New research finds small EVs cost-competitive with ICE vehicles, real savings best determined case-by-case

By onMarket Trends

The results of a yearlong study by the Responsible Battery Coalition (RBC) comparing electric vehicle (EV) and internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle total cost of ownership (TCO) show that smaller vehicles of both types are cost-competitive while larger ones are more expensive.

The research project was conducted with the University of Michigan Center for Sustainable Systems. To determine TCO, primary contributing factors to vehicle cost were compared as well as where, when, and for whom EVs are most cost-effective and government policies that could have the most impact on lowering EV costs.

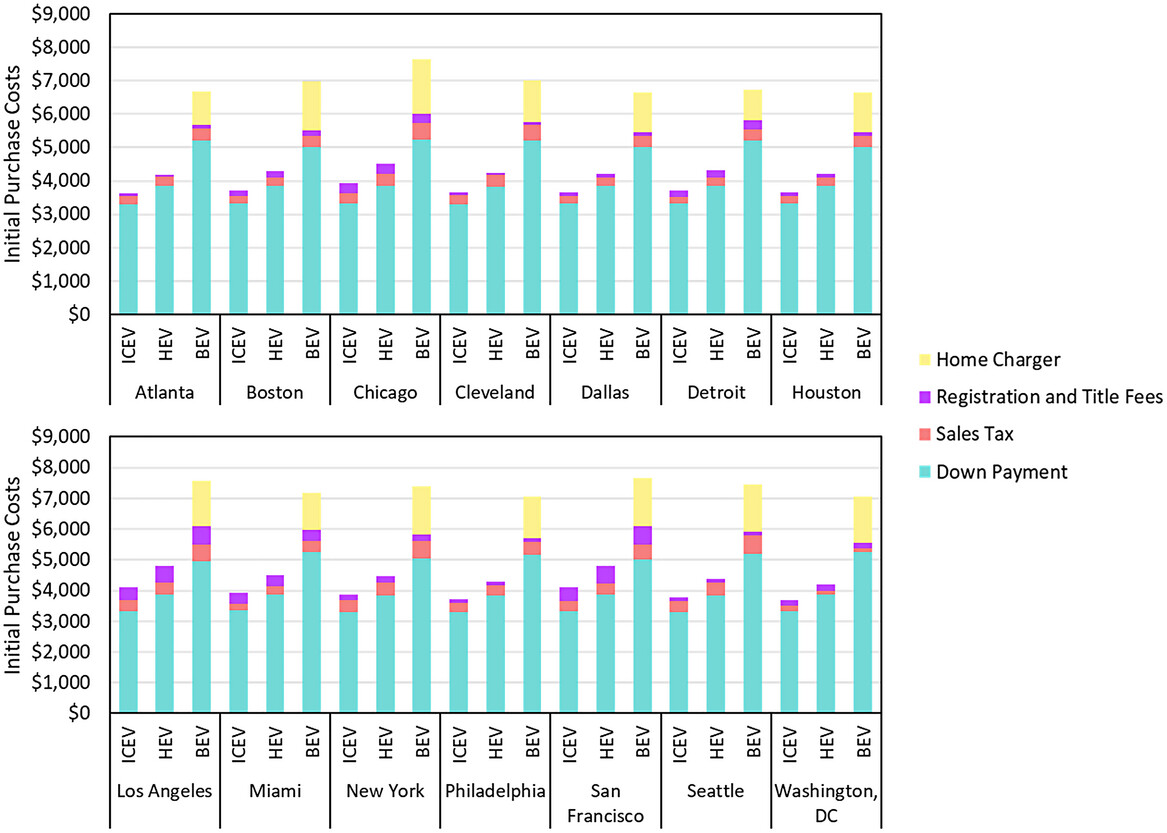

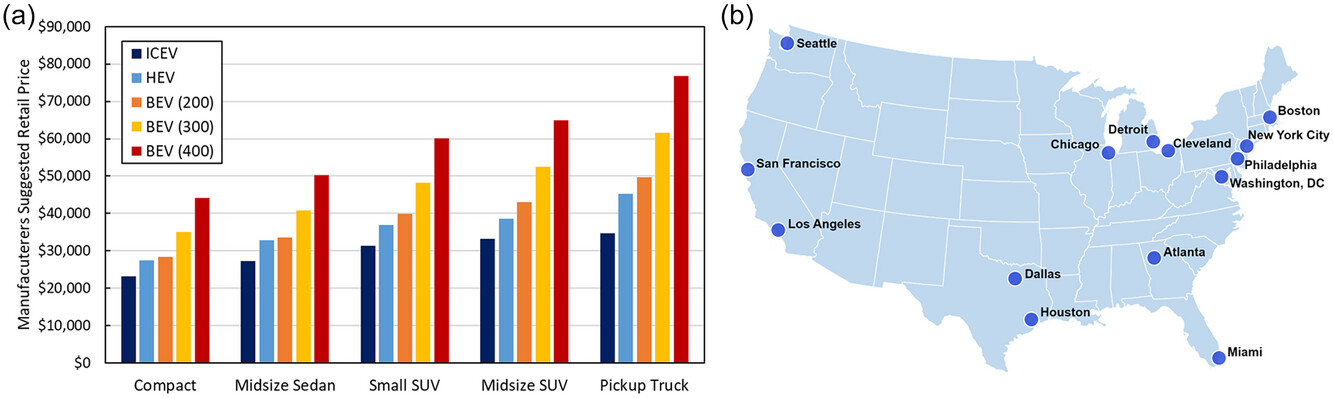

Five vehicle classes — compact sedan, midsize sedan, small SUV, midsize SUV, and pickup truck — were studied in 14 cities. The cities chosen represent major vehicle markets and a wide range of climates, electricity markets, gasoline prices, and levels of public policy incentives. The cities were Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, Manhattan, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington D.C.

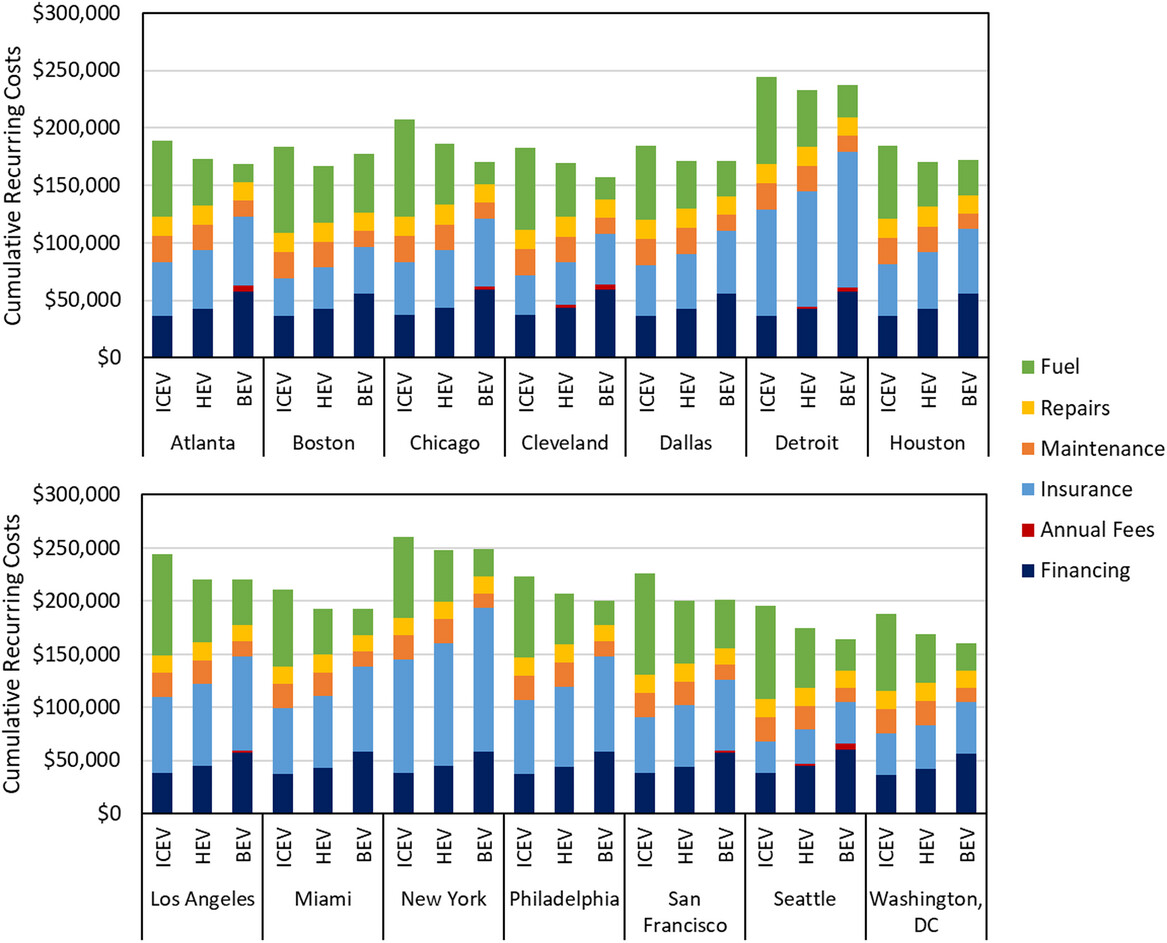

Overall, the study found that across vehicle ranges, new EVs are more competitive with new ICE vehicles in cities with low electricity prices, high gasoline prices, moderate climates, and direct purchase incentives. Home charging access, time-of-use electricity pricing, and how many miles the vehicle is driven per year were also noted as factors affecting the cost of vehicles.

More than half of the respondents to a recent AAA survey, the results of which were released in November, said they weren’t convinced EVs are worth purchasing when battery range and cost are considered. S&P Global Mobility found nearly half of global respondents to its similar survey consider EV prices to be too high.

Most S&P survey respondents said they would accept a minimum EV range below 300 miles. Forty-two percent of respondents said they’re considering an EV for their next vehicle purchase and 62% said they’re waiting until the technology improves before purchasing a new vehicle, according to S&P.

A lack of charging infrastructure is also still a concern for consumers. A mid-2023 report from J.D. Power found that 49% of people shopping for a new vehicle rejected EVs due to infrastructure concerns. The Biden Administration aims to build a national network of 500,000 EV chargers across the U.S. and for at least 50% of new car sales to be EVs by 2030 as well as net zero emissions by 2050.

According to the RBC and University of Michigan research, home charging lowers lifetime costs by $10,000 on average versus public charging stations and potentially up to $26,000, even when including the cost of installing a charger, according to the study. This is due in part to many cities having time-of-use electricity rates, offering lower prices for charging a vehicle overnight.

Across the cities studied, small and low-range EVs were found to be cost-competitive with their ICE counterparts, such as compact cars and midsize sedans, while larger or longer-range EVs such as pickup trucks are more expensive when compared to their ICE counterparts. However, midsize EVs, such as SUVs, can reach cost parity in cities with additional incentives, according to the study result

Federal incentives, such as the $7,500 federal tax credit, play a pivotal role in accelerating the break-even point between EVs and ICE vehicles, according to the study. In some cities, federal incentives can be combined with state and local incentives. However, proposed regulation changes, open for public comment through Jan. 18, could make some eligibility changes.

Vehicles that weren’t purchased before Dec. 31, 2023 and contain any battery components manufactured or assembled by a “foreign entity of concern” — the People’s Republic of China, Russian Federation, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and Islamic Republic of Iran — will be excluded. The same goes for vehicles purchased after Dec. 31, 2024.

“The UM [University of Michigan] research is essential to helping us understand the current benefits and barriers to the use of electric vehicles to power our domestic transportation fleet and decarbonize the transportation sector,” said Steve Christensen, RBC executive director. “Transportation is the second biggest cost for families in America, higher than even food and healthcare. As America increasingly electrifies, consumers need to know if buying an EV will cost more or less than an internal combustion engine vehicle, and for policymakers to understand what changes they can make to help keep transportation affordable as we lower emissions.”

In the U.S., the battery electric vehicle (BEV) sales share for light-duty vehicles increased from roughly 2% in 2020 to 4% in 2021 and 8% by May 2023, according to the study. Citing the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics, the researchers noted that, historically, gas prices rise more significantly and with greater year-to-year variability than electricity prices.

The study found that, for gasoline vehicles, refueling is most expensive in San Francisco and Los Angeles and least expensive in Houston and Dallas. For EVs, charging is most expensive in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Boston, and least expensive in Atlanta, Chicago, and Cleveland.

“EVs are currently a cheaper option in some cities and for some owners driven by policy and environmental factors outside of their immediate control,” said Maxwell Woody, lead author of the study. “As battery costs decline, we expect EVs will become cost-competitive in more locations and for more people.”

Across all vehicle classes and powertrains, there is significant cost variability depending on where a vehicle is located, the study states.

For example, “the 25-year TCO for a midsize SUV varies from $114,000 to $160,000 (ICEV, MSRP $33,000), $108,000 to $156,000 (HEV, MSRP $39,000), and $111,000 to $163,000 (BEV-300 [mile range], MSRP $52,000). Over 25 years, and across all vehicle classes, the range in TCO across cities meets (99% for BEVs) or exceeds (127% for HEVs, 143% for BEVs) the vehicle’s MSRP. Therefore, range in total cost, based on location, is of the same magnitude as the purchase price of the vehicle itself.”

The higher purchase price of EVs is a challenge for low-income households, but operating costs offer savings compared to hybrid and traditional ICE vehicles. Ensuring equitable access to home charging infrastructure, especially for renters and those in multifamily dwellings, is essential for the transition to electrified transportation, the researchers concluded.

Initial costs include a down payment for the vehicle, sales tax, various fees, and the cost of a home charger. BEVs were found to be more expensive than ICE vehicles. The higher MSRP is primarily due to the cost of the battery, which is expected to decline over time, according to the study.

“For maintenance and repair, the average time cost for ICEVs and HEVs is $93 annually, and for BEVs is $44 annually,” the study results report states. “This results in a savings of approximately $1,000 for the BEV over a 25-year lifetime (undiscounted).

“For refueling the average time cost is $103 annually for ICEVs, $52 for HEVs, and $64, $67, and $74 for 200-, 300-, and 400-mile range BEVs. This means that over a 25-year lifetime the BEV is several hundred dollars less than the ICEV, but several hundred dollars more than the HEV. These results are for one charging scenario (our base case) and would be highly dependent on individual charging patterns and income level.”

Center for Sustainable Systems Director Gregory Keoleian and senior author of the study added, “This study shows that while EVs initial purchase price is higher, households buying them instead of internal combustion engine vehicles can save money over the car’s lifetime while playing a direct role in decarbonizing transportation sector emissions. Speeding up the replacement of internal combustion engine vehicles will also make more used electric vehicles available to lower-income households who can also benefit from reduced operating and maintenance costs.”

However, it should be noted that repair costs can largely vary between older and newer vehicles as well as EVs and ICE vehicles. For example, collision repair customers are often surprised that newer model vehicles are more expensive to repair because of complex advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), on both EVs and ICE vehicles, that require much more attention and time including recalibrations. Vehicles today are often equipped with radar, lidar, sensors, and cameras that are more expensive to replace or restore.

A recent example reported by Carscoops is a Polestar 2 EV that was damaged by hitting a deer. The repair bill was $21,000. The driver thought the damage to be minor, but according to the article, that wasn’t the case.

“The Polestar EV’s bumper is pushed back and the headlight is damaged too,” Carscoops wrote. “The hood, wheel, and fender each have some damage. Interestingly, the breakdown doesn’t include a number of vital electrical parts that lie beneath the skin. Instead, the vast majority of the $21,544.82 total is labor, 90.2 hours of it to be exact. On the other hand, $10,775.40 of the gross total is parts.

“In this case, part of that labor is taking the time to safely de-energize the EV drivetrain. Many hours are quoted for work like repairing the front apron, refinishing the hood, and replacing the upper tie bar. This sort of mind-boggling repair bill might be commonplace in the not-too-distant future.”

Mitchell International’s Q3 2023 “Plugged-In: EV Collision Insights” report, released in November, found that labor for EV repairs represented nearly half the cost of total collision repair (49.66%) compared with 41% for ICE vehicles, adding up to more than six extra hours of labor per job. The additional EV costs relate to managing the high-voltage battery, according to the report.

Mitchell also found that repair costs for all EVs continue to be higher than ICE vehicles, representing a $950 difference in the U.S. and a $1,301 difference in Canada.

A much more expensive replacement cost for BEVs compared to ICE vehicles is the lithium-ion batteries. After the warranty period, battery replacement could cost between $3,400 and $17,800, depending on battery size and future battery prices, according to the RBC study. However, the researchers wrote that they expect most owners won’t have to replace their vehicle batteries.

The study concludes, “Reducing electric vehicle costs to reach parity with gasoline vehicles has long been an important goal of sustainable transportation advocates and policymakers. Whether or not this goal has been reached has no easy answer, as TCO depends on a wide range of factors. Chief among these are the size and range of the vehicle, local conditions including fuel prices and purchase incentives, and use conditions including annual mileage and charging patterns.

“…the question of BEV cost parity is best answered on a case-by-case basis, as vehicle costs are ultimately unique to each specific location and each individual user.”

The study can be viewed here.

Images

Featured image credit: deepblue4you/iStock

(a) The manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) of the 25 different combinations of vehicle class (compact, midsize sedan, small SUV, midsize SUV, and pickup truck) and vehicle powertrain (ICE vehicle, hybrid EV, 200-mile, 300-mile, and 400-mile range BEV) used in the RBC/UM study. (b) The 14 cities investigated in this study.

Upfront costs for ICE vehicle, hybrid EV, and 300-mile range battery EV midsize SUV in each city (with a down payment of 20% of the manufacturer’s suggested retail price).

Cumulative recurring costs (not discounted) for an ICE vehicle, hybrid EV, and 300-mile range BEV midsize SUV in each city over a 25-year vehicle lifetime.

All graphics and charts provided by RBC and UM with permission for publication.