Iowa Supreme Court examines when negligence so egregious incident not an ‘accident’

By onBusiness Practices | Insurance | Legal

An Iowa Supreme Court decision last week examined an interesting question: When does an employee’s behavior reach the point that an insurer’s duty to defend against an accident no longer applies?

Though the ruling in T.H.E. Insurance Company v. Stuart Glen and Stephen Booher estate relates to an amusement park’s commercial liability policy, it’s interesting to examine the alleged scenario and case discussion from the perspective of an auto body shop — and its employees.

If a technician ignores OEM procedures or is otherwise sloppy and gets sued after the car goes south in a subsequent collision, is that really an “accident” an insurer should have to cover? When would corner-cutting rise to wanton neglect? Is a bad outcome from a bad repair a probable scenario rather than a possible one?

Obviously, it depends on the language within the liability policy contract.

Polk County District Court Judge Jeanie Vaudt had ruled that the allegations regarding Adventureland Amusement Park employee Stuart Glen’s culpability in the death of co-worker Stephen Booher described gross negligence, according to the Supreme Court opinion by Justice Brent Appel.

Booher fell into the Raging River ride Glen operated in 2016 and later died from his injuries, prompting his estate and widow, Gladys, to sue Glen alleging gross negligence.

As the Supreme Court described the allegations:

Some of the allegations include Glen’s acts and omissions that allegedly occurred before the ride started: failure to check the ride before starting it, failure to assure himself that the ride assistants were not standing on any boat prior to starting the ride, and starting the ride without first obtaining the thumbs up signal from the loading assistants as required by prominently displayed instructions on the ride control board located directly in front of the ride operator. The plaintiffs also claimed that Glen admitted that he caused the assistant to topple onto the ride’s exposed conveyor belts.

Other allegations appear to focus on acts and omissions that occurred after the ride was started: failure to watch the ride for the entirety of its operation; failure to stop the ride once he became aware of the incident due to his reckless, unexpected, wanton, and premature ride start; leaving the operator’s station within the clear visual range of the fallen loading assistants without shutting down the ride; failure to engage the oversized red “E-Stop Aux” knob located immediately in front of him after he became aware that the loading assistants were down and the ride was still running; failure to key the ride to the off position after becoming aware that the loading assistants had been jerked off their feet due to the premature start of the ride; failure to stop the ride and leaving his station, although he could easily observe that Booher had been knocked down and his head and body were brought into continuous contact with that sidewall; stopping the ride only after several ride patrons repeatedly yelled at him to “stop the ride”; and failure to consider Booher’s injury, once he was knocked down, as serious.

Finally, several allegations do not have an explicit temporal component. For example, the petition claimed Glen’s gross negligence arose from his failure to be on guard and his failure to understand his role in responding to the incident.

Glen in a 2017 court filing denied the allegations and said that he “inadvertently advanced a raft resulting in injury.”

“He’s admitted he made a mistake,” Glen’s lawyer Guy Cook of Grefe Sidney Law Firm said Wednesday, calling Glen “heartbroken” by what happened. He said no park customers were ever at risk.

But it was “just that” — a mistake, an accident, Cook said. “It was not gross negligence,” he said.

The Boohers didn’t sue Adventureland; under Iowa code, on-the-job injuries or fatalities must go through the workman’s compensation system.

Cook called Adventureland “very generous” to the Boohers and said it paid them under the the workman’s comp system.

“That would be the end of the story,” Cook said. However, Iowa Code still permits lawsuits against co-workers who commit gross negligence — something he said the park and Glen deny happened.

It was merely a “tragic accident,” Cook said.

Adventureland has focused on safety since it started, according to Cook. “It remains the No. 1 focus,” he said.

The district court held the alleged gross negligence would have occurred once Glen alleged realized Booher had fallen into the ride but didn’t stop it. Vaudt granted summary judgment on behalf of T.H.E. Insurance Company, ruling its policy meant it didn’t have to cover allegations of negligence that rose above the threshold for an accident.

“The district court reasoned that the Boohers’ claim of gross negligence was not covered under the CGL policy. The district court noted that under the CGL policy, ‘bodily injury’ must arise from an ‘occurrence,'” Appel’s Supreme Court opinion states. “Under the CGL policy, an ‘occurrence’ is ‘an accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same general harmful conditions.’ Applying caselaw, the district court reasoned, an ‘accident’ is an ‘unexpected and unintended “occurrence.”‘ But the injuries that occurred after Glen realized he had fallen in were not unexpected and unintended but were the natural and expected result of Glen’s conscious action in not stopping the ride. As a result, there was no coverage under the CGL policy because the Boohers’ gross negligence claim was not an ‘accident’ and therefore not an ‘occurrence’ under the policy. Using similar reasoning, the district court also held that there was no coverage of the Boohers’ claim under an exclusion in the policy that provided that injury that is expected or intended from the standpoint of the insured is excluded from coverage.”

Section I of Adventureland’s commercial general liability policy says T.H.E. Insurance Company will pay “bodily injury” if it’s from an “occurrence” — and it excludes any bodily injury “expected or intended from the standpoint of the insured. Occurrence is defined as “an accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same harmful conditions.”

Section II says employees are covered by the park’s policy but not for bodily injury or “personal or advertising injury.” However, an “Employee v. Employee Bodily Injury Liability” multiplex liability endorsement restores bodily injury to the coverage.

The Boohers case is muddied by the 2015 version of Iowa Code 85.20. The worker’s compensation law prevents employees from suing a co-worker over occupational injuries unless it is “caused by the other employee’s gross negligence amounting to such lack of care as to amount to wanton neglect for the safety of another.”

T.H.E. Insurance argued that the Boohers alleging gross negligence under the the Iowa Code 85.20 threshold meant the incident wasn’t an accident. Ergo, it didn’t have to cover it.

“Or, put differently, does the requirement in section I that the injury arise out of an ‘accident’ foreclose the possibility of coverage for any claim that arises to ‘gross negligence’ as the term is used in Iowa Code section 85.20?” Appel wrote in the Supreme Court opinion.

Appel said prior Iowa case law holds that a result is “an unexpected and unintended ‘occurrence’ so long as the insured does not expect or intend both it and some injury,” quoting the 1988 First Newton National Bank v. General Casualty Company of Wisconsin decision. (Emphasis original.)

In Weber v. IMT Insurance, the Iowa Supreme Court defined an “expected” incident as a situation where a party knew or should have known a “substantial probability” existed something bad would happen. The Weber court defined a “substantial probability” as a situation where “indications must be strong enough to alert a reasonably prudent man not only to the possibility of the results occurring but the indications also must be sufficient to forewarn him that the results are highly likely to occur,” quoting the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals City of Carter Lake v. Aetna decision.

In Thompson v. Bohlken, Iowa case law defines “gross negligence” under Iowa Code 85.20 as something that goes 3-for-3 on “(1) knowledge of the peril to be apprehended; (2) knowledge that injury is a probable, as opposed to a possible, result of the danger; and (3) a conscious failure to avoid the peril.” “Probable” means “more likely than not,” under Henrich v. Lorenz.

Iowa Code 85.20 defined gross negligence as “wanton neglect for the safety of another.” The Thompson case defined “wanton neglect” as a situation where someone is indifferent to whether someone else will be hurt.

“Wantonness is said to be less blameworthy than an intentional wrong only in that instead of affirmatively wishing to injure another, the actor is merely willing to do so,” the Thompson court held.

It’s important to note that Supreme Court didn’t rule on whether the incident constituted an accident or gross negligence.

Rather, it merely determined that some gross negligence could theoretically still be considered an accident under the terms of the T.H.E. policy, a scenario Cook called a “narrow category.” Thus, the Boohers deserved a shot to pursue their case and automatic summary judgment on behalf of T.H.E. was incorrect, the Supreme Court ruled.

“From the above analysis, it appears that a coemployee may act in a fashion that meets the definition of ‘gross negligence’ when an injury is more probable than not and that such conduct might not be outside the scope of the term ‘accident’ in the CGL policy. It is possible that a factfinder could find that a coemployee acted without intent to harm and with the expectation that an injury was more likely than not, but not with the expectation that the injury was highly likely or substantially certain to result. In other words, some, but not all, acts of gross negligence may not be accidents. … It is possible for a plaintiff to thread the needle by convincing a factfinder that acts or omissions of a coemployee gave rise to an expectation that an injury was more likely than not to occur, and thus amounts to gross negligence, but was not ‘highly likely’ and therefore outside of coverage for accidents.

“Here, the allegations are sufficient to permit the plaintiff to attempt to sail between the rocks of immunity established by Iowa Code section 85.20 and the shoals of a coverage defense under Article I of the CGL policy. The plaintiff alleges a long laundry list of alleged acts and omissions of Glen. Some occurred before the ride began, and others after Booher was thrown into the ride. At this early stage of the proceeding, based on the broad nature of the pleadings, we cannot say there is no possibility that Booher may not be able to convince a factfinder that he has a claim that amounts to gross negligence but is within the scope of the coverage of the CGL policy.”

For body shop employers and employees, the lesson of all of this is that it’d be a good idea to examine the potential consequences of one’s behavior and what liability coverage exists for it.

Images:

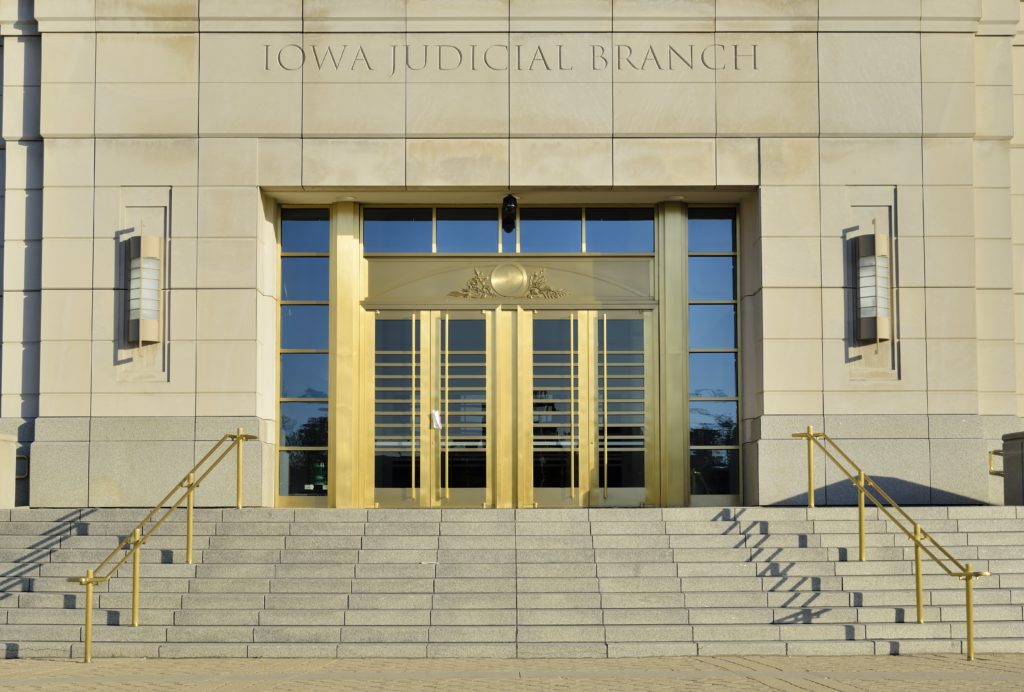

The Iowa Supreme Court is seen June 28, 2013. (RiverNorthPhotography/iStock)

The Iowa Supreme Court is seen. (RiverNorthPhotography/iStock)