke to us a few days after the release of the free Industry Trends Report.

However, Littooy said some carriers have been asking for access to Mitchell’s database of vehicle materials composition. Mitchell hasn’t yet given it out, he said.

“They’re asking,” Littooy said. “Not all of them. But a few are asking.”

Littooy said the broader question was what happens to the vehicle market when insurers do realize the costs associated with newer vehicles.

A 1960s muscle car owner himself, Littooy recalled that in the early 1970s, carriers realized that giving a 400-horsepower car to a 16-year-old driver was “not a good formula for success.”

Premiums skyrocketed, and along with the oil pricing issue in the 1970s, “that kind of killed that car market,” he said.

Littooy wondered what it meant for premiums and for OEMs when only a few shops can fix something like a Cadillac CT6? Will OEs, pressured to produce lighter, safer cars, pay more attention to repair costs or risk premiums disincentivizing buyers?

“These are questions,” Littooy said, adding that he didn’t have the answers.

Another point against relying on past severities to calculate future repair costs is that it assumes shops were fixing vehicles correctly every time. If a portion of the industry doesn’t know what it’s doing — and repair procedure usage reports, I-CAR attendance and anecdotal reinspection horror stories suggest this sadly might be the case — then data built upon those repair bills is going to be incorrectly skewed. If shops become more knowledgeable, then severity suddenly changes (likely growing) — closer to where it should have been anyway.

It seems though a smart actuary could compensate for this and avoid surprises from new materials by sitting down with repair procedure manuals and figuring out what severities would arise in various common collisions. OEMs are telling anyone with a repair procedure subscription exactly what steps have to be done when various parts are damaged. Unlike their health insurance colleagues, who can’t be certain a medical course of action will work on a unique individual, auto actuaries can assume the OEM’s steps are basically a lock to restore a mass-produced machine back to pre-loss condition (at least structurally).

We put a similar point to Gotsch last month in discussing CCC’s Crash Course results. Are carriers leveraging this OEM information for pricing? Why do the ramifications of publicly available automaker instructions seem to be a surprise?

Gotsch speculated that that just like any industry, some insurers are better than others at calculating their exposure.

“I think carriers are starting to get better at it because they have to,” she said. Those which can do more “finely tuned pricing” can be more attractive to consumers and see more growth.

She said it was interesting that if one plots out frequency and severity over time, the overall claim money paid out rises because severity has typically increased while frequency falls.

This flattened to some degree during the recession, but “I think coming out of the recession, many carriers, and many in the industry, I don’t think anticipated the larger increases that we saw,” she said.

“Private passenger auto collision, property damage, and comprehensive have experienced larger increases in severity over the last five years than frequency,” Gotsch wrote in Crash Course. “… Both the rate of auto accidents and their size or severity are rising. For the two-year period ending March 2016, loss costs overall were up 13 percent, more than 10 times the rate of inflation.

“Vehicle claim costs remain elevated and are expected to increase further in 2017 as vehicle complexity within a fleet that is growing younger continues to drive up both vehicle values and repair costs.”

Messages left Friday for the American Academy of Actuaries and American Insurance Association were not returned.

“I talked with our folks and this is not something that they have been talking with our members about, so we’ll need to pass on this one,” Property Casualty Insurers Association of America public affairs Vice President Jeff Brewer wrote in an email.

More information:

CCC, March 2017

Mitchell first-quarter 2017 Industry Trends Report

Mitchell, March 2017

Images:

A Mitchell analyst said that part of the impetus for the March 2017 Industry Trends Report cover story on “special materials” growth was a concern that insurers are unprepared for the greater severity such substrates bring to a claim. (drogatnev/iStock)

Vehicles with “special materials” — such as higher-strength steels, aluminum, magnesium and carbon fiber — have exploded from 3 percent to nearly 18 percent of Mitchell’s estimates over the past five years, the company reported in March 2017. (Provided by Mitchell)

In CCCs 2016 Crash Course trends report, data shows the average repair cost of new cars rose 4.5 percent in 2016 — but was down 0.9 percent 7 years and older and up an average of 2.5 percent overall. (Provided by CCC)

The Cadillac CT6 mixed-materials body-in-white at NACE in July 2015. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)