Calif. bill on auto body shop labor rates gets another one-sided legislative analysis

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Legal

Last year, we covered the pro-insurer analysis provided by a legislative staffer to the California Assembly Insurance Committee prior to its 13-0 approval of the disastrous Assembly Bill 1679.

Insurance Committee analyst Mark Rakich has returned with yet another questionable analysis of AB 1679’s successor, Assembly Bill 2276. The document is skeptical of auto body shops’ opposition and the California Department of Insurance regulations which would be undermined but fails to subject the insurance industry to a similar scrutiny.

Asked about the seeming one-sided nature of the document, Rakich said Thursday he wasn’t authorized to talk to the press.

“The analysis speaks for itself,” he said.

Rakich’s takes on AB 1679 and AB 2276 appear particularly flawed when compared to the far fairer AB 1679 summary produced last year by Appropriations Committee analyst Lisa Murawski.

The Insurance Committee unanimously approved the bill Wednesday, just as it did with AB 1679 in 2017.

The CDI’s regulations passed the Office of Administrative Law and became final in 2016 after years of work. For practical purposes, they took effect Feb. 28, 2017. The new rules don’t require insurers to complete labor rate surveys at all, but provide direction for those who do.

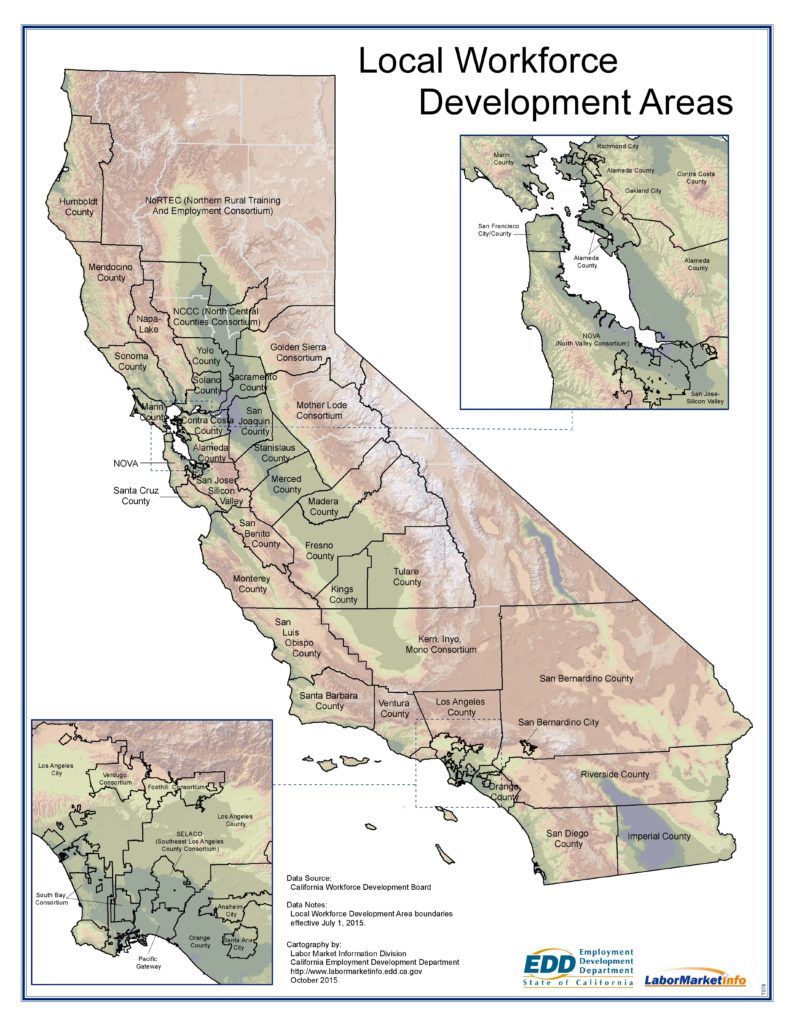

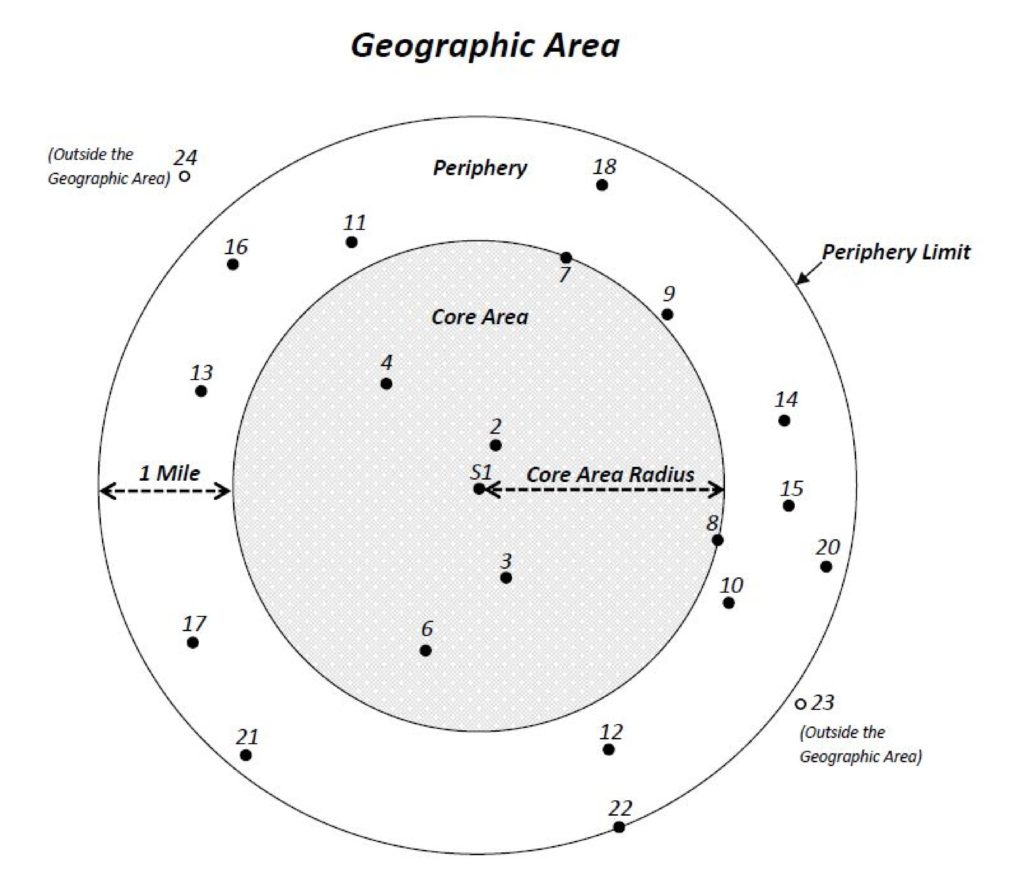

Carriers who elected to follow the proposed survey template and survey methodology defining a market area extending a mile out from a six-shop cluster could receive a “rebuttable presumption” they were acting in good faith on labor rates. As Rakich noted, other methods have apparently been deemed satisfactory since the regulations took effect Feb. 28.

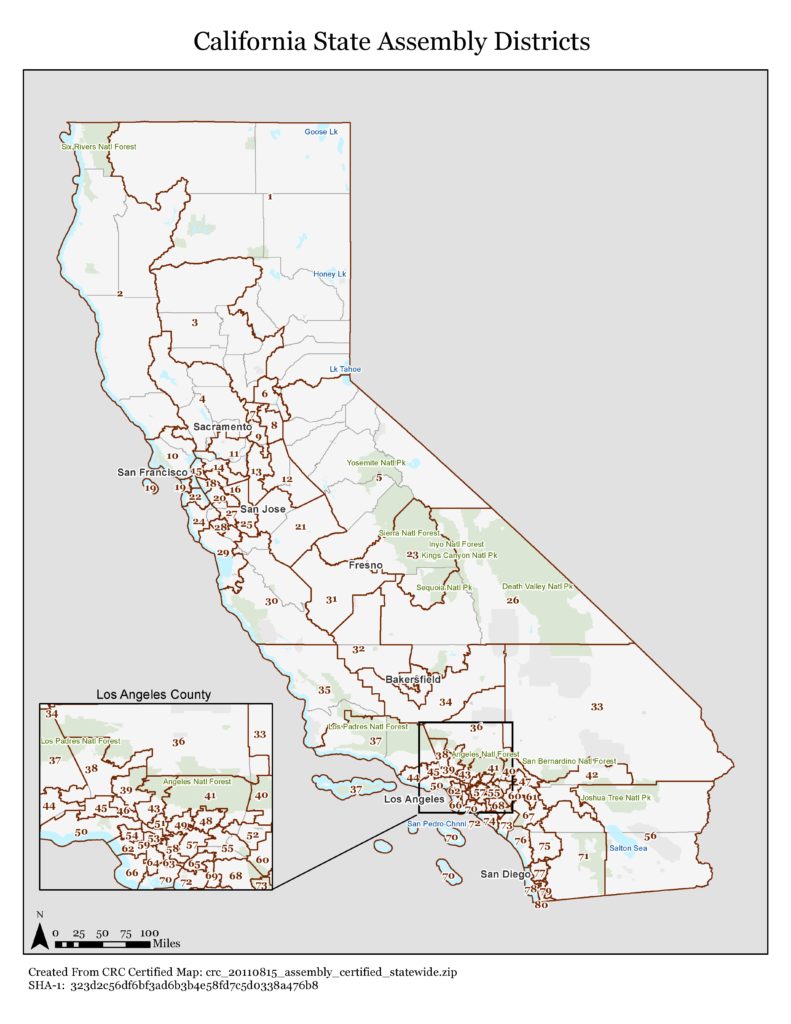

“It bears noting, however, that in the past year DOI has, in fact, accepted other methodologies,” he wrote. “… With respect to size of geographic areas, the 80 Assembly district option in the bill compares favorably from a repair shop perspective to many of the surveys actually accepted by DOI, where the number of geographic areas used by insurers typically ranges from the high 20’s to the high 30’s.”

(As the CDI was critical of large market areas during the rulemaking, we emailed their press office Wednesday seeking more details on these approved markets and methods. We have not yet received a response.)

It’s also interesting to see how Rakich just copy-and-pasted elements from his 2017 analysis of AB 1679 into the new summary, even though Assemblywoman Autumn Burke, D-Inglewood, has made some significant changes to the measure. (The California Autobody Association still opposes it because of some pretty serious flaws, but the new bill is certainly an improvement over the old one.)

Here’s some problems with Rakich’s analysis, some of which are carryovers from 2017:

Pro-‘loophole’

Rakich describes insurers’ fears that the methodology proposed by the California Department of Insurance will effectively become a mandate — something the OAL specifically shot down in 2006.

This occurs because, having stated what the agency finds acceptable, anything else is functionally unacceptable. Insurers fear that the DOI’s labor rate regulation could operate in just this manner. It bears noting, however, that in the past year DOI has, in fact, accepted other methodologies. The problem is that these regulatory decisions are not based on any law the insurers can predictably rely upon, and are subject to changing DOI regulatory discretion. This enforcement uncertainty is one of the reasons that the bill proposes an additional, statutory, survey method. But just like the DOI regulation, the bill does not propose a mandatory methodology. In fact, the bill expressly allows an insurer to use other methods for determining a prevailing auto body repair labor rate that use methods that reasonably consider market conditions in a specific geographic area. Opponents view this provision of the bill as a “loophole.” Insurers view it as recognizing that a fair payment to an auto body repair shop can be determined in a variety of ways. For those insurers that do not want the certainty of a law that establishes rules they can confidently comply with, the bill (as well as the DOI regulation) allows other approaches.

Rakich gives the opposition a single sentence, doesn’t elaborate on how big of a loophole this is, and devotes basically the rest of the paragraph to how insurers feel — ignoring the fact that bad behavior by the industry is what prompted the regulation in the first place.

This is especially problematic as whatever insurers choose to do with this loophole doesn’t appear to be subject to the reporting procedures on a typical labor rate survey.

Not only does Rakich lavish attention on insurers’ point of view, the lengthy passage also tosses off an absurd series of logical backflips explaining their position.

Insurers want alternatives to the DOI methodology:

This occurs because, having stated what the agency finds acceptable, anything else is functionally unacceptable. Insurers fear that the DOI’s labor rate regulation could operate in just this manner.

No, they want something definitive:

It bears noting, however, that in the past year DOI has, in fact, accepted other methodologies. The problem is that these regulatory decisions are not based on any law the insurers can predictably rely upon, and are subject to changing DOI regulatory discretion. This enforcement uncertainty is one of the reasons that the bill proposes an additional, statutory, survey method.

No, they want to be able to do whatever they want to do:

But just like the DOI regulation, the bill does not propose a mandatory methodology. In fact, the bill expressly allows an insurer to use other methods for determining a prevailing auto body repair labor rate that use methods that reasonably consider market conditions in a specific geographic area. Opponents view this provision of the bill as a “loophole.” Insurers view it as recognizing that a fair payment to an auto body repair shop can be determined in a variety of ways.

Turns out, the CDI’s regulations also allows them this flexibility as well after all:

For those insurers that do not want the certainty of a law that establishes rules they can confidently comply with, the bill (as well as the DOI regulation) allows other approaches.

But the biggest logical misfire here involves the notion that “these regulatory decisions are not based on any law the insurers can predictably rely upon, and are subject to changing DOI regulatory discretion” — and so the solution is a bill that “allows an insurer to use other methods for determining a prevailing auto body repair labor rate that use methods that reasonably consider market conditions in a specific geographic area.”

So who determines if those methods are “reasonably” evaluating the market? Presumably, that’d be the CDI Rakich just presented as a mercurial regulatory monster.

Size

Rakich describes the controversy over what geography should count as a local market, and presents this fairly. But he then seems to advocate for the Assembly district option:

With respect to size of geographic areas, the 80 Assembly district option in the bill compares favorably from a repair shop perspective to many of the surveys actually accepted by DOI, where the number of geographic areas used by insurers typically ranges from the high 20’s to the high 30’s.

This is an interesting point, and we’d like to hear more about the CDI’s rationale for accepting these. What’s galling here is that Rakich doesn’t critically approach the body shops and insurers’ arguments the way he does to slam body shops on other issues. This is frustrating because the bill’s geographies — even the assembly districts — are often ridiculously large and, in the case of one built around contiguous ZIP codes, prone to serious manipulation. It’s really pretty obvious who’s in the right here.

The bill allows insurers to use the precise, geocoded six-shops-plus a mile solution the CDI considers an appropriate definition of a collision repair market. But it gives them two other options: Assembly districts, or enough contiguous ZIP Codes in a Local Workforce Development area to have at least 30 shops.

The 2011 California redistricting effort sought to get as close to 465,674 people in each district as possible. Thus, some Assembly districts are huge and would create an absurdly large “market”; for example, District 1 runs from Lake Tahoe to the Oregon border. Local Workforce Development areas also can be gigantic as well.

Labor rates

Rakich mostly ripped off his argument from 2017 with regards to labor rates and fears that insurers will have to pass apocalyptic cost increases on to consumers, and it’s just as silly now as it was then. See us tear it apart here.

One point does bear further discussion:

An insurer’s labor rate survey can only use data submitted by repair shops that have responded to a survey – and there is no requirement that a repair shop respond. In addition, the insurer must use the responses of all of the shops that do respond. (Title 10, California Code of Regulations, Section 2695.81, subdivision (d), paragraphs (2) and (3).) A natural upward pressure on the calculated prevailing rate will occur as the lower price repair shops realize, which they certainly will, that by simply declining to respond to the survey, the remaining data will result in a prevailing labor rate that is higher than their current price, and which the insurer will now have to pay to all repair shops, in order to obtain the benefit of the regulation’s safe harbor.

First of all, the second half of this was wrong last year and it’s still wrong in 2018. An insurer clearly can pay the lower of the shop’s door rate or the prevailing rate under the CDI regulation.

But the notion of shops failing to respond to the survey was a fair point both years (even if we don’t agree with Rakich’s conspiracy-theory reason for them not responding), and one that could be problematic for shops as well. Fortunately, the CAA proposed an elegant solution in a letter to Burke.

“A more transparent approach is to allow a neutral third party such as the BAR (which regulates all auto body shops) to collect labor rate information from body shops when shops renew their license/registration,” California Autobody Association interim Executive Director Don Feeley (City Body and Frame) wrote. “This would allow for: a) factual labor rates being reported; b) elimination of cherry picking by insurers, c) saving insurers much or all of the cost of gathering rate data; d) consistent and reliable surveys and fewer complaints. Any costs associated with BAR collecting data could be covered by a small increase in annual fees and BAR could also charge insurers a reasonable fee for data.”

Rakich also presents examples of shops boosting their rates, though he fails to connect the dots in one example.

This upward pressure on rates is not merely theoretical. One major market share insurer conducted a labor rate survey in the past year using the criteria outlined in the regulation’s safe harbor. That survey was filed with the DOI, and available for review by the public.

So how much did rates increase? Rakich doesn’t say.

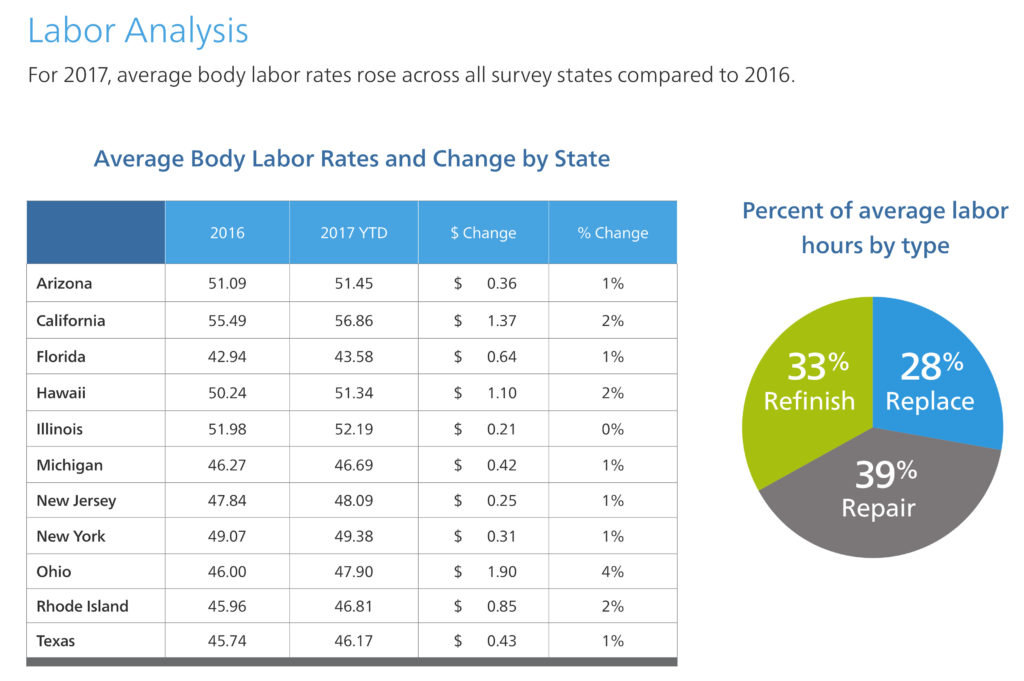

According to another major market share insurer, the results of the regulation-compliant survey would increase its vehicle repair costs by 30%. One of the primary purposes of the bill is to provide a methodology that an insurer can reliably comply with that does not have this rate inflationary tendency.

We pointed out in 2017 how silly the second sentence is. First, Rakich’s conspiracy theories of shops manipulating rates would work just as well under the scenarios proposed by the bill. Second, are shops supposed to keep the same rates through the end of time while all other normal businesses, including insurers, can adapt to inflation?

Finally, despite these tepid examples — a labor survey that proves something and an insurer’s prediction — there’s little suggest body shops are going wild with rates.

The average California auto body labor rate rose from $55.49 to $56.86 in 2017, according to the first-quarter Mitchell report. That’s a 2.4 percent increase, barely more than the 2.1 percent national inflation rate and less than the California inflation rate of 2.9 percent.

The cost of car insurance nationally increased 7.7 percent in 2017; precise data for California couldn’t be determined.

Balance billing

Rakich wrote a fair analysis on notion of balance billing in 2017, incorrectly noting that there was little evidence to support the fear that it was happening but keeping an even tone throughout the process.

According to California Department of Insurance’s statement of reasons for the regulation, balance billing was indeed happening.

“Currently, the process of using unsupported and unreliable prevailing labor rates to pay or adjust automobile insurance claims often results in unfair and unequitable claim settlements due to inconsistent and unreliable geographic areas,” the CDI wrote in 2016. “The Department received hundreds of consumer complaints alleging specific instances where consumers were forced to pay out-of-pocket costs, or shops were deprived of their reasonably charged rates, due to outdated, and unreliable surveys.

“The complaints all allege similar allegations. When the consumer took their vehicle for repair, the auto body shop billed the consumer based on the work that was done on their vehicle. When insurance covered auto body repair work, the auto body repair shop on the behalf of the consumer engaged with the insurer to settle the labor rate component of automobile insurance claim. However, the complaints alleged that the prevailing rates for many geographic areas fell well below the shop’s actual cost, as the result of unreliable geographic areas that do not accurately reflect the actual labor market, or using outdated surveys. Thus, consumers were forced to pay the difference between the prevailing rates and the actual labor rate charged by the shop or shops were deprived of their reasonably charged rates.”

But Rakich in 2018 doubled down on that assertion that balance billing wasn’t an issue despite that clear evidence to the contrary, offering a dismissive tone and skeptical counterpoint that’s absent when he presents insurers’ arguments.

There has been no evidence presented at any time to suggest balance billing has occurred or is at risk of occurring. But more fundamentally, balance billing is contrary to the economic interests of body shops. Body shops aggressively advertise for customers on the basis that the law entitles consumers to select the body shop of their choice. It is hard to imagine how a marketing strategy would work if it has the effect of stating “please select us; you have the right; but watch out, we are probably going to bill you for the balance between what the insurer pays us and what we really want to be paid.” Of course, the marketing campaign would not say this, but the market would pretty quickly operate to inform consumers that certain shops that threaten to balance bill are to be avoided. Since there is no evidence – even in the past year after this claim was publicly discussed with respect to AB 1679 – that balance billing is a genuine concern, it appears this fear is nothing more than a “Chicken Little” argument.

Where’s the “Chicken Little” comment and argument dissection whenever insurers proclaim that any reform upon them will send premiums soaring? Nowhere to be found.

Even if the CDI didn’t clearly state that complaints about balance billing existed, Rakich’s new argument for why it couldn’t happen collapses because it overlooks third-party claims.

If John Doe hits Richard Roe, Richard can take the car wherever he wants under the shop choice law. If John’s insurer refuses to pay the shop’s rates, and the shop bills Richard, Richard doesn’t need to get mad at the shop or pull his future business from it. He can sue John for the difference. The insurer is contractually obligated to indemnify John and ought to eventually cover Richard’s tab, but it’s a hassle that neither driver deserves or would have to endure with some ground rules, set by someone other than the insurer, on what a fair market rate would be.

Census and survey

One element of the survey method proposed by the bill is a requirement that an insurer randomly survey at least 30, or 30% of the, whichever is greater, licensed repair shops in the geographic region. This random sample is designed to obtain a sufficiently statistically significant data base as to produce a reliable prevailing labor rate. The DOI regulation, on the other hand, mandates that the entire population of repair shops be sent the required Standardized Labor Rate Survey. The rationale for this complete census of repair shops, and whether it is necessary or cost-effective, is unclear.

This is idiotic on multiple levels. First, insurers licensed in California presumably are getting customers statewide. Second, there’s no guarantee that the greater of “at least 30, or 30%” of shops in a market is statistically significant; while perhaps overkill, a survey of 100 percent of all shops is guaranteed to be.

In this case, the CAA’s have-the-BAR-do-it-as-part-of-licensing suggestion makes the most sense.

The CDI shouldn’t regulate how insurers treat businesses?

According to Rakich, the CDI apparently has no business regulating how insurers treat other businesses. Which sounds pretty silly, and if true, should give doctors and contractors pause.

The Unfair Practices Act requires insurers to treat both first and third party claimants in good faith. The Act says nothing about how insurers are to treat service providers that must be hired to carry out their duty to claimants. Thus, the question arises, if an insurer delivers a properly repaired vehicle to the owner of the damaged vehicle, what business is it of the DOI if the insurer drove a hard bargain with the repair shop? It is difficult to see where the DOI has authority to ensure any level of income to repair facilities, yet that appears to be one of the goals of the DOI’s regulations. The Legislature, on the other hand, has plenary authority to adopt rules that govern commerce among competing businesses.

According to the CDI, the insurer’s behavior to other businesses does matter to the agency. The CDI’s website states, “We act to ensure vibrant markets where insurers keep their promises and the health and economic security of individuals, families, and businesses are protected.”

It also says its primary role is to protect consumers and ensure insurance policies “deliver fair and equal benefits. To meet these expectations, CDI ensures that insurers are solvent, consumer complaints are addressed in a reasonable manner, and insurers and licensees play fairly in the marketplace.”

The 1868 law creating the insurance commissioner position grants him or her “power to investigate and inquire into the business of insurance transacted in this state.”

Finally, the state Supreme Court’s verdict in ACIC v. Jones supported the California Department of Insurance’s ability to develop new regulations to address bad insurer behavior, even measures not specifically called for by state statute.

Be heard: California legislator contact information can be found here and here.

Images:

The California Capitol is shown. (ChrisBoswell/iStock)

Democratic California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones speaks Aug. 12, 2016, at NACE. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)

New California Department of Insurance labor rate survey regulations, which demanded compliance by Feb. 28, suggest a market be the nearest six shops plus everyone else in a circle extending out a mile from the furthest shop. (Provided by CDI)

California’s Assembly districts as of the 2011 redistricting. (Provided by California Citizens Redistricting Commission)

A map of California’s Labor Workforce Development Areas as defined in 2015 is shown. (Provided by California Employment Development Department)

California Assemblywoman Autumn Burke appears Nov. 4, 2015, at the Lawndale City Council Chambers. (Provided by Assemblywoman Autumn Burke’s office)

The average California auto body labor rate rose from $55.49 to $56.86 in 2017, according to the first-quarter Mitchell report. That’s a 2.4 percent increase, barely more than the 2.1 percent national inflation rate and less than the California inflation rate of 2.9 percent. (Provided by Mitchell)

The California Capitol can be seen. (casch/iStock)