‘Day of reckoning’: Tracy Law Firm might be coming after more auto body shops

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Legal | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

Though virtually all of his prior work had involved suing OEMs for product defects which allegedly intensify the severity of a collision, Tracy Law Firm attorney Todd Tracy said Wednesday the John Eagle Collision case had opened his eyes to the collision repair industry.

“I am concerned that this is an epidemic,” Tracy said of the allegations in the John Eagle Collision Center litigation.

Body shop director Boyce Willis in a deposition said the facility in 2012 bonded a replacement roof to a 2010 Honda Fit in clear contradiction to the OEM repair procedures. (In fact, Willis insisted he knew it was a better repair than the welds Honda demanded.)

Tracy’s clients Matthew and Martha Seebachan were trapped in the Fit, which caught on fire after a collision with a hydroplaning 2010 Toyota Tundra — and experts argued that the severity of the crash and their injuries were the result of the body shop’s work during the previous owner’s time with the Fit. The T-boned Tundra’s occupants escaped serious harm.

Tracy and the Seebachans are suing the dealership for more than $1 million, accusing it of negligence. A trial is scheduled for September. Tracy said he couldn’t discuss whether settlement talks had occurred. (Editor’s note: All highlighting in hyperlinked documents done by Tracy Law Firm.)

The dealership’s law firm did not respond to a message for comment last week. In an answer to the initial version of the lawsuit, John Eagle Collision said some combination of the Seebachans, another party (presumably the other driver) or the accident itself were responsible for what happened. It also argued that the couple’s pre-existing and subsequent conditions and failure to mitigate their situation could be to blame for the outcome.

‘Sometimes one just grabs you’

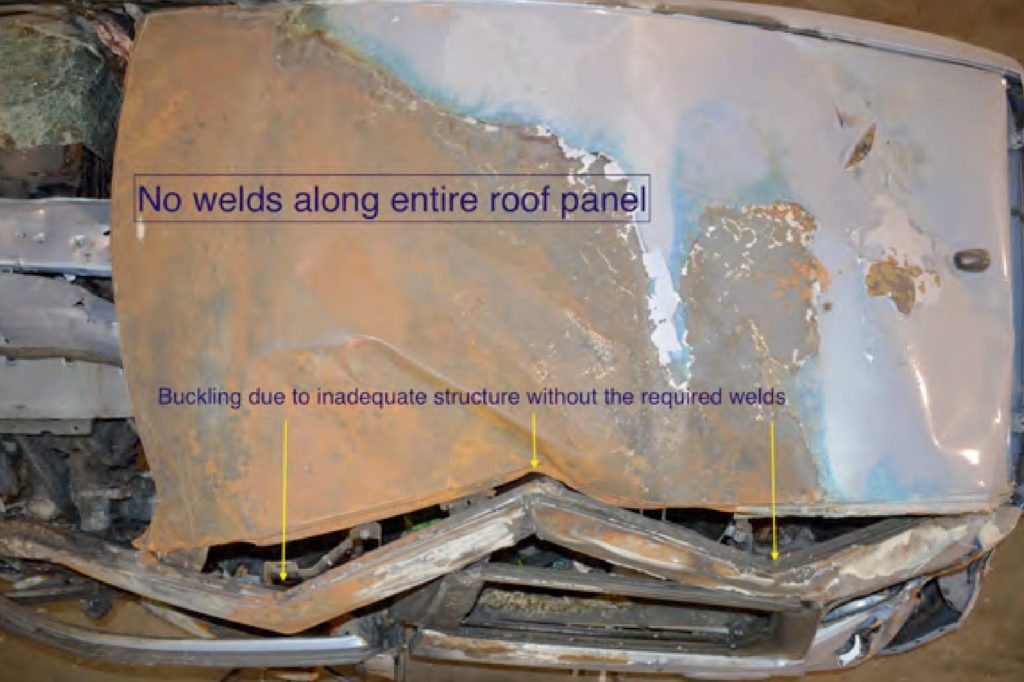

Originally, Tracy looked at the case as a possible lawsuit against Honda, only to realize what the shop had allegedly done. Willis said the shop’s procedure would have been to use an adhesive and four tack welds to replace a roof; Tracy said no tack welds were present at all.

“Sometimes one just grabs you,” he said.

In the past, Tracy said he rejected cases where the damage was too great to indicate whether there was an OEM defect. But now, he said he wondered how many of those cases had a poor collision repair as a contributing factor.

“Nothing is getting past us (in the future),” he said.

The 2010 Honda Fit has been proven by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety to withstand a 40 mph moderate-offset frontal crash well. The road had a speed limit of 75 mph, but a police report doesn’t indicate how fast the Fit was traveling when it struck the Tundra.

However, Tracy said Wednesday that the delta-V — the change in velocity experienced during the impact — was “well under the compliance testing” and in the 28-33 mph delta-V range. That demolishes the argument that even a new car would have suffered such damage in the crash, according to Tracy.

“The 2010 Honda Fit was originally designed to provide structural and fuel system crashworthiness protection, which would prevent serious injuries to occupants in this foreseeable accident,” former Ford GT engineer and plaintiff consultant Neil Hannemann wrote. “In fact, the 2010 Honda Fit receives the highest rating from the IIHS for the moderate offset impact test, which is virtually identical in terms of crash forces to the subject accident.”

Hannemann said that in his opinion, the failure of the roof during the crash compromised the overall structure and collision energy management of the vehicle — contributing to the Seebachans being trapped inside and the subsequent fire. Both of the Fit’s lower frame rails detached, one of them striking the fuel tank located under the driver and passenger, he wrote.

“It can be seen that no welds are present,” Hannemann wrote. “The (Z-)buckling of the cant rail is due to the lack of welding of the roof panel, which was designed to be welded on and acting as a shear panel for sharing crash loads.”

Second owner

The John Eagle Collision case is notable because it involves the vehicle’s second owner — not the customer who received the 2012 hail damage repair work at the heart of the case.

“It’s like privity with the vehicle manufacturer,” Tracy said. An OEM can be held liable for the performance of the safety cage or even something like a seat belt or airbag — they’re supposed to last the entire life of the vehicle, he argued. So a collision repairer should share a similar responsibility after restoring those systems.

“It (the safety system) doesn’t have the ability to know who owns you,” he said.

“The defendants’ may suggest that pre-owned buyers are not entitled to the same degree of safety as the original owner,” Hannemann wrote. “While the vehicle may be used, have mileage and age, creating wear and tear, this should not affect the important safety systems. These systems do not ‘wear out’ like engines, transaxles, suspension, etc. The safety systems should be designed for the ‘life of the vehicle’. The vehicle structure also does not ‘wear out’, it should maintain its integrity and function for the life of the vehicle. Safety is not related to the age of a vehicle.”

“These people had no earthly idea,” Tracy said. “… How many other people have had this same thing?”

Tracy said a shop must follow OEM repair procedures, for who knows better than the manufacturer how to fix the car?

“The repair facility doesn’t know anything, and the insurance company certainly doesn’t

know anything,” Tracy said.

‘Day of reckoning’

In a statement after the interview, Tracy wrote:

Certified repair shops have a moral and legal obligation to meet OEM repair specifications especially when there’s a written manual on how to repair vehicles to restore the vehicle back to a condition that will ensure crashworthiness.

If a certified repair facility fails to comply with these obligations because of incompetence, negligence or its desire to appease an insurance company, then they subject themselves to civil and potentially criminal liability.

The day of reckoning is here—certified body shop facilities better stop listening to the insurance companies they get paid by and start listening to the OEM that spent hundreds of millions of dollars developing, designing, manufacturing and testing vehicles to provide maximum protection in foreseeable accidents.

Insurance companies don’t repair vehicles and don’t develop, design, manufacture and test vehicles. As such, they should stay out of the way of those who are charged with protecting our family should an accident happen.

These same body repair shops should also be cautious of what aftermarket vendors tell them. Adhesives may be great for some applications but unless specifically authorized by the OEM for a specific structural component, the body shop should defer to the OEM. Why—because the OEM developed, designed, tested and manufactured vehicles to be constructed in a certain way to maximize crashworthiness.

The FMVSS regulations were not promulgated to hold aftermarket vendors responsible for complying with the regulations. So, its easy for them to promise the earth, moon and stars when they are selling their glue to a body shop. If I were a body shop, I would ask to see crash testing of specific make, model and year vehicles where the bevy of frontal, side, rear and rollover testing has been done with the vendor’s substitute product was used.

Gluing or bonding panels if the vehicle was originally developed, designed, tested and manufactured is proper with materials such as carbon fibre, magnesium, aluminum. However, when welds are are called for, there’s a reason.

We should note that 3M, who manufactured the adhesive Willis thought had been used, specifically advises shops that Honda says to weld the vehicle instead — a point Tracy seized upon while deposing Willis.

Tracy put particular emphasis on a shop’s OEM certifications, arguing that this compels them to follow OEM repair procedures.

But it seems to us that anyone who ignored the instructions of the company that built the car could be an easy litigation target for an attorney like Tracy — regardless of the shop’s certification status. Either a shop didn’t know of the existence of OEM repair procedures and is incompetent, or it did know and it’s negligent in not following them.

Other aftermarket cases

Tracy described a few instances in which he’d litigated against an aftermarket automotive provider. In one case, he sued a shop which rather than correctly fix a frequently activating airbag light, “they took the airbag fuse out. Which disassembled all the airbags.”

Other instances involve aftermarket modifications that affect the safety of the vehicle.

“I do a lot of lift kit cases,” Tracy said. Airbags might not deploy as intended following such a modification.

He also has sued stereo shops, giving as an example the installation of a massive audio device which becomes a heavy “flying projectile” in a 30 mph delta-V collision.

More information:

Tracy Law Firm via PR Newswire, July 24, 2017

Images:

Though virtually all of his prior work had involved suing OEMs for product defects which intensify the severity of a collision, Tracy Law Firm attorney Todd Tracy said Wednesday the John Eagle Collision case had opened his eyes to the collision repair industry. (Greg Folkins photo; provided by Tracy Law Firm)

Ford GT engineer and plaintiff consultant Neil Hannemann wrote that in his expert opinion, the failure of the roof of the Seebachans’ 2010 Honda Fit during a crash compromised the overall structure and collision energy management of the vehicle — contributing to the Seebachans being trapped inside and a subsequent fire. (Neil Hannemann report; provided by Tracy Law Firm)

These graphics from the Tracy Law Firm compares where the original welds on a Honda Fit would be compared to the alleged absence of welds on the Seebachans’ 2010 Fit. (Provided by Tracy Law Firm)