Consumer group criticizes auto insurers over ‘massive’ salaries paid to top executives

By onInsurance | Legal

The nation’s largest auto insurers are paying their top executives “massive salaries and bonuses,” even as they continue to seek higher premium payments from consumers, according to a review by the Consumer Federation of America (CFA).

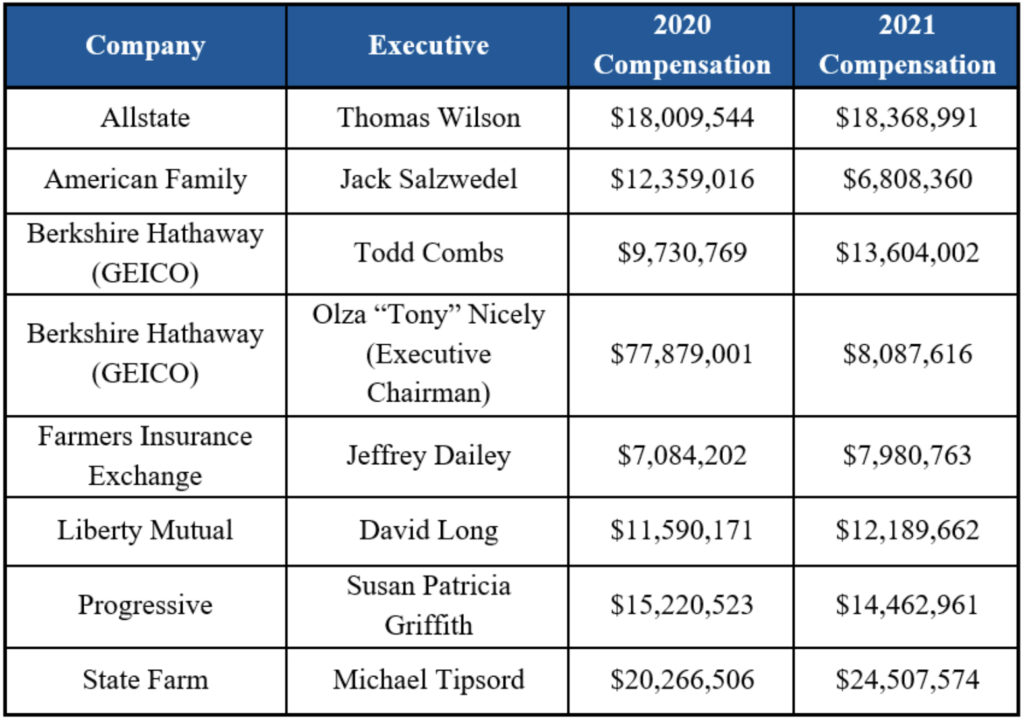

In its review of filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Nebraska Department of Insurance, CFA found that the four largest insurers paid their top executives $196.8 million between 2020 and 2021 – an average annual paycheck of about $25 million.

“While Americans struggle to pay higher insurance premiums and deal with two years of pandemic challenges, insurance executives have taken corporate excess to a new level,” Douglas Heller, Director of Insurance for CFA, said in a statement. “At the same time, they are demanding rate hikes from consumers who are required by law to purchase the product they sell.”

Leading the pack was former GEICO CEO Olza “Tony” Nicely, who received a $77 million “golden parachute,” a large sum exit package, in 2020. Nicely also served as GEICO’s executive chairman during the period, CFA said.

The federation, which in August 2020 accused GEICO of having the nation’s worst COVID refund program in the nation, said the carrier “should return much more premium to drivers, as driving levels remained low.” It also called on GEICO to “end its practice of requiring customers to renew policies before they received their pandemic refund.”

The Alliance said that the $2.1 billion in quarterly earnings brought in by GEICO and its subsidiaries in the second quarter of 2020 showed that the carrier’s pandemic “giveback” program did not fully account for the dramatic reduction in risk it experienced.

CFA also called out the $40.5 million in bonuses paid to State Farm CEO Michael Tipsord since the start of the pandemic. The carrier paid its chief executive cash bonuses of $18.1 million in 2020 and $22.4 million in 2021, against a salary of $1.94 million to $2.15 million.

Record-setting haul

According to Crain’s Chicago Business, Tipsord’s 2021 bonus represents “a record-setting compensation level for the insurer and likely the largest cash haul of any chief executive in the U.S.”

Crain’s pointed out that State Farm, the nation’s largest auto insurer, is not publicly traded, but is technically owned by its policyholders. That means that there are no stock options or shares to give top executives as part of their compensation.

“In past years … State Farm paid its CEO cash totals that generally mirrored the cash received by CEOs of similarly sized publicly traded companies. Something seems to have changed in terms of the insurer’s comp program, but the statement [provided by State Farm] didn’t address that question posed by Crain’s,” the publication said.

Crain’s said Tipsord’s job “is arguably simpler than his peers who run publicly traded companies. He doesn’t have to deal with quarterly reporting, shareholder calls, decisions on regular dividend payments and the general need to keep a stock price rising. State Farm’s capital base is enormous, so it can afford to lose money for even years at a time in order to gain market share if it chooses.”

To put Tipsord’s pay into perspective, Crain’s noted that the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, Jamie Dimon, received $6.5 million in cash, with the rest of his $77.5 million in stock and options.

Other State Farm executives also received big paydays in 2021, Crain’s said. Chief Operating Officer Paul Smith got $8.6 million, up from $6.8 million in 2020 and $3.5 million in 2019, according to the company’s filing. Randall Harbert, chief agency sales and marketing officer, was paid $8.2 million, up from $6.8 million and $3.5 million in 2020 and 2019, respectively.

Allstate’s CEO, Thomas Wilson, who was paid a total of $36.4 million in 2020 and 2021, told shareholders in February that the carrier would be pursuing an aggressive course on rate increases, and said he expected no difficulty with approvals.

Rate increases are “less a political issue than it is a reality issue of looking at the numbers and what is the justifiable and supportable rate increase,” Wilson said. “We’ll have pushback in places, and we’ll have discussions and give and take. But overall, we’re getting the rates that we need, and we’re going to continue to do that.”

Earlier this month, Allstate reaffirmed its commitment to increase its rates throughout 2022 because of an increase in the number of physical damage and bodily injury severity claims. Allstate CFO Mario Rizzo said the company increased its rates in March, on average, by 9.8% in 15 locations and “implemented 53 rate increases averaging approximately 8.2% across 41 locations since the beginning of the fourth quarter 2021.”

Michael DeLong, a research and advocacy associate with Consumer Federation of America, said several companies, including Progressive and Allstate, paid their largest ever shareholder dividends during the pandemic when they should have been refunding their customers’ money.

“When these insurance companies say that they need higher and higher rates to account for inflation, regulators should ask: If times are so tough that companies need to raise rates, why has there been so much inflation in executive compensation?” he said.

States urged to act

CFA argued that, because consumers and businesses are often required to buy insurance by law, states should be doing more to protect them from “excessive executive pay.” Regulatory practices in Nebraska and California could serve as models, it said.

Under Nebraska law (NE R.S. Section 44-322), carriers are required to publicly report the salaries of their executive officers. Although some companies have a practice of dividing salaries up among subsidiaries, making it difficult to get a handle on the total, CFA said Nebraska’s law “is a valuable tool for policymakers, regulators, and the public who want to know how insurance companies are spending the premium that consumers pay.”

For more information and analysis about the Nebraska filings, see the blog of Joseph M. Belth, an insurance analyst.

California’s voter-approved consumer protection law, Proposition 103, goes beyond reporting requirements, penalizing insurers for executive salaries that are found to be excessive.

Proposition 103 sets out a formula for calculating the maximum permissible executive compensation for each carrier’s top five executives, with the amount differing based on company size.

Once that number is set, carriers can choose to pay their executives as much as they’d like, but anything over the calculated maximum is used in another formula that reduces insurance rates to account for “excessive compensation.”

For example, CFA said, State Farm paid its top five executives a total of $43,199,446 in 2020, against a calculated “maximum permissible” payroll of $7,231,925. That meant that the rates paid by Californians were reduced to account for the $36 million in excess compensation.

“Notably, State Farm’s executive compensation average during that pandemic year was over twice the excess calculated in 2019 and quadruple State Farm’s 2018 excessive compensation amount,” the Alliance said.

“Americans spend a quarter trillion dollars each year on auto insurance alone and another half-trillion on other property and casualty insurance policies,” CFA’s Heller said. “States should do more to ensure that our premium dollars are not being used to fund wildly excessive pay packages for executives.”

More information

Joseph M. Belth: Executive Compensation in the Insurance Industry—Data for 2020 from 2021 Filings with Nebraska

http://www.josephmbelth.com/2021/07/no-431-executive-compensation-in.html

Images

Featured images provided by litu92458/iStock