Attorney: Judge rejected notion Meineke lacks responsibility for franchisee service

By onBusiness Practices | Legal | Market Trends | Repair Operations

A $12.5 million settlement recently agreed to by Meineke and a franchise shop came about a year after the national brand was unable to exit the case on grounds it lacked responsibility for the independent location’s actions.

“They tried to get out of the case,” plaintiff’s attorney Lawrence Kahn of the Lawrence Kahn Law Group said Monday. “… The judge wasn’t buying it,”

King County Superior Court Judge Catherine Shaffer’s June 16, 2020, order refusing Meineke’s request for summary judgment raises questions about the exposure of collision industry network organizers should similar litigation arise.

Kahn sued Meineke and its Everett, Wash., franchise Meineke No. 4333, alleging the shop failed to warn plaintiff Janyce MacKenzie about dangerously worn tires during two 2016 service visits ostensibly featuring tire inspections. The left rear tire of MacKenzie’s 1998 Ford Explorer delaminated on a 70 mph stretch of Interstate 90 in Montana, resulting in a crash that left her with severe injuries. (For convenience’s sake, we’ll refer to the corporate Meineke here as “Meineke” and the individual Meineke shop as “Meineke 4333.”)

Neither Meineke nor Meineke 4333 admitted any liability under the terms of the settlement. Both entities have denied all of the lawsuit’s negligence allegations.

Tire quality

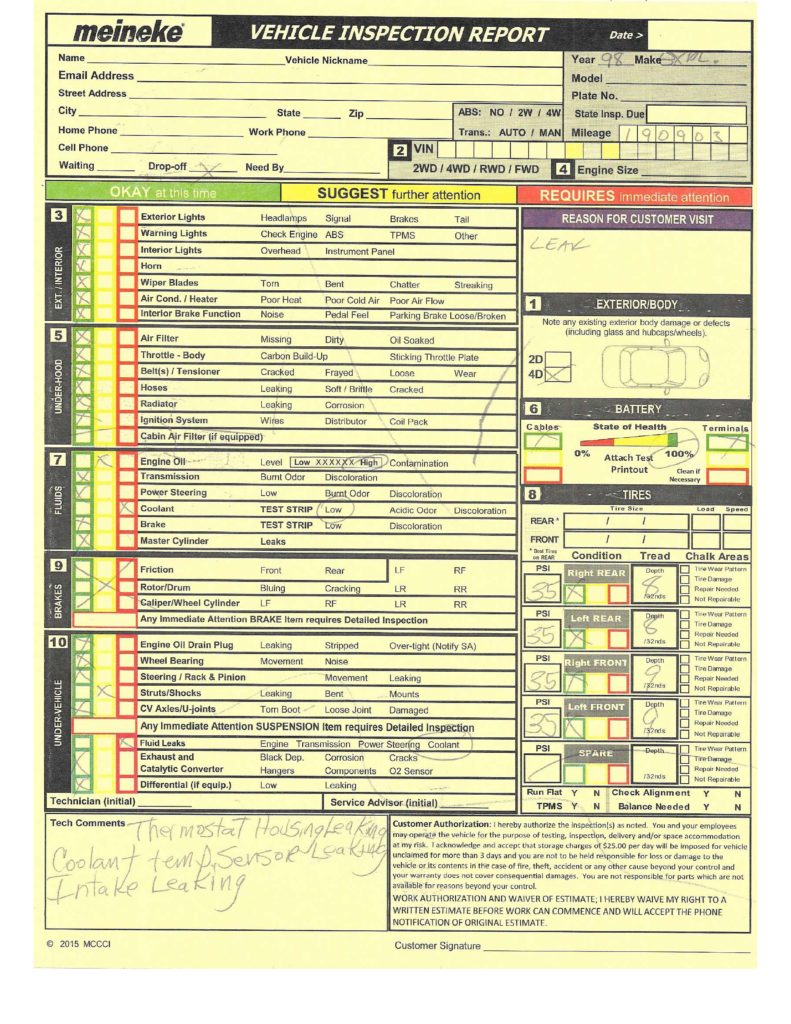

Plaintiff’s expert Thomas Vadnais said Meineke 4333’s April 22, 2016, inspection report listed the front tires at 8/32 inches of tread and the rear ones as 9/32 inches, despite a January 2016 Sears inspection recording them at 2/32. (Sears, which denied negligence, was originally named as a defendant but dropped after its bankruptcy partway through the litigation.)

Vadnais argued that if Meineke 4333’s measurements had been accurate, the tread would have had to experience “an unrealistically fast wear rate” between the April inspection and the Aug. 4, 2016, crash.

“While the tread depths of the tires I measured after the rollover ranged from 1/32 to 4.5/32 inch, most tread grooves measured 3/32 to 4/32 inch remaining tread depths,” Vadnais wrote. However, Meineke 4333 said Montana Highway Patrol measurements put the tire treads at between 4/32 and 7/32.

According to MacKenzie’s lawsuit, the Washington Meineke also had an opportunity to alert her to the tire condition on Aug. 2, 2016 — two days before the crash. She had brought the Explorer to the shop to “make sure it was safe” ahead of a move from Washington state to Iowa, according to a court filing.

“No Vehicle Inspection Report for this visit could be produced by Meineke,” Kahn wrote in a response to an unsuccessful Meineke corporate motion for summary judgment. “Yet, Plaintiff was told that her tires would be checked as part of the service.”

“They told her her tires were fine,” Kahn said Monday.

Counsel for Meineke 4333 pointed to potential flaws in the plaintiff’s case when contacted Monday.

“Other experts said the defect in the tire that blew could not have been detected by the ‘oil and lube’ trained technicians,” Meineke 4333 attorney Nancy McKinley of Fallon McKinley wrote in an email.

“The problem for the defense in this case was the fact that plaintiff more than likely was not wearing her seatbelt, was ejected from the car through the sun roof. That is one of the reasons she was so severely injured. However, under Washington Law, the fact that someone is not wearing a seatbelt is not evidence that can be used against them in Court.”

Franchisor sued

MacKenzie also sued the national Meineke brand for negligence, even though as a franchisor it doesn’t technically own or operate Meineke 4333. Her lawsuit accused Meineke corporate of causing the injuries:

a. In that it failed to ensure that its franchisee possessed the requisite qualifications to competently operate a Meineke franchise which offered tire inspection and maintenance services.

b. In that it failed to ensure that its franchisee hired mechanics with the requisite qualifications to competently operate a Meineke franchise which offered tire inspection and maintenance services.

c. In that it failed to monitor its Meineke franchise at a time of transition from primarily muffler services to a time of offering a broader spectrum of services including tire services and to ensure that the franchise was competently equipped and had personnel qualified to the tasks; and/or

d. In that it failed to conduct adequate inspection of its franchisee to ensure that its employees were competent to offer tire services.

e. In that it failed to ensure that its franchisee actually performed its advertised complete and competent tire inspections on all customer vehicles, including but not limited to the Subject Vehicle, even though it had actual knowledge that its franchisee was not performing complete and competent tire inspections on all customer vehicles. (Minor formatting edits.)

Neither Meineke corporate nor its attorneys responded to a request for further comment.

Some of these arguments seem like accusations a defendant could attempt against companies which organize and oversee networks of independent collision repairers, be this under a franchise, OEM certification or insurer direct repair program arrangement. None of these entities actually own or operate the body shops in these relationships. But they do hold locations to specific standards and promote those facilities to consumers.

Whether or not the plaintiff would actually be able to keep such a case from being thrown out of court is a different question. But Meineke’s argument, MacKenzie’s response and the judge’s ultimate decision to keep Meineke as a defendant suggest the collision industry might need to look about the exposure an OEM, franchise or DRP network creates on its organizer. A court might not see the relationship as arms-length as one might expect, at least in Washington state.

Kahn said legal precedent dictates that if a franchisor establishes “they want them to do it their way” and outlines how something must be done, “they may be responsible” for the franchisee’s failing.

“They had the authority to intervene and do something,” Kahn said of Meineke. “They didn’t do it. That was their negligence.”

Meineke cited as precedent Folsom v. Burger King, which found the Supreme Court of Washington agreeing that the franchisor restaurant could not be held responsible for security at an independent franchisee location where employees were slain.

That case drew a distinction between items over which Burger King retained control under the franchise agreement and items it didn’t, according to Kahn.

“Folsom is far from the blanket prohibition against imposing liability on a franchisor for the acts and omissions of a franchisee as Meineke suggests,” Kahn wrote.

“… The court in Burger King specifically stated that ‘Burger King’s authority over the franchise was limited to enforcing and maintaining the uniformity of the Burger King system.'”

Kahn mentioned another Burger King case, Bartholomew v. Burger King Corp., The U.S. District of Hawaii found Burger King’s standards for making a burger could signify enough control that a lawsuit alleging metal found in a Triple Whopper could survive a motion for summary judgment.

Franchisors “have to take responsibility to follow through and make sure their franchisees are doing it the right way,” Kahn said.

Meineke: ‘Independent contractors’

“Meineke had no direct duty, whatsoever, to these Plaintiffs, and it is neither vicariously liable for 4333 ’s vehicle/tire inspection, nor is it an agent of 4333,” Meineke’s Jan. 3, 2020, motion for summary judgment stated. “Since the filing of this action, a significant amount of discovery has occurred. The documents and uncontroverted deposition testimony demonstrate that (1) Meineke has absolutely no authority, control, or right to control 4333’s operations, including the conducting of courtesy vehicle inspections and vehicle services recommended or provided to Plaintiff MacKenzie prior to the collision; and (2) Meineke and 4333’s relationship is solely and exclusively contractual pursuant to the Franchise Agreement, which expressly states that 4333 is an independent contractor and not an agent of Meineke. As such, this matter is wholly ripe for summary judgment in Meineke’s favor.”

Meineke’s franchise agreement also states: “You and we are independent contractors. … Nothing contained in this Agreement, or arising from the conduct of the parties hereunder, is intended to make either party a general or special agent, joint venturer, partner or employee of the other.”

Meineke said it gives shops “a system of standards and procedures that, pursuant to the Franchise Agreement, the franchisees are required to follow.” According to the company, a “‘playbook'” within this system helps individual shops follow “The Meineke Way,” which includes an inspection model, but “Meineke does not control or place any requirements on the actual performance of inspection services that the franchisees offer.” (Emphasis Meineke’s.)

Kahn noted in his response opposing summary judgment that the Meineke “System” is defined in the franchise contract as including “service standards.”

The company agreed that franchisees are required to “follow its contractual system,” but only Meineke 4333 could compel local personnel to do anything.

“Meineke’s ‘inspection’ of 4333—and other franchisee locations—is focused on and limited to maintaining brand standards—ensuring that franchisees display correct signage, ensuring that buildings are clean and have a well-maintained appearance, that technicians are in uniform, and that people answer the phone and interact with the customers properly, which includes observing whether the franchise is conducting inspections in order to provide the best customer service under Meineke’ s brand—i.e. ‘enhancing customer goodwill toward the Marks.'”

Brett Harrison, the franchise business consultant assigned to Meineke 4333, was a Meineke employee but only visited the shop at most four times a year for only 2-3 hours at a time, Meineke said. This time was mostly spent focused on retail sales and phone training, according to Meineke.

The consultant “had no ability to force them to comply in any way. Similarly, if a store manager, service manager/writer, or technician did not follow the suggested phone script templates provided by Harrison, did not adopt his suggestions on the use of the vehicle inspection report, or failed to perform an inspection, he had no power or authority to require any of 4333’s employees or personnel to comply and had no disciplinary authority against those employees, 4333, or the MCCC Group,” Meineke wrote. It also observed that its own designee said the franchisor was “’not able to force our franchisees to do something specifically.'” (Emphasis Meineke.)

But Kahn said Meineke could “take legal action against the franchisee in violation of the franchise agreement” if Harrison found a Meineke violating company policies.

Plaintiff: Meineke sets standards

Meineke said doesn’t train employees, though it provides resources for doing so. However, Kahn’s response pointed out that Meineke’s website said “[o]ur certified technicians will inspect your tires, perform a tire repair or replace them entirely,” and the company’s phone training involved service advisers “told to tell customers that certified technicians would inspect their vehicles.”

Meineke said it didn’t require the inspections to be conducted in a certain way, but Kahn said the company did create the form on which they were to document their findings.

Meineke also said it doesn’t control a franchisee’s record keeping, and its consultant has no power to take action against the shop for missing documentation like an inspection report.

“Brett Harrison, the Franchise Business Consultant (‘FBC’) employed by Meineke, conducted an invoice audit of the Franchisee,” Kahn wrote. “He found many invoices lacked Vehicle Inspection Reports and no additional notes written relating to the service. Because there was no Vehicle Inspection Report attached to these invoices, Corporate FBC Harrison assumed that a mandatory inspection was not done.”

Kahn’s response argued that no signs conveyed to the public that the shop was independently owned rather than a franchise. Meineke said the location was required to make this clear, and any failure regarding this disclosure was the fault of the location.

“Plaintiff justifiably believed that the quality of the service paid for was backed by the national Meineke brand,” Kahn wrote. “Would any reasonable person see, among a sea of yellow posters, signs, forms, and advertisements, the fine print saying: ‘This Meineke is independently owned and operated’? If reasonable minds may differ, it is a jury question.”

“I had no idea it was a franchise or independent or independent of the Meineke corporation nor could I,” MacKenzie wrote in an declaration filed with Kahn’s response. “There was no sign saying it was a franchise or independent that I saw on the separate occasions I was there.

“I trusted that the employees at the … location would provide high quality automotive care services because I reasonably figured they were actually part of the Meineke chain, were properly trained by the Meineke national chain, and that Meineke naturally stood behind their work.”

Kahn’s response noted Meineke’s warranty, which applied nationwide. “If a customer came into the Franchisee but had service done at a different Meineke shop, the Franchisee would still honor that other shop’s warranty,” he wrote.

“Plaintiff relies solely upon her belief and general impression from 4333’s marketing and advertising to establish that there was apparent agency,” Meineke replied. “Even if Plaintiff and her husband saw Meineke advertising and recognized the brand name, this is insufficient to establish apparent agency.”

“Plaintiff relies solely upon her belief and general impression from 4333’s marketing and advertising to establish that there was apparent agency,” Meineke replied. “Even if Plaintiff and her husband saw Meineke advertising and recognized the brand name, this is insufficient to establish apparent agency.”

Kahn also challenged Meineke’s assertion it had no control over shops.

“If FBC Harrison found any drastic violation of Meineke’s policies and procedures, he would inform the owner of the business and his superiors at Meineke,” Kahn wrote. “Meineke could then take legal action against the franchisee in violation of the franchise agreement.”

Kahn said Harrison didn’t brought the topic of missing inspections to superiors because he viewed it as his responsibility to correct the franchise.

“Meineke misstates its role by claiming that it does not control or place any requirements on the actual performance of the services that the franchisees offer,” Kahn wrote. “The Franchisee was bound by its Franchise Agreement to adhere to ‘The Meineke Way,’ which specified a system, procedure, and manner of conducting business. It was expressly FBC Harrison’s role to visit and audit franchises to make certain that they were fully complying with the franchise agreement. This included following their ‘300% rule’, and thus, the Franchisee was required by Meineke to actually perform inspection services on 100% of vehicles. If the Franchisee did not comply with this rule, FBC Harrison had a duty inform his Meineke superiors of the breach, who had the power to initiate action against the Franchisee.”

The “300% rule” also included the standard that “100 percent of those inspections were presented to the customer,” as Harrison put it.

Images:

A Washington state woman settled a lawsuit with Meineke and Everett, Wash., Meineke Shop No. 4333 alleging negligence in failing to warn her of the condition of this tire, which delaminated while traveling 70 mph in Montana. (Provided by Lawrence Kahn Law Group)

Though a Sears in January 2016 evaluated plaintiff Janyce MacKenzie’s tires as carrying 2/32 tread depths, Meineke in April 2016 reported them to be either 8/32 or 9/32. (Provided by Lawrence Kahn Law Group)

A Washington state woman settled a lawsuit with Meineke and Everett, Wash., Meineke Shop No. 4333 alleging negligence in failing to warn her of the condition of her 1998 Ford Explorer’s left rear tire, which delaminated while traveling 70 mph in Montana. (Provided by Lawrence Kahn Law Group)

Janyce MacKenzie was driving a 1998 Ford Explorer at 70 mph in Montana when her rear tire delaminated. (Provided by Lawrence Kahn Law Group)