Analysis: Wash. OIC conducts shaky consumer study to examine auto insurer steering

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Insurance | Legal | Market Trends

The Washington Office of the Insurance Commissioner relied in part on a quantitatively lax study of consumers to conclude that steering was a nonissue in the state, based on an analysis by a statistics minor with ties to a body shop.

Lauren Wolfs, who studied quantitative science at the University of Washington, had pointed out issues with two pieces of OIC research mentioned in its decision last year not to pursue steering rulemaking. She had been commissioned to perform the work by her former employer, Haury’s Lake City Collision.

“The results of our efforts to investigate the issue of consumer steering did not reveal sufficient facts to support a rule-making identifying this an as unfair practice,” OIC policy and rules manager Candice Myrum wrote to state Rep. Steve Kirby, D-Tacoma, in a June 22, 2018, letter recently provided by Haury’s. “As a result, we will not move forward with a rule-making on that topic.”

Kirby had petitioned for regulation of various settlement practices, including steering.

An OIC study of 174 Washington insurance carriers had problems, based on Wolfs’ analysis, but it at least had a large sample size. A second study of consumers only received answers from 32 people — too low to draw conclusions, she wrote.

“In matters of great importance, such as upholding consumer protection, I strongly advocate a rigorous scientific approach to research and problem solving,” Wolfs wrote. “I am sure this is also the intent of the Insurance Commissioner; however, my analysis of the currently available findings concludes that the 2018 study was not designed in such a way that statistically significant results could truly be obtained. In short, based on my knowledge of statistics, I do not believe the current study is sufficient, and for the sake of consumer protection, better science must be utilized to properly investigate the matter of alleged steering.” (Emphasis Wolfs’.)

“The scope of our survey was never intended to be statistically valid sample of Washington consumers, the purpose was to evaluate the data available to our agency,” communications manager Karen Klotz wrote in an email in response to our request for comment on Lauren Wolfs’ criticism of the survey and OIC’s conclusions.

“Based upon the data obtained from the survey, it does not appear a trend has been established to substantiate that insurers are steering consumers,” the OIC’s Andy Swokowski wrote in a report provided to King.

Wolfs, who holds a University of Washington bachelor’s in environmental science and resource management and a minor in quantitative science, said the agency needed good results from insurers and consumers so it could “get the whole story.”

“First, it seems immediately obvious that asking only the insurers – i.e. the group allegedly engaging in an unlawful practice – for their side of the story seems incredibly biased,” Wolfs wrote. “Although one should assume the responses are truthful based on a presumption of innocence, it cannot be overlooked that these organizations will be highly motivated to paint themselves in the best light, and it is unlikely they will admit to any practice that could be considered unlawful steering. To get the whole story, claimants must be surveyed about their experiences as well. Naturally, they will not have the inside information that insurers could provide, but they will be able to share their experience and show a clear picture of how communication was received. Unlike insurers, they will have nothing to lose by recounting incidences of steering.”

Swokowski sent invitations to 185 consumers who had filed complaints to the OIC. Only thirty-two consumers spread across a variety of carriers replied, and not all responded to each one of the three questions.

“Recall that sample size is very important in obtaining rigorous data,” Wolfs wrote.

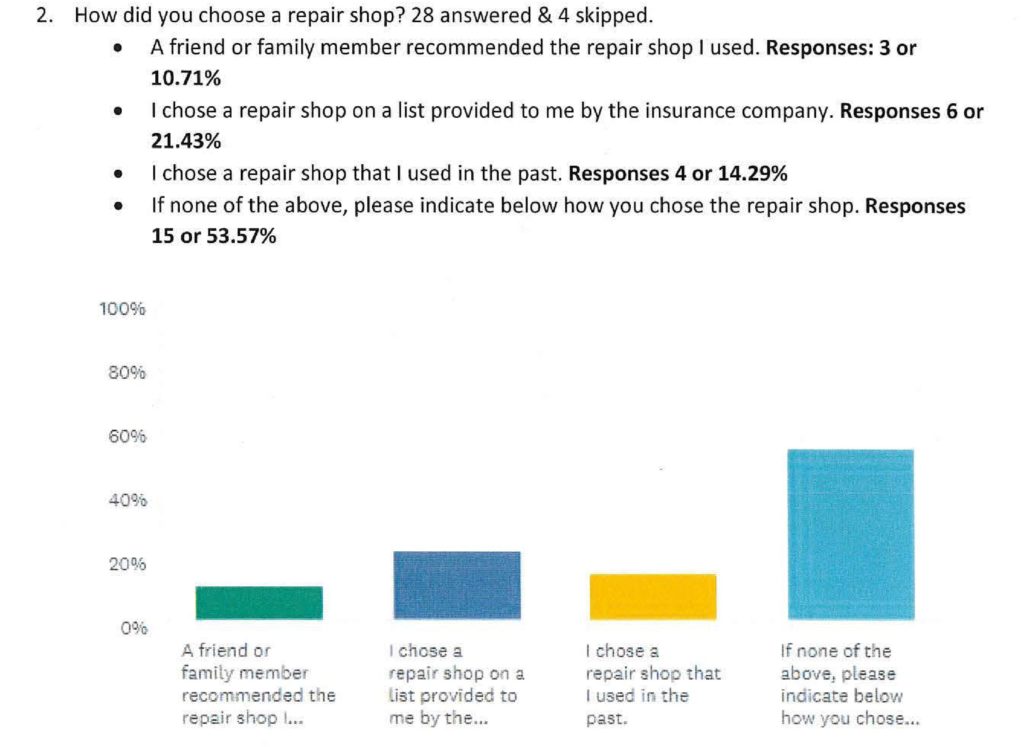

Only 28 of the 32 consumers answered a question asking how they had picked a repair facility.

“The question posed also did not truly ask the question ‘did an insurer influence your decision?’ OR ‘did you choose an insurance network shop or a non-insurance network shop?'” Wolfs wrote. “It does ask the respondents how they chose, but the responses still leave other questions unanswered. The fact that the most common answer was ‘none of the above/other’ makes it difficult to draw any conclusions without more information. Fifteen respondents – over half – chose this answer. Analyzing differences in percentage among three remaining answers with only a total of thirteen respondents is almost meaningless. A much larger sample size is required to reliably analyze the state of the industry.” (Emphasis hers.)

“Furthermore, the ‘Question 2’ as written will not address any incidences of steering that were ultimately unsuccessful. If steering includes attempts by an insurer to persuade a claimant to use a DRP, then only the point-blank question ‘did your insurer attempt to persuade you to use their DRP?’ will uncover these incidents. If a claimant, for whatever reason, had a shop of their own in mind and was unpersuadable in choosing another, their answer of ‘I chose my own shop’ will hide the fact that steering still did occur in their claim. Regardless of a claimant’s ultimate choice, if the goal is to discern whether or not steering is occurring, all instances of attempted persuasion must be included in this analysis.” (Emphasis hers.)

Asked if the consumer was satisfied with their repairs, 30 responded, with 14 saying no.

“Of the 14 consumers that responded ‘no’ for question 3, it appears that three of those consumers chose the shop without influence from the insurer,” Swokowski wrote. “Five did not identify how they chose the repair shop, or no repairs were completed. Six chose the shop with influence from the insurer.

“Of the 10 consumers that had some influence by the insurer, six were not satisfied with the repairs, while three were satisfied with the repairs. There were no repairs completed for one consumer since the vehicle was determined to be a total loss.”

Wolfs wrote that the sample size was too low and a t-test was necessary, though it’s unclear where she derives her associated reference to the OIC assuming 14 shops weren’t influenced by an insurer.

Wolfs pointed out that the study also relied on a statistically questionable data set: Consumers who filed claims.

“To analyze the steering issue statewide, the survey should be given to truly random claimants,” Wolfs wrote. “The use of a subset of claimants who had already filed a complaint makes the results highly at risk for bias It is unknown from the results what any of these claimants had complained about, or what other dissatisfaction – whether with a shop or an insurer – may have influenced their responses. It is unknown whether this complaint-filing subset of people is more or less likely to report steering, and with no way to correct for this unknown factor, none of the results are valid. A large, random sample must be used instead.” (Emphasis hers.)

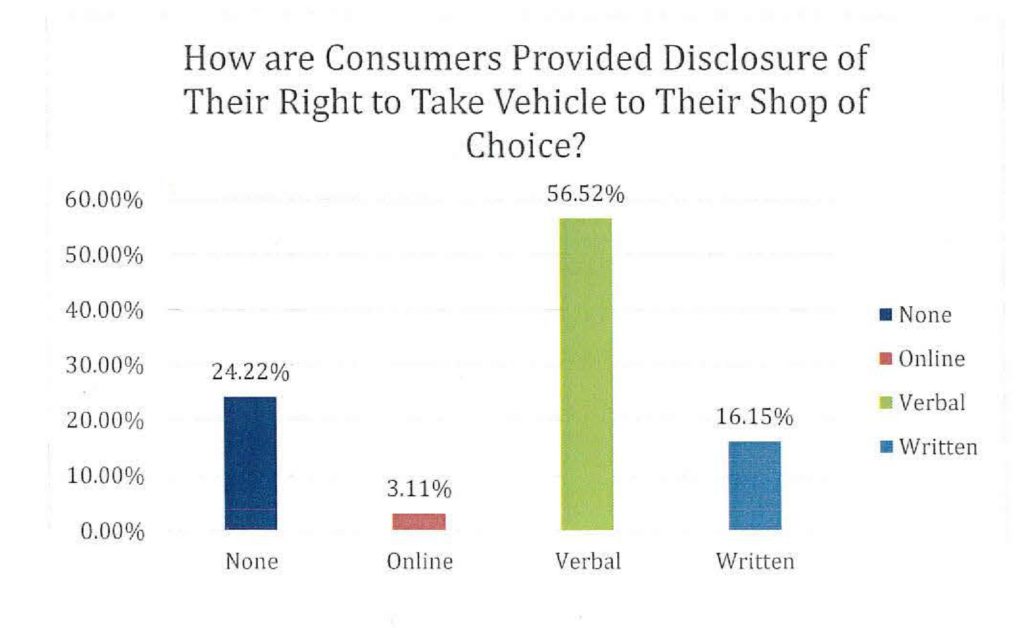

Nearly a quarter — 24.22 percent — of insurers responding to the OIC’s other study of 174 insurers reported not providing consumers with any notice of their right to pick a shop. A little more than 3 percent of carriers notified consumers online. Nearly 57 percent informed customers verbally. Washington has a shop choice law but does not appear to have a requirement insurers tell customers about it.

Wolfs pointed out the flaw in assuming the customers who were notified weren’t steered.

“First, the results of how consumers are informed of their right to choose their own shop is very concerning,” Wolfs wrote. “Over half of insurers give only a verbal notification (nearly impossible to prove) and almost a quarter do not inform consumers at all. In a situation where many consumers have a limited understanding of insurance, not informing them can be considering lying by omission, especially if communication is worded in a way that is misleading. For example, an insurer might say, ‘Well, XYZ shop isn’t in our network,’ and without being informed of their rights, a consumer might assume that they cannot take their vehicle to that shop. Other insurers might say, ‘We have DRP shops at location A and location B, which is more convenient for you?’ and without knowing their rights, a consumer might assume those are their only options.”

Wolfs called for written notification to be enacted into law, calling it the “gold standard.”

“Consistent language should be used,” she wrote. “Verbal or non-existent notifications are impossible to trace and are too vulnerable to being abused or used in a misleading way.”

More information:

“Statistical Analysis and Recommendations for Further Research”

Lauren Wolfs, 2018

Images:

Democratic Washington Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler testifies on a bill. (Provided by Washington Office of the Insurance Commissioner)

A study receiving results from 32 customers who filed a complaint with the Washington Office of the Insurance Commissioner might be lacking in statistical rigor, based on an analysis from a University of Washington statistics minor with ties to a body shop. (Provided by OIC)

The Washington state Office of the Insurance Commissioner had in 2017 polled the state’s 282 known auto insurers recorded in the National Association of Insurance Commissioners database in December 2017 and received responses from 174 of them by Jan. 19, 2018; four more requested exemptions. (Provided by OIC)