DOL clarifies rules on small-biz paid sick leave for COVID-19 illness, childcare

By onAnnouncements | Business Practices | Legal | Repair Operations

Rewritten Department of Labor guidance issued Friday might offer auto body shop employers, employees, and managers greater clarity on the federal COVID-19 paid sick leave rules for small businesses.

The “Families First Coronavirus Response Act,” House Resolution 6201, requires employees with less than 500 employees to temporarily offer paid sick and family leave under certain conditions related to the COVID-19 coronavirus response. It also gives gives employers tax breaks equal to the amounts paid out under this new mandate.

The state of New York sued the Department of Labor over the regulations it developed for the law. The U.S. Southern District of New York on Aug. 3 determined some rules were invalid, including a “FFCRA” paid leave exemption for employees who wouldn’t have had work anyway, and a rule requiring employees to get employee permission for intermittent leave.

On Friday, the DOL explained and rewrote its regulations in light of the ruling. It said the revisions would become effective Wednesday.

“As the economy continues to rebound, more businesses return to full capacity, and schools reopen, the need for clarity regarding the Families First Coronavirus Response Act paid leave provisions may be greater than ever,” DOL Wage and Hour Division Administrator Cheryl Stanton said in a statement. “Today’s updates respond to this evolving situation and address some of the challenges the American workforce faces. Our continuing robust response to this pandemic balances support for workers and employers alike, and remains our priority.”

‘Families First’ recap

According to HR 6201, employers must give “paid sick time to the extent that the employee is unable to work (or telework)” for reasons like:

(1) The employee is subject to a Federal, State, or local quarantine or isolation order related to COVID–19.

(2) The employee has been advised by a health care provider to self-quarantine due to concerns related to COVID–19.

(3) The employee is experiencing symptoms of COVID–19 and seeking a medical diagnosis.

(4) The employee is caring for an individual who is subject to an order as described in subparagraph (1) or has been advised as described in paragraph (2).

(5) The employee is caring for a son or daughter of such employee if the school or place of care of the son or daughter has been closed, or the child care provider of such son or daughter is unavailable, due to COVID–19 precautions.

(6) The employee is experiencing any other substantially similar condition specified by the Secretary of Health and Human Services in consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Secretary of Labor.

Full-time employees are limited to 80 hours. Part-time staffers get as many hours as they would on average work in two weeks.

Employers must cover sick time at the employee’s regular rate or minimum wage, whichever is higher, for Reasons 1-3 above and two-thirds of that amount for Reasons 4-6.

Workers using the sick time for Reasons 1-3 will see the employer requirement max out at $511 a day or $5,110 in the aggregate; reasons 4-6 have an employer ceiling of $200 a day or $2,000 altogether.

Reason 5 — caring for the kid whose day care or school is closed — can be used for up to 12 weeks, “two weeks of paid sick leave followed by up to 10 weeks of paid expanded family & medical leave,” according to the DOL.

Businesses with fewer than 50 workers can request an exemption to the mandate they pay sick leave to employees “caring for a son or daughter of such employee if the school or place of care of the son or daughter has been closed, or the child care provider of such son or daughter is unavailable, due to COVID–19 precautions.” The Department of Labor can grant that exemption “when the imposition of such requirements would jeopardize the viability of the business as a going concern.”

DOL: No paid COVID-19 leave without work

As the DOL described it, the District Court had a problem with the agency’s work availability requirement for two reasons. First, the agency failed to adequately explain its stance, and second, it only explicitly applied the mandate to three of the six reasons.

The agency on Friday clarified it meant six out of six and rewrote the regulation to say that. It also discussed other elements of its thought process.

The DOL’s position remains that your boss doesn’t have to pay you FFCRA leave if the business wouldn’t have had work for you anyway. The absence of work remains a plausible scenario in collision repair; a recent CCC analysis found U.S. repairable appraisals remain down in August — and might have been worse if the weather weren’t bad in multiple parts of the country.

“The Department’s continued application of the work-availability requirement is further supported by the fact that the use of the term ‘leave’ in the FFCRA is best understood to require that an employee is absent from work at a time when he or she would otherwise have been working,” the DOL wrote. “As to this point, the District Court concluded that the statute did not mandate such an interpretation. After reconsideration, the Department now reaffirms that even if ‘leave’ could encompass time an employee would not have worked regardless of the relevant qualifying reason, the Department, based in significant part on its experience administering and enforcing other mandatory leave requirements, interprets the FFCRA as allowing employees to take paid leave only if they would have worked if not for the qualifying reason for leave. ‘Leave’ is most simply and clearly understood as an authorized absence from work; if an employee is not expected or required to work, he or she is not taking leave.”

The DOL said this was consistent with how it has handled the idea of leave under the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act.

“The Department notes that removing the work-availability requirement would not serve one of the FFCRA’s purposes: discouraging employees who may be infected with COVID-19 from going to work,” the agency wrote. “If there is no work to perform, there would be no need to discourage potentially infected employees from coming to work through the provision of paid FFCRA leave. Nor is there a need to protect a potentially infected employee who stays home from an employer’s disciplinary actions if the employer has no work for the employee to perform.

“Removing the work-availability requirement would also lead to perverse results. Typically, if an employer closes its business and furloughs its workers, none of those employees would receive paychecks during the closure or furlough period because there is no paid work to perform. But if an employee with a qualifying reason could take FFCRA leave even when there is no work, he or she could take FFCRA leave, potentially for many weeks, even when the employer closes its business and furloughs its workers. The employee on FFCRA leave would continue to be paid during this period, while his or her co-workers who do not have a qualifying reason for taking FFCRA leave would not. The Department does not believe Congress intended such an illogical result.”

Employers shouldn’t get cute with this concept to avoid paying FFCRA leave, however.

“To be clear, the Department’s interpretation does not permit an employer to avoid granting FFCRA leave by purporting to lack work for an employee,” the DOL wrote. “The work-availability

requirement for FFCRA leave should be understood in the context of the applicable antiretaliation provisions, which prohibit employers from discharging, disciplining, or discriminating

against employees for taking such leave. Accordingly, employers may not make work unavailable in an effort to deny FFCRA leave because altering an employee’s schedule in an adverse manner because that employee requests or takes FFCRA leave may be impermissible retaliation.”

The DOL also explained that it wouldn’t permit what New York feared would be “a capacious and unpredictable loophole basing eligibility on the hour-by-hour or day-by-day happenstance that work may not be available.”

The DOL said the rule “does not operate as an hour-by-hour assessment as to whether the employee would have a task to perform but rather questions whether the employee would have reported to work at all. Moreover, the availability or unavailability of work must be based on legitimate, non-discriminatory and non-retaliatory business reasons.” (Emphasis ours.)

Intermittent leave

It’s possible for an employee to space out their paid time off rather than be locked into a single block. However, this is only permitted if the employee needs to watch a kid whose school or daycare has been closed or if the employee is teleworking. The DOL pointed out — and the court agreed — that intermittent leave under other FFCRA scenarios would just spread COVID-19 around. (Think about it: If someone is a confirmed or potential coronavirus vector, you don’t want them popping in and out of the office.)

The DOL said a teleworking employee must get employer approval for an intermittent FFCRA leave schedule, arguing that they would have already discussed teleworking with their employer in the first place anyway. However, they don’t need to obtain “certification of medical need,” the DOL said Friday.

“The Department has thus aligned the employer-agreement requirements to apply to both telework and intermittent leave from telework,” the agency wrote. “The Department believes that its approach affords both employers and employees flexibility. In many circumstances, these agreed-upon telework and scheduling arrangements may reduce or even eliminate an employee’s need for FFCRA leave by reorganizing work time to accommodate the employee’s needs related to COVID-19.”

The DOL won’t require employer permission for many situations where an employee must take care of a healthy child whose school or daycare has been disrupted by COVID-19. If a

“The employer-approval condition would not apply to employees who take FFCRA leave in full-day increments to care for their children whose schools are operating on an alternate day (or other hybrid-attendance) basis because such leave would not be intermittent under § 826.50,” the DOL wrote. “In an alternate day or other hybrid-attendance schedule implemented due to COVID-19, the school is physically closed with respect to certain students on particular days as determined and directed by the school, not the employee. The employee might be required to take FFCRA leave on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of one week and Tuesday and Thursday of the next, provided that leave is needed to actually care for the child during that time and no other suitable person is available to do so. For the purposes of the FFCRA, each day of school closure constitutes a separate reason for FFCRA leave that ends when the school opens the next day. The employee may take leave due to a school closure until that qualifying reason ends (i.e., the school opened the next day), and then take leave again when a new qualifying reason arises (i.e., school closes again the day after that). Under the FFCRA, intermittent leave is not needed because the school literally closes (as that term is used in the FFCRA and 29 CFR 826.20) and opens repeatedly. The same reasoning applies to longer and shorter alternating schedules, such as where the employee’s child attends in-person classes for half of each school day or where the employee’s child attends in-person classes every other week and the employee takes FFCRA leave to care for the child during the half-days or weeks in which the child does not attend classes in person. This is distinguished from the scenario where the school is closed for some period, and the employee wishes to take leave only for certain portions of that period for reasons other than the school’s in-person instruction schedule. Under these circumstances, the employee’s FFCRA leave is intermittent and would require his or her employer’s agreement.”

Giving notice

Finally, the DOL retooled its rules on giving the boss notice of leave. The DOL had demanded documentation “prior to” taking FFCRA leave — a requirement the Southern District of New York pointed out violated the law.

Instead, the DOL refined the regulations to reflect the nuances of the law.

The DOL said employees instead could offer notice “as soon as practicable, which in most cases will be when the employee provides notice under § 826.90.” But the law does require notice in advance for some scenarios, based on the DOL’s reading of the statute.

The agency offered an example to illustrate its future direction: “For example, if an employee learns on Monday morning before work that his or her child’s school will close on Tuesday due to COVID-19 related reasons, the employee must notify his or her employer as soon as practicable (likely on Monday at work). If the need for expanded family and medical leave was not foreseeable—for instance, if that employee learns of the school’s closure on Tuesday after reporting for work—the employee may begin to take leave without giving prior notice but must still give notice as soon as practicable.”

More information:

“Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Employee Paid Leave Rights”

Department of Labor, 2020

Department of Labor, Sept. 11, 2020

Temporary DOL rule on FFCRA (Expected to become official on Sept. 16, 2020)

Department of Labor, Sept. 11, 2020

Images:

The U.S. Department of Labor headquarters is shown. (JL Images/iStock)

Republican President Donald Trump, center, signs House Resolution 6201 on Wednesday. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is at left; Republican Vice President Mike Pence is at right. (Shealah Craighead/Official White House photo)

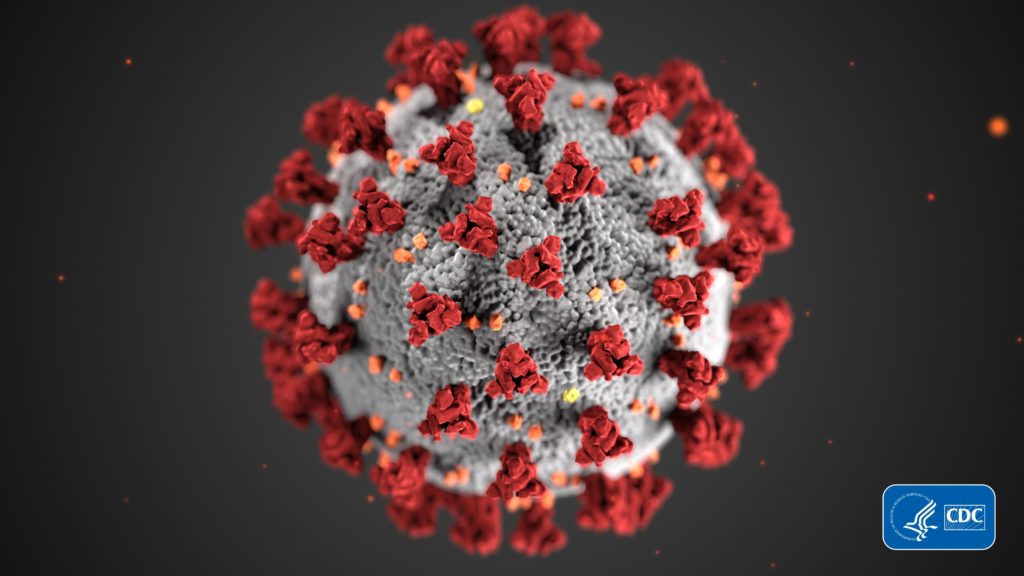

This Centers for Disease Control and Prevention image depicts a coronavirus. The novel coronavirus “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2) is linked to a respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China. The medical condition has been named “coronavirus disease 2019” (COVID-19). (Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins/CDC)