AkzoNobel offers shops ideas to counter insurer rate, ‘cost of doing business’ assertions

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Insurance | Legal | Market Trends

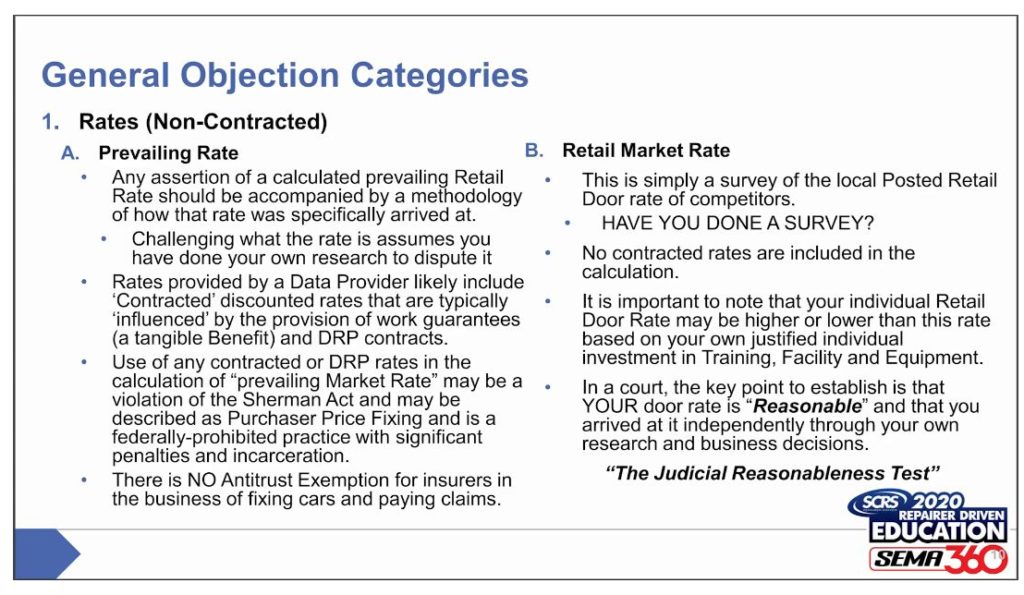

Collision repairers should develop their own market survey of retail door rates to successfully counter insurer objections to their labor rate, an AkzoNobel industry consultant advised in a virtual Repairer Driven Education course out now.

AkzoNobel senior services consultant Tim Ronak also discussed how a repairer might have to charge a higher rate just to break even on equipment or OEM certification expenses and explained how GAAP could debunk an insurer’s “cost of doing business” assertion.

Ronak’s “Overcoming Insurer Objections to Payment for Needed Repair Procedures” was among the five educational sessions the Society of Repair Specialists posted in conjunction with this week’s virtual SEMA360 show.

Other batches of courses in the series are slated to be released through the rest of the week. If you were too busy to catch Ronak’s session or any of the others available Monday, don’t worry. The entire week of RDE courses will be replayable on-demand through Aug. 31, 2021.

One session on the “BOT” and DEG tools is available for free and accessible now. The rest of the regular RDE courses are $75 each, and the OEM Collision Repair Technology summit coming later in the week is $150. A full-series pass is available for $375.

Labor rates and surveys

Ronak mentioned seeing a recent insurance policy declaring the carrier would pay the rate produced by a labor rate survey “defined by us.” However, the survey is closed and not up for review or “substantiation,” he said.

Challenging an insurer’s declaration of a prevailing rate requires a shop to have done its own research. In many cases, repairers haven’t, he said.

Information providers do make labor rate data available. However, those statistics typically include contractually discounted rates, Ronak said. (For example, rates a shop has agreed to as part of a direct repair program.)

CCC, for example, has made it clear: “CCC does not conduct labor rate surveys or report on prevailing street rates.” The benchmark data it provides aren’t the actual market rates.

Ronak said he recommends shops conduct their own survey of competitors’ retail posted door rates. This might take the form of a “mystery shop” to assess the market, he indicated.

The retail door rate might vary between shops, he said. One repairer might lack OEM certifications. Another might be spending $20,000-$30,000 a year to maintain them, he said.

Ronak explained what this might mean for the repairer’s hourly bill.

A typical technician is available for about 2,100 hours a year, Ronak estimated. (Fifty-two 40-hour work weeks comes out to 2,080 work-hours in a year.) If that tech works at a 150 percent efficiency rate, the owner is billing 3,100-3,200 hours off them, he estimated. (1.5 times 2,080 is 3,120 hours.)

He gave the example of a shop with a single 3,200-hour technician and a $32,000 annual OEM certification bill.

The shop owner would have to charge an extra $10 an hour just to break even, Ronak said. “That’s not (making) more money on it,” he said. “That’s just to recoup your money.”

The same thinking might apply to expenses like a new frame machine or welder, Ronak said.

Ronak also pointed out that it might be “problematic” from an antitrust perspective for closed contract negotiations between two parties to result in payment being limited to an “unencumbered third party.” There’s a misconception that antitrust laws don’t apply to insurers, but it’s merely a limited exemption granting new insurers the ability to see claims history data, he said.

“They have no exemption” in claims processing or payment, he said. He said that as far as he knew, such a carve-out “just doesn’t exist.”

Should a dispute over labor rates wind up in court, a shop will face what can be described as a “reasonableness test,” according to Ronak.

“There is no specific amount in a court,” Ronak said. Instead, the matter rests on what a “reasonable person” would think, he said. Would such a person think it appropriate that a shop with a significant OEM certification investment charged more?

GAAP and ‘cost of doing business’

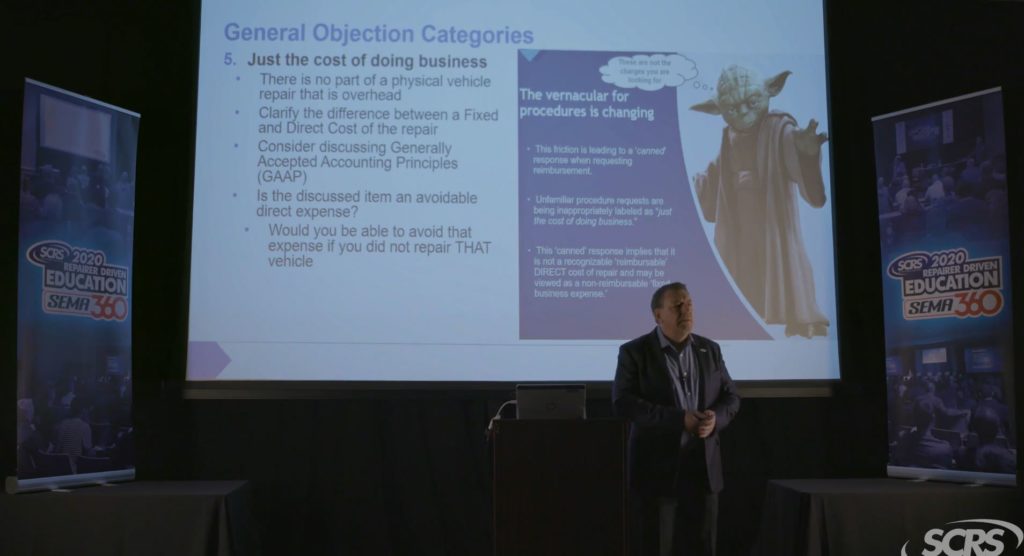

Ronak also had a solution to shops who bill for a charge only to have the insurer reject it as a “cost of doing business.” He called such a claim a “Jedi mind trick” and an assertion insurers might resort to when they don’t understand what a particular operation is.

Harkening back to his speech before the 2019 Repairer Driven Education IDEAS Collide, Ronak said in Monday’s course that shops could respond using generally accepted accounting practices, also known as “GAAP.”

GAAP involves a set of accounting rules businesses — including publicly traded insurers — all agree to follow, he said, citing Investopedia. This allows consistency and transparency for observers examining the books of businesses within the same industry or different sectors, he said.

GAAP includes both overhead and direct costs, Ronak said. Overhead costs don’t increase or decrease with sales and might include items like salaries and rent, he said. These are often described as unavoidable fixed expenses, he said.

“These are the fixed expenses that you have even if nobody shows up,” he said.

He said COVID-19 provided an “real example” of overhead: Companies still owed on leases, energy and utilities even though handing “zero productive work.”

Direct costs are variable expenses tied to the specific output of goods and services.

‘There’re going to move up and down as your output increases and decreases,” Ronak said.

He offered the example of a shop’s parts and materials spending, which would increase with the number of cars the repairer fixed. Costs like productive labor, calibrations and hazardous waste removal wouldn’t arise if you weren’t fixing a particular vehicle, he said.

“This is a key point,” Ronak said. “… It allows you to have a test.”

Ronak said the test would be to ask “Is it an avoidable cost?” Ask that of a charge an insurer claims is a cost of doing business, he said. Could you avoid a particular charge if you didn’t fix that vehicle? “That’s the test.”

If the answer is yes, then the amount is truly a direct cost associated with the individual repair. It’s not a cost of doing business.

Ronak also warned against insurers offering “cost-shifting”: Refusing to pay one charge but offering to add more labor on another operation.

“That’s just illegal,” he said. “That’s fraud.”

More information:

“Overcoming Insurer Objections to Payment for Needed Repair Procedures”

Society of Collision Repair Specialists, Nov. 2, 2020

SCRS Repairer Driven Education series website

Images:

AkzoNobel senior services consultant Tim Ronak in a virtual SCRS Repairer Driven Education course posted Nov. 2, 2020, explained how Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”) could debunk an insurer’s “cost of doing business” assertion about a particular charge. (Screenshot from Society of Collision Repair Specialists video)

AkzoNobel senior services consultant Tim Ronak in a virtual SCRS Repairer Driven Education course posted Nov. 2, 2020, encouraged collision repairers to perform their own door rate surveys of their market. (Screenshot from Society of Collision Repair Specialists video)