AAI, AG provide differing interpretations of terms in Massachusetts’ contested ‘right to repair’ law

By onAnnouncements | Legal | Technology

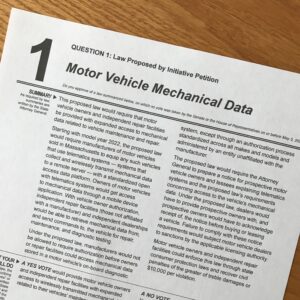

The parties in the federal lawsuit challenging the Massachusetts right-to-repair legislation approved by voters in 2020 are in disagreement over the meanings of half of the key terms written into the law, according to a legal document filed jointly on Friday.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation (AAI), representing automakers, and Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey told Judge Douglas Woodlock that they are in complete agreement on the meanings of just three of 16 terms in sections 2 and 3 of the Data Access Law: “motor vehicle,” “telematics system,” and “platform.”

In five cases, they agree on definitions, but with disclaimers. And in eight cases, which involving some of AAI’s major objections to the law, they are in disagreement, the two sides say in their 17-page brief.

Woodlock had given the parties until Friday to file the document, as he prepares to issue a ruling in the closely watched case. His Sept. 14 order directs AAI and Healey to provide “full briefing by the parties separately submitted regarding the grounds textual and legal for their respective positions.”

The disagreements suggest that the parties remain far apart on the central questions of whether adhering to the law will expose motorists to cybersecurity risks, and how long it might take OEMs to implement such a data-sharing system.

Section 2 of the Data Access Law provides that:

“[O]wners’ and independent repair facilities’ access to vehicle on-board diagnostic systems shall be standardized and not require any authorization by the manufacturer, directly or indirectly, unless that authorization system for access to vehicle networks and their on-board diagnostic systems is standardized across all makes and models sold in the Commonwealth and is administered by an entity unaffiliated with a manufacturer.”

Section 3 states,

“Commencing in model year 2022 and thereafter a manufacturer of motor vehicles sold in the Commonwealth, including heavy duty vehicles having a gross vehicle weight rating of more than 14,000 pounds, that utilizes a telematics system shall be required to equip such vehicles with an inter-operable, standardized and open access platform across all of the manufacturer’s makes and models. Such platform shall be capable of securely communicating all mechanical data emanating directly from the motor vehicle via direct data connection to the platform. Such platform shall be directly accessible by the owner of the vehicle through a mobile-based application and, upon the authorization of the vehicle owner, all mechanical data shall be directly accessible by an independent repair facility or a class 1 dealer licensed pursuant to section 58 of chapter 140 limited to the time to complete the repair or for a period of time agreed to by the vehicle owner for the purposes of maintaining, diagnosing and repairing the motor vehicle. Access shall include the ability to send commands to in-vehicle components if needed for purposes of maintenance, diagnostics and repair.”

In its interpretation of “vehicle networks,” “on-board diagnostic system” and “access” in Section 2, AAI raises concerns about cybersecurity risks it believes would result from enforcement of the law as written.

“…Auto Innovators understands that the proponents of the Data Access Law envisioned that access includes the ability to send commands to the vehicle,” AAI said. “Indeed, even ‘reading’ data requires sending such commands. Therefore, taken together, ‘access to vehicle networks and their on-board diagnostic systems’ means the ability to read and send commands to vehicles’ electronic networks and internal computer systems.”

“…[I]n any event compliance with the statute as interpreted in this way—taken together with the statute’s other requirements—would still take years to accomplish,” AAI said.

Healey countered that “the evidence at trial established that ‘access to vehicle networks and their on-board diagnostic systems’ can be provided in a way that does not compromise cybersecurity and which can be implemented in a timely manner.”

Though the parties agree on the term “standardized,” they disagree on its interpretation. Healey’s position is that the term, as used in Section 2 “not limited to the makes and models of a particular manufacturer, though the requirement in Section 3 is limited.

AAI argues that standardizing a system “across specific OEMs’ makes and models” might help OEM’s ability to create authorization systems that would reduce the loss of cybersecurity protections, though creating such standardization “will take years to accomplish.”

Healey and AAI also disagree over the OEM’s ability to comply with the law’s requirement that the “authorization system” must be administered by “an entity unaffiliated with a manufacturer.”

“[I]f the relevant ‘authorization system’ must be ‘standardized’ across all OEMs and administered by a single entity unaffiliated with any manufacturer, it will take years to develop and implement such an entity, as the entire auto industry will need to agree on the form, structure, and function of such an entity (with input not only from OEMs, but also other industry players and government regulators),” AAI said. It cautioned that “creating a single entity responsible for authorization may facilitate intrusions into multiple manufacturers’ vehicles at once. This would increase cybersecurity attack surface and risk exponentially.”

Healey maintains that the trial evidence “established that ‘an entity unaffiliated with a manufacturer’ can be created without compromising the security or integrity of vehicle networks or requiring the removal of access controls,” and that the use of such entities “is common and well-established in other industries, such as internet web browsers.

“The trial evidence further established that such an unaffiliated entity can be readily created, but the OEMs have refused to work with others in the auto industry to put together such an entity,” Healey wrote.

Healey and AAI similarly disagreed with terms used in Section 3, with AAI arguing that compliance could reduce cybersecurity and take the OEMs years to accomplish, and Healey arguing that trial evidence proved otherwise.

“The trial evidence established at least two potential methods which a given OEM might equip its vehicles with an interoperable platform: utilizing a dongle plugged into the J-1962 port as the diagnostic platform, or designing a fully telematic diagnostic platform contained on the vehicle,” Healey wrote.

She reiterated the state’s claim that automakers could comply with the law simply by deactivating the telematics systems of their vehicles sold in Massachusetts, as Subaru and Kia had done. AAI has argued that this is merely avoidance of the law, not compliance, and does not accomplish the wishes of the state’s voters.

AAI and Healey sounded similar themes over the definition of “open access,” which AAI takes to include the ability to “send commands to in-vehicle components if needed for purposes of maintenance, diagnostics and repair.”

“[I] the Court determines that the term ‘open access’ does not preclude a manufacturer from imposing authorization (including authentication) restrictions on access to the platform, and that ‘open access’ does not require the ability to write data to the platform, that may reduce the loss of cybersecurity protections that otherwise would occur through compliance with this particular provision/aspect of the Data Access Law,” AAI said. “However, that interpretation of the statute would not eliminate the cybersecurity risks associated with this particular statutory requirement or the Data Access Law in general. Further, no ‘open access’ platform of the type described in the Data Access Law currently exists, and it will take years to develop and implement such a platform.”

“Contrary to Auto Innovators’ argument,” Healey countered, “the trial evidence established that an open access platform can still use security measures to ensure the safety and privacy of the consumer… [and] established that common methods of securing communication, including authentication, Mode 27, and ‘seed and key’ security, can be used with the open access platform described in Section 3.”

AAI filed the suit, AAI v. Maura Healey, in November 2020, after Massachusetts voters approved the Massachusetts Data Access Law. Though the legislation became effective with the 2022 model year, Healey has withheld enforcement of the law as the legal challenge plays out.

More information

Judge gives parties until Oct. 7 answer questions in Mass. ‘right to repair’ case