I-CAR offers guidance on EV safety in CIC presentation

By onAnnouncements | Collision Repair | Repair Operations

When a damaged electric vehicle (EV) arrives at a body shop, a prudent first step is to conduct a pre-repair scan of the vehicle where it sits, before moving it into the shop, two presenters from I-CAR told an audience at the Collision Industry Conference last week.

During a special presentation on EV safety procedures, Dirk Fuchs, Director, Technical Programs & Services at I-CAR, noted that when an EV is in a collision, its high-voltage battery pack can suffer damage from the impact, even if there’s no apparent physical damage. If that internal damage has caused a voltage deviation across two or more cells, that will create resistance, and that resistance will create heat that can lead to a fire, Fuchs said.

Scanning, he said, will show the temperatures of each of the hundreds of individual battery cells that make up the pack, flagging a potential problem.

Once the vehicle is in the shop, the next step in the repair procedure, Fuchs said, is to safely disconnect the service connections to the high-voltage pack. “There is a lot of potential of voltage that could hurt us, could hurt the shop and our environment, so we want to safely disconnect to make sure that we can touch the vehicle and its components,” he said.

I-CAR has developed a best practice disconnecting procedure, which can be found on its website at https://rts.i-car.com/best-practices.html. The procedure, Fuchs emphasized, is meant to be used in conjunction with OEM procedures.

Once the connectors are undone, the technician must verify that there is zero electrical potential across the terminals. Niel Speetjens, Senior Manager ADAS/EV Lab Research & Specialty Training for I-CAR, noted that a typical EV battery pack has a potential of 400 to 800 volts, “to propel the vehicle, but also to hurt me, or to burn down the shop. So we want to verify this to zero potential, so it’s harmless to us and our environment.”

Fuchs noted that, although OEM procedures commonly call for the use of a multimeter to check potential, he recommends a simple voltage tool. “With a tool like this, you can’t make a mistake. And it doesn’t need a battery to operate. It takes the power from the measuring source. It doesn’t have to be changed to AC or DC. You measure, and that’s all that you do. It eliminates mistakes, and you don’t want to make a mistake,” he said.

“When it comes to verifying zero potential, this is a task that is crucial, important and lifesaving. We have to make sure the vehicle is really zero potential before I start touching it,” he said.

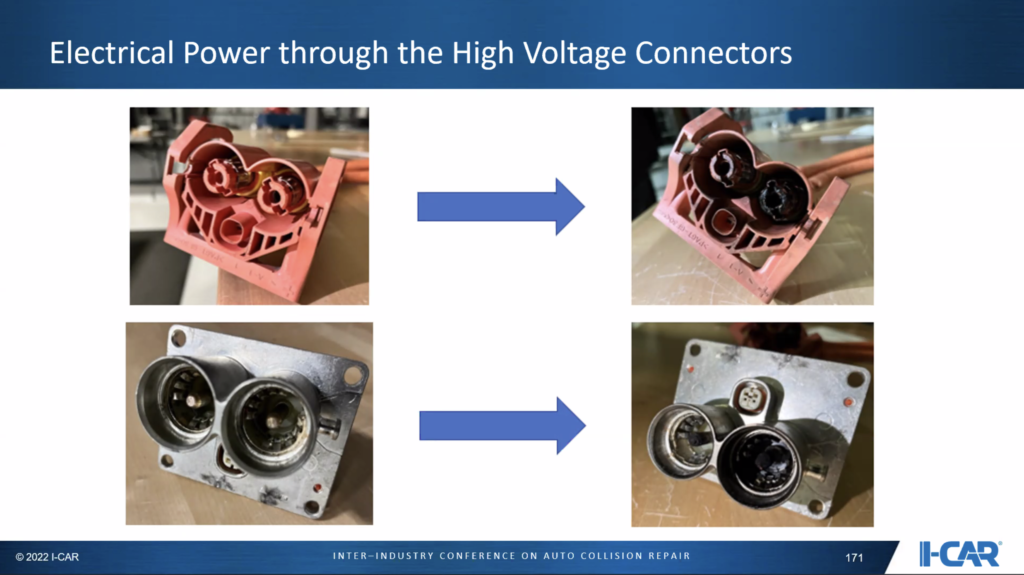

While the vehicle is being repaired, and before the battery pack is reconnected, cleanliness is critical, the two presenters said.

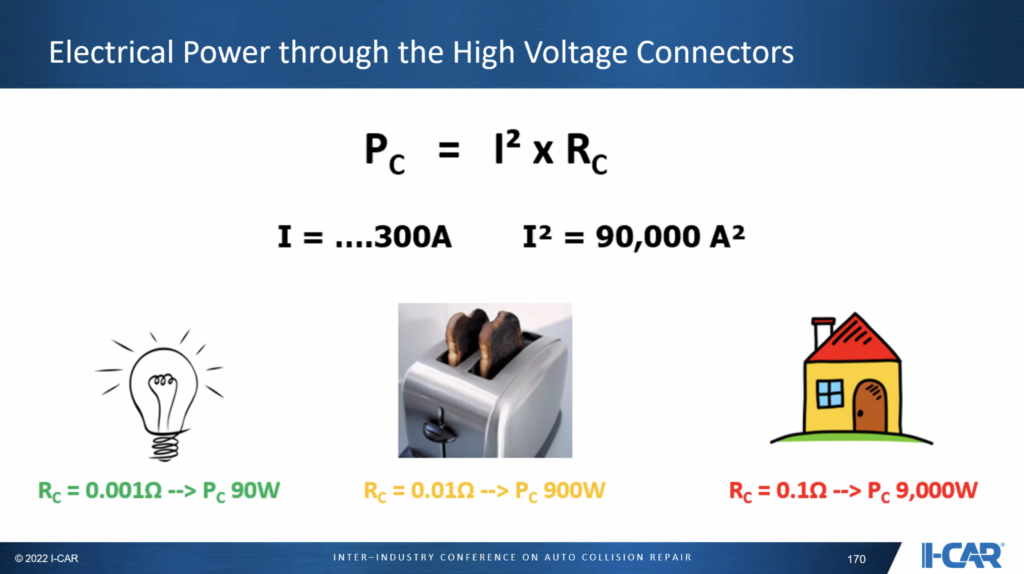

With the amount of electricity flowing through the connectors, even the smallest amount of resistance can produce a large amount of power. Fuchs provided an example, using an EV that might draw 300 amps as it passes another vehicle on a hill.

He said that, with 300 amps, one milliohm of resistance produces 90 watts, enough to light a light bulb; at 10 milliohms, it produces 900 watts, or enough to burn your toast. One hundred milliohms produces 9,000 watts, enough to power an entire house — all passing through that one connector under the car.

Fuchs explained how that resistance can make its way into the connector in the form of contamination while a vehicle is being repaired. Even a tiny amount, invisible to the naked eye, is enough to create a potential hazard, he said.

“What is happening in a repair shop? The system is disconnected. Cables [are] hanging down. Cars getting moved around. Cars get worked on. Vehicles get painted. So what’s happening when a vehicle is getting painted, and all our connectors are open?

“Multiple factors can happen,” he continued. “I bring the car in the spray booth, and the connector hangs down, and my technician sprays and … makes a beautiful job. But that dust, stuff that is floating around, goes into a connector, and resistance changes from 1 milliohm to 10 milliohms, and is not even visible to our [naked] eyes.”

“That’s the reason working clean, covering connectors is the most important thing now in our industry when it comes to electric vehicles,” Fuchs said. “We have to create a clean environment.”

More information

I-CAR offers best practice guide for disconnecting high-voltage EV batteries

Images

Featured image: A technician demonstrates the proper procedure for disconnecting a high-voltage connector on a vehicle. (Screen capture from I-CAR)

Connectors on the right show the effects of overheating from having become contaminated with dirt or dust. (Provided by I-CAR)

From left, I-CAR’s Bud Center, Niel Speetjens and Dirk Fuchs give a special presentation on the safe repair of EVs at the CIC winter 2022 program in Scottsdale, Ariz. (Provided by CIC)

A chart shows the power produced when 400 amps passes through resistance of 1 milliohm, 10 milliohms and 100 milliohms. (Provided by I-CAR).