Appeals court rules against ABPA in aftermarket Ford hood, lamp infringement suit

By onAssociations | Business Practices | Legal | Market Trends | Technology

The Federal Court of Appeals on July 11 ruled Ford deserved design patent protection on a hood and headlight and could block ABPA members from selling imitations.

The Automotive Body Parts Association, which had sued Ford on behalf of members, said in an article Tuesday it would push for an Federal Circuit rehearing “and if necessary, in a petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court.”

Federal Appeals Circuit Judges Todd Hughes, Alvin Schall and Kara Stoll heard the ABPA v. Ford appeal by the trade group. Stoll, whose background include extensive patent experience, wrote the unanimous July 11 opinion, which was unsealed Tuesday.

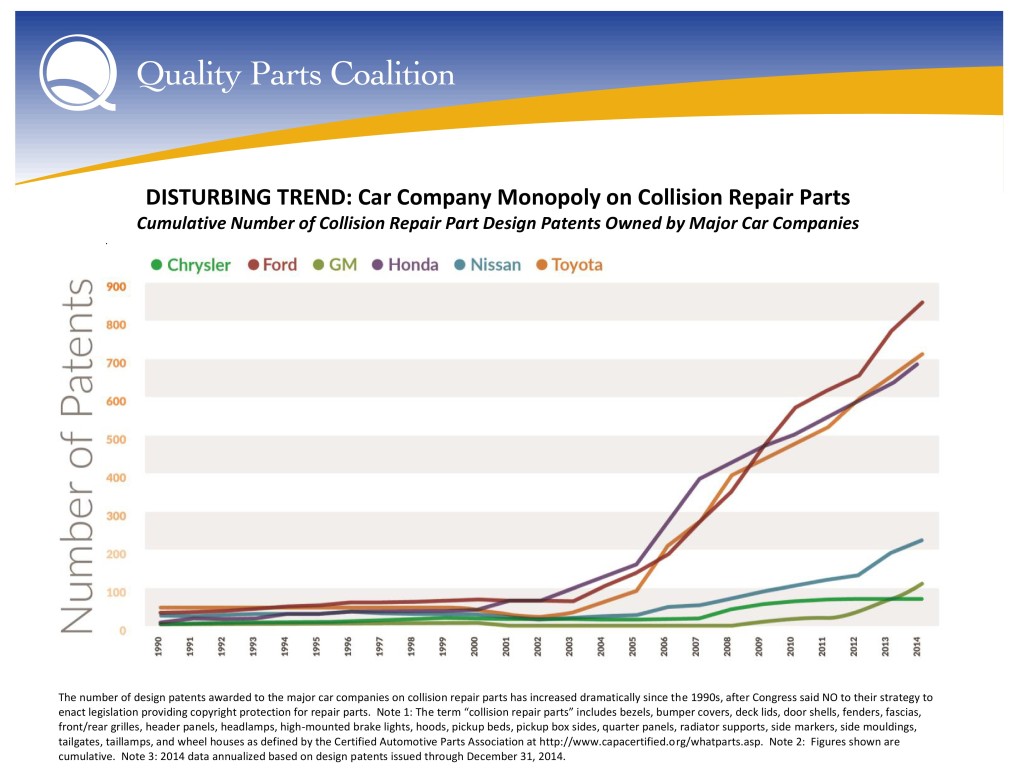

The hood and headlights appeared on 2004-08 F-150s, according to Ford.

Ironically, at the time of the ruling, both patents had already expired, as the ABPA pointed out. (The patents were issued in 2004 and 2005 for 15 years.)

The ruling could impact a related Texas case, Ford v. New World et al. The aftermarket parts vendor New World on Friday gave notice to the Northern District of Texas it would appeal its own infringement case loss to the Federal Circuit Appeals Court. Ford had accused New World and the other defendants (both of which were tied to New World) of selling auto parts infringing on Ford’s design patents online.

Northern Texas District Judge David Godbey on March 12, 2018, had approved Ford’s motion for infringement summary judgment on functionality and exhaustion. On Nov. 16, 2018, a jury ruled for Ford on 13 willful auto body part infringement counts and awarded the OEM $493,057. Godbey on March 4 added another $75,000 in prejudgment interest but let New World challenge it.

The 13 design patents in that case included a headlight, grille, hood outer and side mirror for a 2004 F-150 and two front fascias, two rear fascias, a hood, a taillight, a side mirror, a fender outer, two bumpers and a headlight for the 2005 Mustang.

Design patents

Design patents are different than utility patents. A utility patent covers an invention’s function, while a design patent merely covers how something looks.

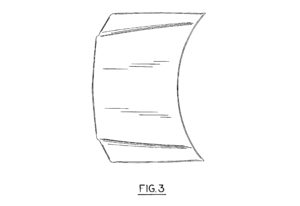

In pushing for the PARTS Act in 2015, the Quality Parts Coalition argued that some OEMs had aggressively begun to issue design patents for individual components as a means of choking off competition. The bill would have limited the length of design patents for auto parts.

“Here, we decide what types of functionality invalidate a design patent and determine whether long-standing rules of patent exhaustion and repair rights applicable to utility patents also apply to design patents,” Stoll wrote for the court. “Automotive Body Parts Association (ABPA) asks us to hold that the aesthetic appeal—rather than any mechanical or utilitarian aspect—of a patented design may render it functional. And it asks us to expand the doctrines of exhaustion and repair to recognize the “unique nature” of design patents. Both theories invite us to rewrite established law to permit ABPA to evade Ford Global Technologies, LLC’s patent rights. We decline ABPA’s invitation and affirm the district court’s summary judgment.”

U.S. Eastern District of Michigan Judge Laurie Michelson on Feb. 21, 2018, denied the ABPA’s motion for summary judgment and in fact issued summary judgement in favor of Ford. Ford, ironically, had even moved to dismiss the case as moot because it was willing to agree to never sue ABPA member New World for copying the hood and headlight in question.

However, according to Michelson, ABPA could sue on behalf of its members, which meant the case deserved a ruling.

“But this case is not between New World and Ford—it is between the ABPA and Ford. And so if there is a case or controversy between another ABPA member and Ford, the ABPA could pursue declaratory relief premised on that member’s ability to do so,” Michelson wrote.

She noted “Ford has refused to extend the covenant to all ABPA members and (National Autobody Parts Warehouse) specifically.”‘

“After reviewing the opinion, the ABPA is pleased that the Federal Circuit addressed the merits of ABPA’s arguments and did not find that the Court lacked jurisdiction based on any absence of associational standing, mootness, or patent expiration,” the ABPA wrote Tuesday. “Since this case is believed to be the first patent case involving contested associational standing in the United States, the Court’s willingness to address substantive arguments based on association standing is significant and will assist ABPA in future legal challenges.”

National Autobody Parts had asked both Ford and exclusive licensee LKQ if it could obtain a license to sell the hood and headlamp, but both turned down the distributor, according to Michelson.

“According to NAPW, manufacturers of the hood and headlamp covered by the two patents in this case have been told by Ford’s exclusive licensee, LKQ, that if they manufacture the hood and headlamp for anyone but LKQ, they would ‘be subject to patent enforcement efforts by’ Ford. Notably, these manufacturers are themselves ABPA members,” Michelson wrote. “Thus, if Ford is willing to sue those ABPA members for selling the hood and headlamp to NAPW, it seems likely that Ford would sue NAPW if it, in turn, sold the hood and headlamp to collision repair shops or vehicle owners.”

Functionality

The appeals court said a little functionality was OK in a design patent.

Citing the more than 100-year-old Gorham Manufacturing Co. v. White Supreme Court Decision, the Appeals Court rejected the ABPA’s argument that looking like the original truck parts was a functional feature.

ABPA cited no cases supporting this, and the appeals court said it couldn’t find any either.

Customers wanting to buy something because they liked the design was the whole point of a design patent, Stoll wrote for the appeals court:

We hold that, even in this context of a consumer preference for a particular design to match other parts of a whole, the aesthetic appeal of a design to consumers is inadequate to render that design functional. As the Supreme Court acknowledged almost 150 years ago, “giving certain new and original appearances to a manufactured article may enhance its salable value, [and] may enlarge the demand for it.” But regardless of the market advantage conferred by a patented appearance, competitors may not utilize a protected design during the patent’s life. To hold that designs that derive commercial value from their aesthetic appeal are functional and ineligible for protection, as ABPA asks, would gut these principles. The very “thing . . . for which [the] patent is given, is that which gives a peculiar or distinctive appearance,” its aesthetic. If customers prefer the “peculiar or distinctive appearance” of Ford’s designs over that of other designs that perform the same mechanical or utilitarian functions, that is exactly the type of market advantage “manifestly contemplate[d]” by Congress in the laws authorizing design patents.

That argument might work in trademark law, but patents were different, according to the appeals court.

“ABPA acknowledges that no court has applied “aesthetic functionality” to design patents, but it asks us to become the first,” Stoll wrote. “We decline.”

The ABPA plans to pursue this in its petition for a rehearing.

“In its opinion, the Federal Circuit held that when considering the issue of alternative designs, only mechanical and utilitarian aspects of the design are to be considered and aesthetic aspects are to be ignored,” the ABPA wrote Tuesday. “ABPA respectfully continues to believe that aesthetic considerations should be considered on the alternative design issue and is disappointed that the Federal Circuit did not address or consider ABPA’s argument that a repair design that copies the original design is invalid as functional because it does not involve a conscious design choice. ABPA will make full use of the procedural rules at the Federal Circuit that allow for a petition for panel rehearing and rehearing en banc (before the full Court) to continue making its functionality arguments, particularly since conscious design choice is the essence of the ornamentality required for a valid design patent.”

One wonders if vehicle technology advances would someday reach a point where a court or the Patent Office would rule a design too functional. For example, a body line that delivers some kind of pedestrian pedestrian functionality or makes a surface more easily detectable to another vehicle’s sensors.

However, according to the appellate court, such functionality has to be fairly absolute. Stoll noted that the ABPA missed the point of her court’s precedent Best Lock v. Ilco Unican, in which the court determined that a key blade (the part that actually works a lock’s tumblers) design patent was invalid.

“ABPA argues that only Ford’s patented designs aesthetically ‘match’ the F-150, and attempts to analogize Best Lock to the instant case,” the appeals court ruled. “But Best Lock turned on the admitted fact that no alternatively designed blade would mechanically operate the lock—not that the blade and lock were aesthetically compatible.”

Many other hoods and lights out there fit Ford trucks but looked different, Ford demonstrated, and ABPA’s witnesses agreed that “performance parts” selected by a modding consumer to fit the trucks existed, according to the court.

Stoll in a footnote also observed that the ABPA tried to claim functionality because “insurers require repair parts to use Ford’s original designs with the F-150” but provided no support.

“ABPA’s own witness explained that insurers simply pay a sum of money for repairs; they do not dictate whether a repair is even made,” she continued.

Double-dipping

A key aftermarket parts industry argument has been that OEMs shouldn’t be allowed to double-dip — a design patent should only apply to the vehicle as a whole, not individual parts of it.

The appeals court refused to set that precedent.

“ABPA asks this court to rule, as a matter of policy, that Ford’s design patents may be enforced only in the initial market for sale of the F-150, and not in the market for replacement components,” the court ruled. “ABPA argues that a market-specific rule is appropriate because customers have different concerns in different contexts. It declares that customers care about design in the initial sales market, but not when they select replacement parts. But ABPA cites no supporting facts.”

The appeals court noted “abundant record evidence regarding performance parts” meant to make the vehicle look different and said precedent worked against the association.

The ABPA still expressed happiness with part of the court’s decision here.

ABPA also is pleased that in its opinion the Federal Circuit changed an important principle in the law of design patent functionality that provides an additional opportunity to challenge the validity of design patents directed toward automotive body repair parts. Previously, it was thought that functionality only could be proven if there were no alternative designs that could perform the same mechanical function as the patented design. In the words of the Federal Circuit in the 2015 Ethicon Endo-Surgery v. Covidien case, alternative designs were “an important – if not dispositive – factor” to be considered. Other so-called Berry-Sterling factors, such as whether the design constituted the “best” design, could provide useful guidance, but according to the Federal Circuit in Ethicon, “an inquiry into whether a claimed design is primarily functional should begin with an inquiry into the existence of alternative designs.”

The ABPA opinion changes the law and makes it clear that the factor of “alternative designs” is not a dispositive factor and that other factors, such as whether the patented design is the “best” design, also can be considered on an equal basis. This is true even though there may be alternative designs that can accomplish the same mechanical function. This change in the law provides an opportunity to argue as a factual matter that a repair part design that returns the vehicle back to its original condition and appearance constitutes the “best” design for a number of reasons. ABPA members currently in litigation over design patents directed toward automotive repair parts should be able to take advantage of this new change in the law. (Emphasis ABPA’s.)

It’s unclear if the appeals court actually changed the law or merely clarified; the Ethicon case already stated “[w]e have not mandated applying any particular test,” according to a quote included in the opinion.

In the double-dipping vein, ABPA had also tried to argue exhaustion. Ford itself in oral arguments agreed that occurred when it sold a truck, according to Stoll’s opinion.

“But exhaustion attaches only to items sold by, or with the authorization of, the patentee,” the court wrote. “… ABPA’s members’ sales are not authorized by Ford; it follows that exhaustion does not protect them.”

The court refused to treat design patents differently than utility patents here and felt the Quanta Computer v. LG Supreme Court ruling cited by ABPA didn’t mean it should.

The Supreme Court “determined that the sale of a microprocessor embodying a method patent exhausts that patent,” the appeals court wrote. “It did not, however, hold that purchasers of those microprocessors could make their own, new microprocessors using the patented invention, as ABPA suggests. Far from supporting ABPA’s position, Quanta supports our reluctance to establish special rules for design patents.”

Finally, the ABPA had argued the right to repair exemption to patent law meant a company could sell an imitation part. Not if that part was patented, the appellate court ruled:

ABPA argues that purchasers of Ford’s F-150 trucks are licensed to repair those trucks using replacement parts that embody Ford’s hood and headlamp design patents. But straightforward application of long-standing case law compels the opposite conclusion. Over 150 years ago, a New Hampshire court considered facts similar to those of this case in Aiken v. Manchester Print Works. There, the patentee sold a patented knitting machine whose needles wore out on a regular basis. Though the needles were covered by a separate patent, the accused infringers argued that they could properly manufacture replacement needles to continue using the knitting machine they had purchased. The court disagreed, holding that “the needle is subject to a patent, and in making and using it they have infringed.

The New Hampshire court drew on an 1850 Supreme Court ruling that if a manufacturer didn’t patent the individual parts within a machine, then anyone could make a copy of the component. But patenting both the part and the machine prohibited an aftermarket copy of the part, the New Hampshire court ruled, according to the appeals court. Stoll wrote that the Supreme Court agreed formally with the Aiken rationale in a separate 1894 decision.

“The designs may be embodied in the hoods and headlamps that form part of the full F-150 truck or in separate hoods and headlamps,” the appeals court ruled Tuesday. “But though a sale of the F-150 truck permits the purchaser to repair the designs as applied to the specific hood and headlamps sold on the truck, the purchaser may not create new hoods and headlamps using Ford’s designs. Like the needles in Aiken, such new hoods and headlamps are subject to Ford’s design patents, and manufacturing new copies of those designs constitutes infringement.”

Again, the court declined to treat utility and design patents differently.

“Ford chose to claim designs as applied to portions of particular components, and the law permits it to do so,” Stoll wrote. “That the auto-body components covered by Ford’s patents may require replacement does not compel a special rule. Just as the patentee in Aiken could have only claimed the needles in conjunction with the knitting machine, Ford could have only claimed its design as applied to the whole truck. Unfortunately for ABPA, Ford did not do so; the designs for Ford’s hood and headlamp are covered by distinct patents, and to make and use those designs without Ford’s authorization is to infringe.”

The court also examined the language of the patents themselves to see if Ford was claiming the parts as part of the truck or separately, ruling the latter. The ABPA planned to continue to press this point and prove otherwise.

“The two design patents in question also do not claim the design of a hood, headlamp, or of an F-150, but for a portion thereof,” the ABPA wrote. “The ABPA respectfully believes the Federal Circuit provides no persuasive reasoning in its opinion for why the portion claimed cannot be considered to be embodied in the F-150 truck as well as in the hood and headlamp, which ABPA contends would lead to patent exhaustion. Indeed, both patents expressly state that the hood and headlamp are intended for attachment to a vehicle.”

More information:

Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, unsealed July 23, 2019

“Update: Automotive Body Parts Association v. Ford Global Technologies LLC”

Automotive Body Parts Association, July 23, 2019

Images:

Design patents on a 2004-08 Ford F-150 hood, pictured, and headlamp were the subject of a July 2019 Federal Circuit Appeals Court decision. (Provided by U.S. Patent and Trademark Office)

Design patents on a headlamp and hood on the 2004-08 Ford F-150 were the subject of a July 2019 Federal Circuit Appeals Court decision. (Provided by Ford via Federal Circuit Court of Appeals)

A 2004 Ford F-150 crew cab is shown. A headlamp and hood on the truck were the subject of a July 2019 Federal Circuit Appeals Court decision. (Provided by Insurance Institute for Highway Safety)

This chart shows the number of design patents granted OEMs in recent years. (Provided by Quality Parts Coalition)