Ohio auto body shop loses appeal of attorney fees, DV over incorrectly repaired Nissan Maxima

By onBusiness Practices | Legal | Repair Operations

An Ohio appellate court on Friday rejected an auto body shop’s arguments related to attorney’s fees, diminished value and a new trial decision in a $105,462.59 case involving what a jury found to be an improperly repaired Nissan sedan.

The unanimous First District Appellate Court decision in favor of the vehicle owner also demonstrates to Ohio collision repairers the value of following OEM repair procedures — which the jury in the original case found to have been ignored.

Williams v. Sharon Woods Collision involved a 2010 Nissan Maxima that plaintiff Jeremy Williams brought to Sharon Woods Collision for a repair in 2012.

The shop is no longer under the same ownership as at the time of Williams’ repair. “We don’t have anything to do with it (the case),” a representative of what is now Sora’s Sharon Woods Collision Center & Service said Monday.

All references to “Sharon Woods Collision,” “SWCC” etc. throughout this story and the litigation refer to the facility under prior owner Bernie Burckard, not Sora’s Sharon Woods (which is owned by the Sora family).

Messages left for counsel representing the old Sharon Woods Collision mid-Monday afternoon had not yet been returned.

“SWCC represented to consumers that it performed all repairs to automotive specifications with the intent to restore vehicles to their preloss conditions, and that its technicians were trained and certified in the latest automotive advancements,” Judge Russell Mock wrote for himself and Judges Dennis Deters and Marilyn Zayas. “It also represented that it had gold class certification by I-CAR, a recognized industry training organization, and that it repaired vehicles according to I-CAR guidelines.”

Following a post-repair inspection, Williams had sued Sharon Woods Collision alleging “unfair, deceptive and unconscionable acts in connection with a consumer transaction,” fraud and a violation of the “Motor Vehicle Repair Rule,” according to Mock.

“The evidence at trial showed that in repairing the car, SWCC had used structural bonding adhesive to attach panels to the car, a method which was not approved by the manufacturer or appropriate under I-CAR guidelines,” Mock wrote. “Williams presented the testimony of three experts, who all testified that the car was not repaired in accordance with Nissan’s specifications or I-CAR guidelines, that some repairs in the estimate were not completed, and that the some of the repairs had been done in an unworkmanlike and sloppy manner.

“The experts also testified that due to the use of the bonding adhesive and the shoddy repairs, the car was unsafe to drive because it was no longer crashworthy. Williams stated that he had stopped driving the car due to its unsafe condition. The experts also testified regarding the car’s diminished value after the shoddy repairs, with one stating that it was worthless post repair.”

The jury concluded that the shop violated the Consumer Sales Practices Act and the Motor Vehicle Repair Rule but hadn’t committed fraud.

According to Mock:

The jury found in favor of Williams on both of his CSPA claims. It found that SWCC had (1) represented that the repair of the car had sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits that it did not have; (2) represented that the repair was of a particular standard or quality that it was not; (3) represented that the repair had been performed in accordance with a previous representation, when it had not; (4) represented that it had a sponsorship, approval, or affiliation that it did not have; (5) failed to perform the repairs in a workmanlike manner; (6) stalled and delayed or attempted to avoid a legal obligation; (7) charged for labor based on an estimate of time, instead of the actual time to perform the repair; (8) returned the car to Williams in an unsafe condition; (9) failed to provide the consumer with an itemized list of repairs and failed to tender replaced parts; and (10) committed other deceptive and unfair practices.

Williams sued in 2014, and the verdict and court judgment came in 2016.

The jury awarded damages of $8,079.78, but Hamilton County Court of Common Pleas Judge Mark Schweikert agreed to Williams’ motion for triple damages on certain items, attorneys fees and costs — which added tens of thousands of dollars more to the shop’s tab.

The shop sought a new trial, failed to achieve it in 2016 and 2017 (the 2016 denial by a prior judge hadn’t been served) and appealed in 2017.

Diminished value

Sharon Woods Collision argued that the trial court shouldn’t have allowed the jury to consider diminished value, nor should it have rejected a request for a directed verdict, according to Mock.

“In both of those cases, the courts held that the owner of a damaged vehicle may recover the difference between its market value immediately before and immediately after the collision,” he wrote. “The owner of a vehicle may prove and recover the reasonable cost of repairs provided that the recovery may not exceed the difference between the market value of the vehicle immediately before and after the collision.”

The shop had argued citing the cases that Williams didn’t demonstrate how much the car was worth after the crash but before the repair.

But the appellate court called those precedents inapplicable: “Neither involved claims against the repair shop for shoddy repairs under the CSPA. … The purpose of R.C. Chapter 1345, the CSPA, is to protect consumers from suppliers who commit deceptive or unconscionable sales practices. It is a remedial act that courts must liberally construe in favor of the consumer.”

Williams’ expert witnesses offered testimony how much it would cost to repair the car correctly and the vehicle diminished value, according to Mock.

“Larry Montanez testified that the cost to re-repair the vehicle was $11,000,” Williams wrote to the appellate court. “Mike Anderson testified that the Vehicle was worthless post repair. And, David Williams testified that the diminished value of the Vehicle due solely to the shoddy repair was $9,337.50.”

“Another expert (Williams) testified in depth about how he arrived at his figure for diminished value,” Mock wrote. “He started with the total post-repair diminished value and subtracted the inherent diminished value due to the accident, which he calculated using a standard rate of 30 percent of the car’s pre-accident value. The result was the diminished value of the car due solely to the improper repairs. This evidence was relevant to determining the car’s diminished value and was proper under the CSPA definition of damages.”

Based on this, “reasonable minds” would disagree on the diminished value amount and the case could be sent to a jury, Mock wrote. The Hamilton County Court of Common Pleas was right not to grant the shop a directed verdict, he wrote.

Attorney’s fees and costs

This part of the appellate decision is key, as it accounted for the bulk of the $105,462.59 awarded Williams.

“The total jury award in this case was $8,079.78,” Schweikert wrote in 2016. “At first glance one might think that the Plaintiffs request of a total of $86,726.62 in fees and costs is an outrageous sum in relationship to the jury award. However, in the Bittner case, Chief Justice Moyer discarded that concern immediately stating, ‘At the outset, we reject the contention that the amount of attorney fees awarded pursuant to R.C. 1345.09(F) must bear a direct relationship to the dollar amount of the settlement, between the consumer and the supplier.'”

Moyer had quoted language declaring the point of adding the attorneys fees to the consumer act “‘to prevent unfair, deceptive, and unconscionable acts and practices, to provide strong and effective remedies, both public and private, to assure that consumers will recover any damages caused by such acts and practices, and to eliminate any monetary incentives for suppliers to engage in such acts and practices.'”

Schweikert called the fees reasonable, and rejected Sharon Woods’ argument that “the only claims for which fees can be awarded are for those claims where the jury found that the defendant acted knowingly,” as he summarized it.

The jury only found that Sharon Woods knowingly “‘Failed to provide the consumer with written itemized list of repair with identity of the individual; Failed to tender replaced parts,” according to Schweikert.

But the attorneys fees awarded could be extended to encompass work proving any violation of the law, according to Williams and Schweikert.

“Plaintiff argues that the facts supporting the various claims in this case are entwined and stem from a common core of facts and related legal theories and cites numerous cases where the court did not separate fees and expenses according to a knowingly finding,” Schweikert wrote. “Also that the plain reading of the CSPA law at R.C. 1345.090(F) would allow fees and expenses if the supplier has knowingly committed a violation, interpreting the law as to not require a sorting or fees and expenses.”

Schweikert agreed that “the Plaintiff has overwhelmingly prevailed on his claims with the jury,” which found Sharon Woods violated the Consumer Sales Practices Act in a variety of unintentional and intentional ways:

1. That the Defendant did represent that the repair had sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses, or benefits that it did not have;

2. That the Defendant did represent that the repair was of a particular standard or quality that it was not;

3. That the Defendant did represent that the repair had been performed in accordance with a previous representation, when it had not;

4. That the Defendant did represent that it had a sponsorship, approval, or affiliation that it did not have;

5. That the Defendant did fail to perform repairs in a workmanlike manner.

6. That the Defendant did stall and delay and avoided or attempted to avoid a legal obligation;

8. That the Defendant did repair the vehicle and return it to the Plaintiff in an unsafe condition;

9. That the Defendant did, in connection with the repair, represent that the repairs were performed when such was not the fact;

10. That the Defendant did , in connection with the repair, fail to provide the Plaintiff with a written itemized list of repairs performed which identified the individual performing the repair or service;

11. That the Defendant did, in connection with the repair, fail to tender to the Plaintiff any replaced parts. (Minor formatting edits.)

The appellate court noted Friday the Ohio Supreme Court had ruled that attorney fees should only apply when CSPA claims could be separated from a claim under some other law.

“But when it is not possible to divide claims in that fashion, such as when claims not covered under the CSPA involve a common core of facts with claims arising under the CSPA, then the court may award attorney fees for all time reasonably spent pursuing all claims,” Mock wrote.

The appeals judges “cannot hold that amount of the fees was so high or so low as to shock the conscience. Therefore, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in awarding attorney fees,” Mock wrote.

The decision and the Ohio Supreme Court precedent cited seems as it should put Ohio repairers on notice that intentionally violating any part of the Consumer Sales Practices Act could trigger pricey attorney fees for all the unintentional violations as well.

One wonders if a shop aware of the existence of OEM repair procedures but intentionally opting not to follow them would be considered knowingly violating the law — and therefor triggering the fees — when the shop delivered the vehicle.

According to the law, it’s a violation to say “That the subject of a consumer transaction has sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses, or benefits that it does not have”; “That the subject of a consumer transaction is of a particular standard, quality, grade, style, prescription, or model, if it is not”; and “a misleading statement of opinion on which the consumer was likely to rely to the consumer’s detriment.”

The only way to avoid the attorney’s fees would then seem to be outright incompetence that there’s a right way to fix the car — which isn’t a ringing endorsement for the repairer, either.

Finally, Mock ruled that Williams’ ability to sell the Maxima to a dealership — which in turn made $11,000 selling it to someone else — didn’t mean a new trial was warranted.

Sharon Woods Collision alleged “’Mr. Williams appears to have sold the vehicle without disclosure’ of its condition,” according to Mock. But that wasn’t the case, according to Williams.

“Williams responded with affidavit in which he acknowledged selling the car to the dealer in the same condition it was in at trial,” Mock wrote. He further stated that he fully disclosed all issues with the car, including that the fact that he had sued the body shop, that the car was still disassembled from the last inspection by his expert, and that he had left it overnight so that the dealer could inspect it.”

That’s not misconduct, the appellate court concluded.

“SWCC contends that these facts undermine the testimony of Williams’s expert that the car had no value and that it was unsafe to operate,” Mock wrote. “But SWCC presented its own expert testimony and had an opportunity to rebut Williams’s evidence regarding value, and the value that a third-party obtained in a sale after-the-fact was irrelevant to that determination. …

“SWCC argues that Williams had a duty to mitigate his damages, and that its evidence showing that he sold the car after trial proves that he did not. But SWCC had the opportunity to present evidence regarding the value of the car, and the jury was instructed on the duty of mitigation. The events after trial did not change the fact that no error of law had occurred.”

Images:

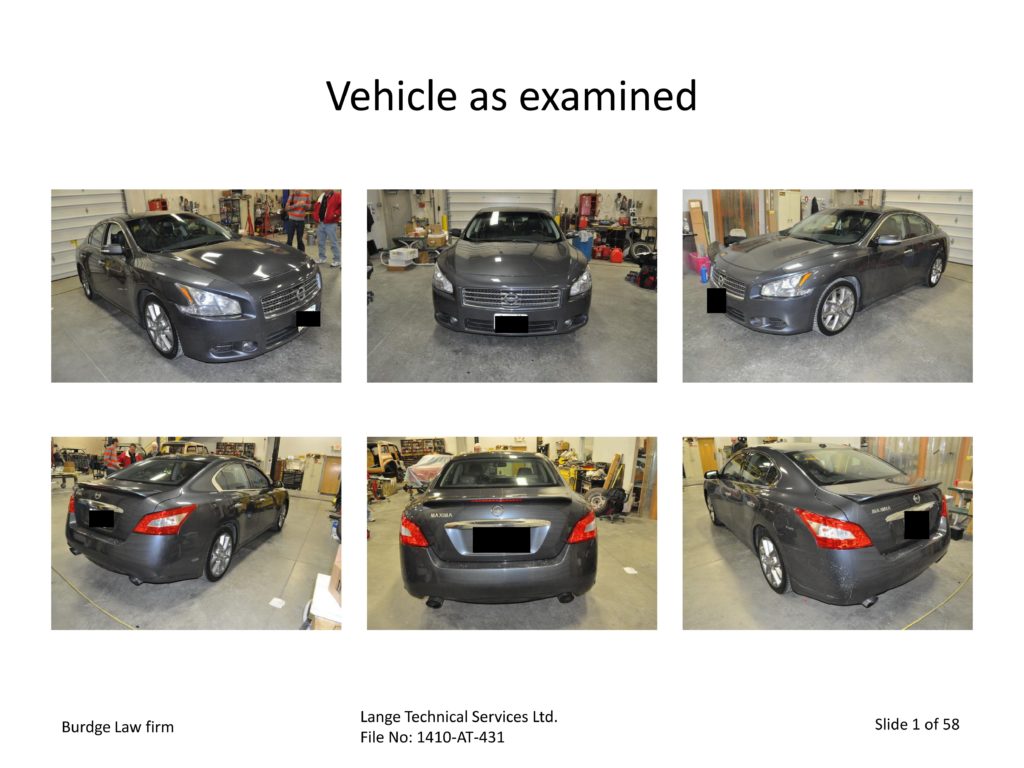

An Ohio appellate court on Friday rejected an auto body shop’s arguments related to attorney’s fees, diminished value and a new trial decision in a $105,462.59 case involving an allegedly incorrectly repaired Nissan sedan. (Provided by Lange Technical Services)

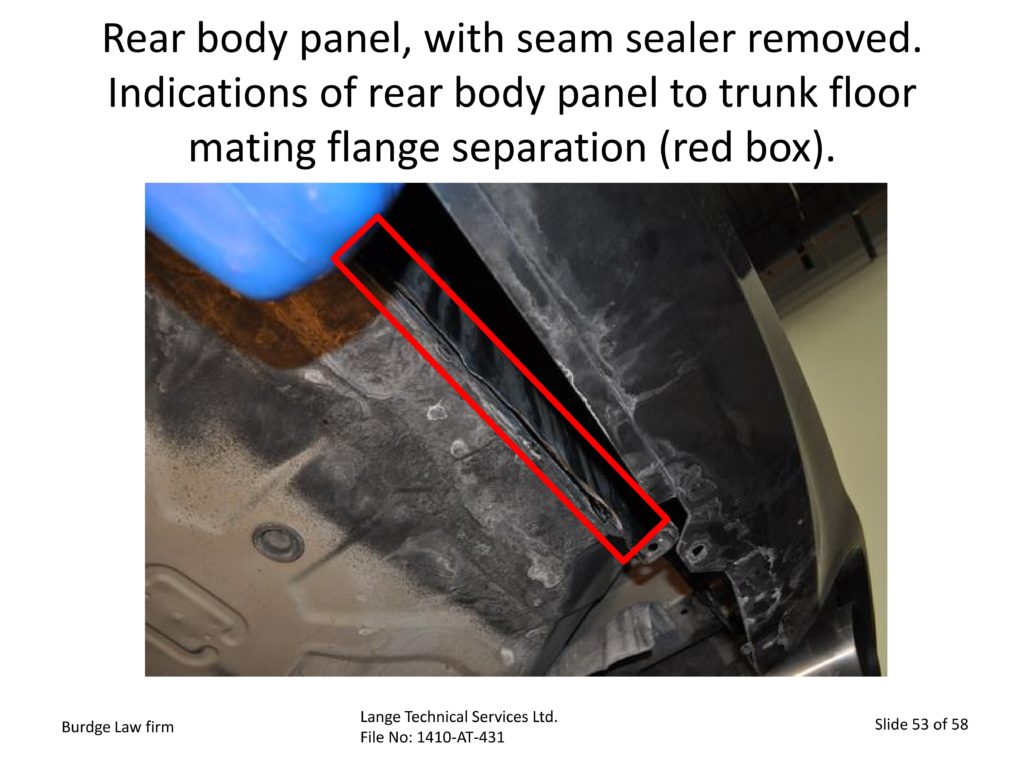

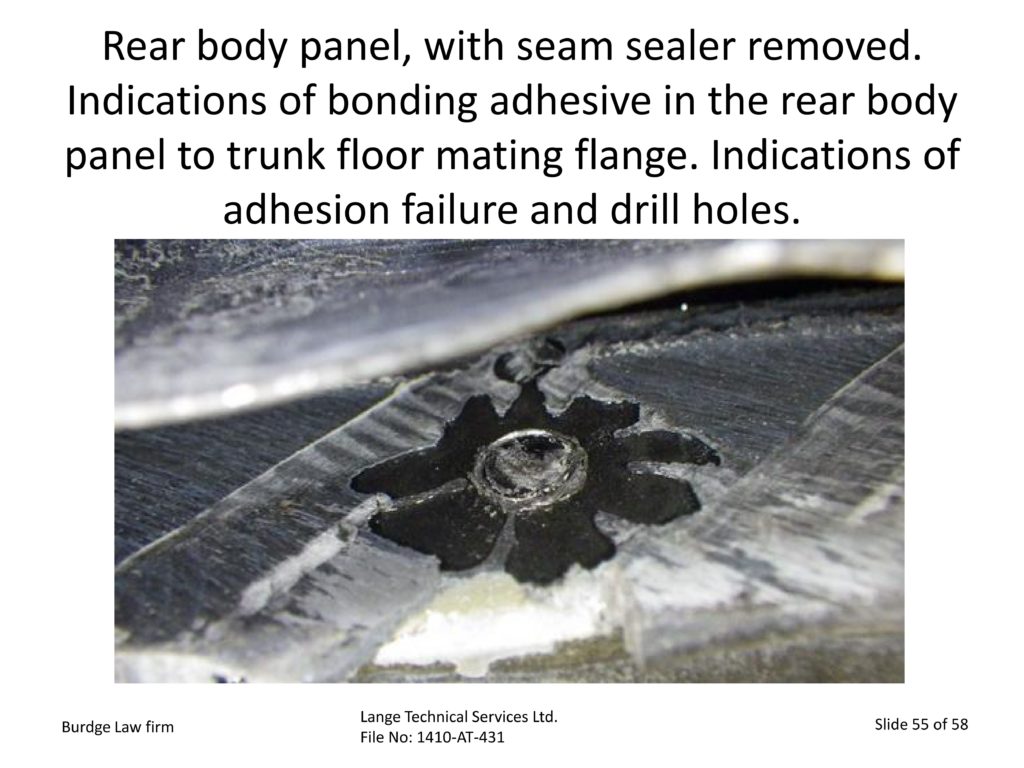

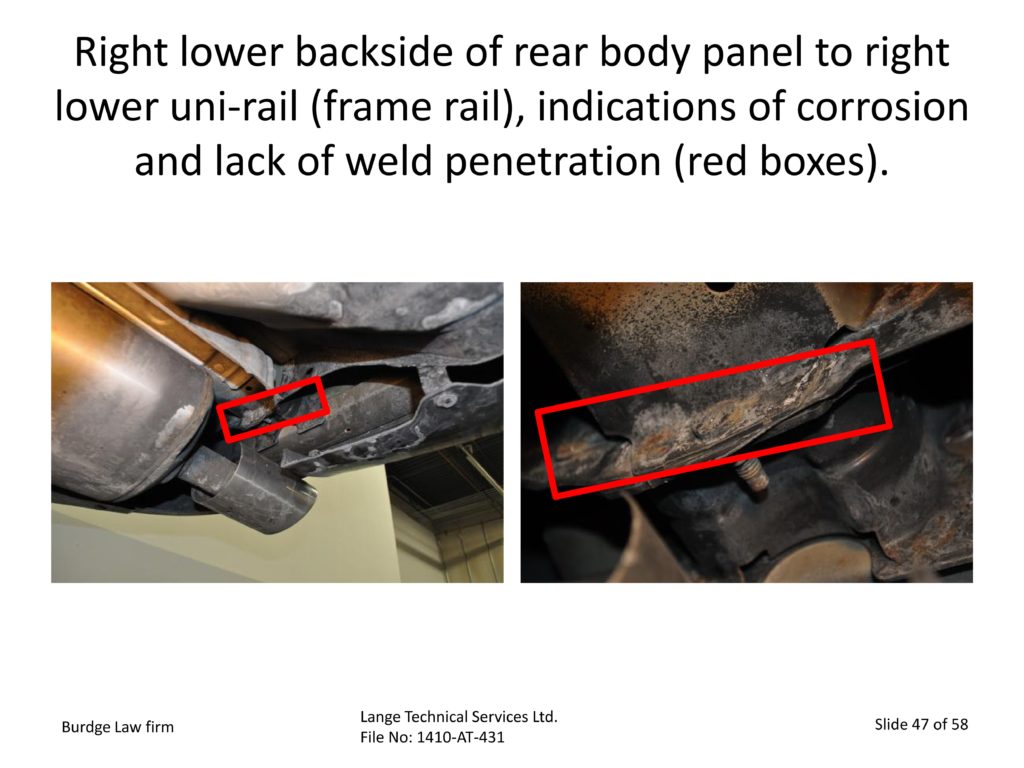

A 2014 report to attorney Beth Wells (Brudge Law Office) by Larry Montanez and Jeff Lange of Lange Technical Services describes joining issues on a 2010 Nissan Maxima. (Provided by Lange Technical Services)

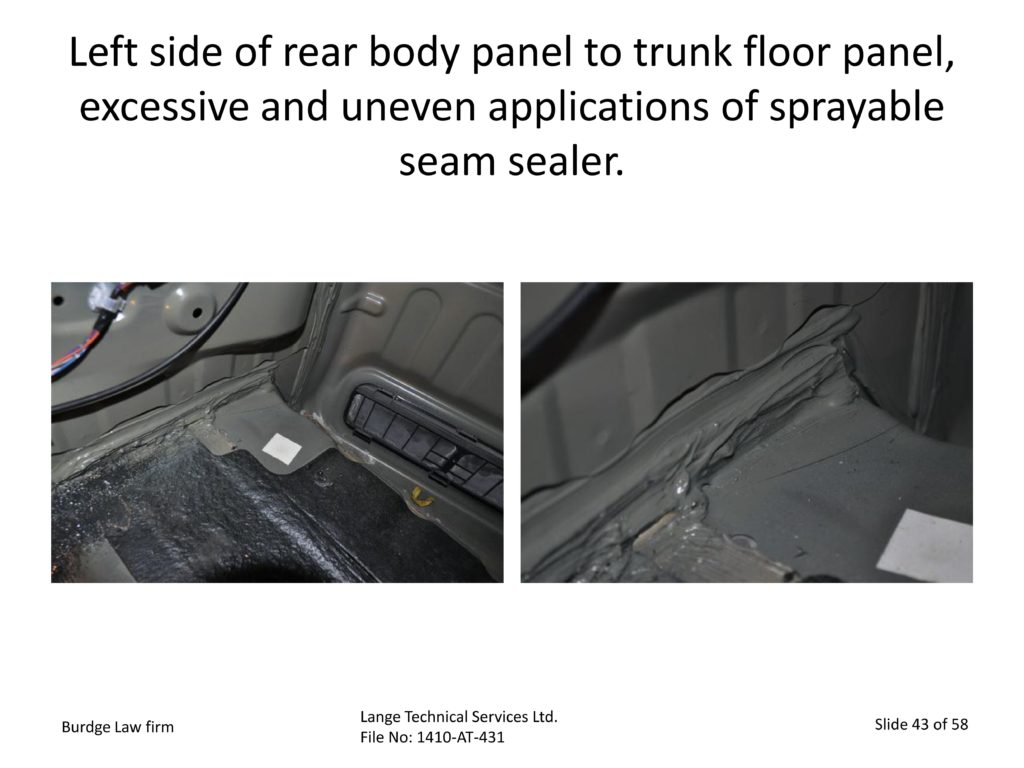

A 2014 report to attorney Beth Wells (Brudge Law Office) by Larry Montanez and Jeff Lange of Lange Technical Services describes incorrect seam sealer on a 2010 Nissan Maxima. (Provided by Lange Technical Services)