NTSB says failure to follow OEM procedures led to $2.2M ship-pier collision

By onAnnouncements | Education | Legal | Repair Operations | Technology

The recent conclusion of an investigation in a different transportation industry offers auto body shops a reminder of the need to adhere to OEM procedures.

The National Transportation Safety Board this spring said failure to follow manufacturer service instructions led the Atlantic Huron to strike a Michigan pier in 2020. No one was injured in the 6.8-knot (about 7.8 mph) collision — but the shipping vessel suffered more than $1.63 million in damage, and the pier’s was calculated at $573,000.

The whole $2.2 million mess is sort of one of those for-want-of-a-nail situations, according to the NTSB. The agency traced the summer 2020 incident involving the 736-foot ship back to a single set screw installed without the OEM-required thread-locking fluid.

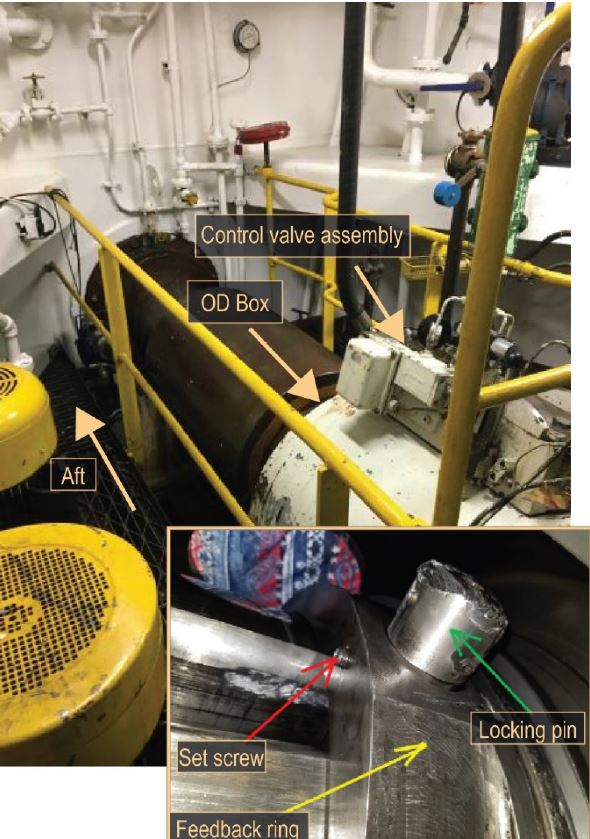

“The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the contact between the Atlantic Huron and the west center pier at Soo Locks was not following the manufacturer’s requirement to use thread-locking fluid during installation of the feedback ring locking pin set screw on the vessel’s controllable pitch propeller system, which led to the failure of the controllable pitch propeller’s oil distribution box,” the agency wrote in an April 13 report.

The NTSB said the need to apply the fluid “was clearly indicated on system schematics.”

Prior to the collision, the Atlantic Huron had sailed across Lake Superior and planned to take the Soo Locks through the Saint Mary’s River on its way to a final destination on Lake Huron. Housed in Michigan, the locks help ships travel between the U.S. and Canadian sides of the Saint Mary’s River.

The captain had planned to land the ship at a west center pier and then head up the pier wall to the locks. While attempting to slow the Atlantic Huron’s speed, he noticed the central propeller pitch indicator bounced between indicating the ship was going full ahead and full astern.

“He also received a pitch differential, or wrong-way, alarm, indicating that the requested propeller pitch from the helm station did not match the propeller’s actual pitch,” the NTSB wrote.

The ship began to travel forward faster despite the controls declaring it should have been reversing at full speed.

The chief engineer and engineer on watch went to check the actual propeller and see if they needed to adjust it manually. The central propeller pitch control valve assembly sits atop the propeller shaft’s oil distribution box, which is kept from rotating by a locking pin known as a “torque stay.” However, the engineer on watch had observed the oil distribution box shifting when first called by the captain, and the chief engineer found the part had

The engineer on watch had noticed the oil distribution box shifting back and forth when initially called by the captain. The chief engineer found the part “had rotated on the drive shaft and was no longer retained by the torque stay.”

The ship kept picking up speed, and as he hadn’t heard from the engineers yet, the captain started dropping anchors to slow down the boat. He didn’t immediately hit the emergency stop, but when the chief engineer reported the OD box’s failure, the captain approved shutting off the engine. The Atlantic Huron still wound up running into the pier.

The Atlantic Huron’s OD box had been repaired just days earlier in late June 2020 to fix what was believed to be a worn torque stay. The ship was inspected and viewed good to go through April 2021, when the clearance between the torque stay and hole needed to be addressed.

The June repair was correct, according to the NTSB. An underlying issue lurked inside the oil distribution box — but the team should not have been expected to have dug that deep and disassembled it, according to the agency.

“The damage to the OD box feedback mechanism that occurred during a previous voyage on June 26 likely was caused by the same underlying mechanical issue that eventually resulted in the total failure of the unit on July 5, the NTSB wrote. “However, since the damage from the initial incident was not severe, and the repairs that were made alleviated the problem, it is understandable that the technicians and shipboard engineers did not discover the underlying problem, since repairs did not require disassembly of the OD box. Because the repairs were minor, and a successful sea trial was conducted under the supervision of a class surveyor, the vessel’s crew and CSL management justifiably believed that the CPP and OD box systems were operating properly prior to the accident.”

This time, it wasn’t a situation where “the last one to touch the car (or ship) owns it.” Still, the NTSB report ought to also serve as a reminder of that adage just the same. Work somebody else had allegedly done led to the NTSB scrutinizing those June repairers, which probably isn’t a fun experience even when the party investigated is cleared.

The OD box’s manufacturer came to the scene.

“Upon disassembly, ‘severe damage’ to the unit’s valve block assembly was discovered, including the feedback arm,” the NTSB wrote. “… After removing the feedback arm, the technician discovered that the pin holding the feedback ring in place had backed out and contacted the arm, damaging both. Further investigation found that the set screw designed to hold the pin in place had also backed out.”

The NTSB’s report doesn’t assign any blame to the manufactuer. It also says the OEM told technicians how to avoid this issue in its repair procedures. (Which is reminiscent of the Seebachan v. John Eagle case: Attorney Todd Tracy had originally attempted to sue Honda but ultimately went after the body shop after evidence arose that Honda instructions weren’t followed.)

“The OD box manufacturer required that this set screw be installed using thread-locking fluid to prevent it from backing out,” the NTSB wrote. “Thread-locking fluid is an adhesive applied to the threads of fasteners such as screws and bolts to prevent loosening, leakage, and corrosion. Inspection of the set screw by the technician revealed that it was ‘not damaged’ and that there was ‘no evidence’ of thread-locking fluid having been applied. Vessel maintenance records indicated that the last time the feedback ring pin set screw had been removed and reinstalled was in 2016 during maintenance to the vessel’s tail shaft. Investigators could not determine if thread-locking fluid had been applied to the set screw at that time.”

Note that the allegedly incorrect maintenance work might have occurred four years before the actual collision. This ought to also be a reminder to body shops too: Just because the customer didn’t bring back the vehicle in the short term doesn’t mean you fixed it right.

The ship’s owner CSL determined that “confirmed that the manner in which the OD box and control valve assembly failed would have caused hydraulic fluid to be inadvertently directed, producing a full ahead pitch on the propeller blades when an astern pitch was ordered,” the NTSB wrote.

The NTSB said ships should add procedures in place to deal with emergencies like this. “After the accident, CSL stated that they were currently reviewing their SMS to identify operations for which ship-specific contingency plans needed to be developed for emergency preparedness,” the agency wrote.

CSL did not return requests for comment.

V.Group, the other entity the NTSB associated with the Atlantic Huron, said it had no role in the vehicle’s maintenance in question.

“I’ve checked internally and can categorically confirm that V.Group does not manage the vessel in question – CSL took management of the fleet in-house several years ago,” spokeswoman Ruth Shearn (RMS) wrote in an email Wednesday.

More information:

NTSB, April 13, 2021

Images:

The Atlantic Huron is shown following its collision with a pier on the Soo Locks. (Provided by U.S. Coast Guard)

Damage to a Soo Locks pier following being struck by the Atlantic Huron on July 5, 2020. (Provided by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.)

The Atlantic Huron’s oil distribution box and the set screw tied to a backed-out locking pin within the box are shown after the ship’s July 5, 2020, collision with a Soo Locks pier, according to the National Transportation Safety Board. The locking pin holds the feedback ring, according to the NTSB. (Provided by Coast Guard, CSL)