‘Who Pays?’: Insurers often cover seat sensor resets, other calibrations

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Insurance | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

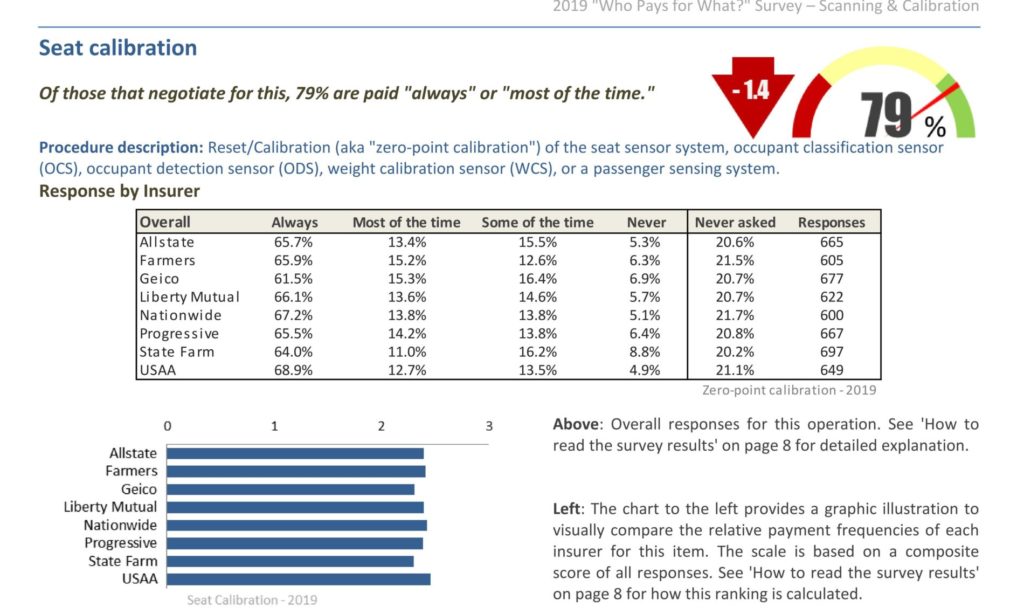

Eight of the nation’s largest insurers consistently pay for calibrations, including resets of occupant sensing systems, according to the latest “Who Pays for What?” study.

However, despite 79 percent of shops reporting insurers paying for occupant sensor calibrations all or “most of the time” shops bill for it, a fifth of the 600-plus repairers polled in October 2019 never asked to be paid for the operation.

One hopes the facilities are still completing the work, for the calibrations are necessary to ensure the vehicle’s airbags function as intended. An airbag can be more harmful than helpful for small children and adults, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Occupant classification sensors use inputs like weight to determine if a party is too small for an airbag and prevent the supplemental restraint system from deploying.

An improperly calibrated sensor can lead the car to think a child is an adult or vice versa, potentially jeopardizing either demographic.

As Collision Advice CEO Mike Anderson explains in the report:

“Seat calibration” is the process of resetting or calibrating a vehicle’s seat sensors, which automakers may refer to as occupant classification sensors (OCS), occupant detection sensors (ODS), weight calibration sensors (WCS), or a “passenger sensing system.” It’s a critical step because in the event of an accident, how the airbag deploys may vary depending on whether I’m the one driving the vehicle – at 180 pounds – versus my sister driving the vehicle at 102 pounds. In some cases, the system tells the vehicle not to deploy some of the airbags if there’s no passenger in the vehicle, or if the passenger is a small child.

You must research these OEM repair procedures every time because they vary by automaker and even between models. Some Toyotas, for example, require a seat calibration after any accident, even if the vehicle was parked and unoccupied when it was hit. But on other Toyota models, a calibration is required only if a related diagnostic trouble code (DTC) has been set.

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach. Some of the systems may even reset themselves after a test-drive. So you have to check the procedures to know what the particular requirements are for the specific vehicle you are repairing. I find one of the best ways to start researching seat calibration requirements is by checking the vehicle owner’s manual. It will tell you what the automaker calls the system, and can help you explain the importance to the customer and insurer. (Emphasis added.)

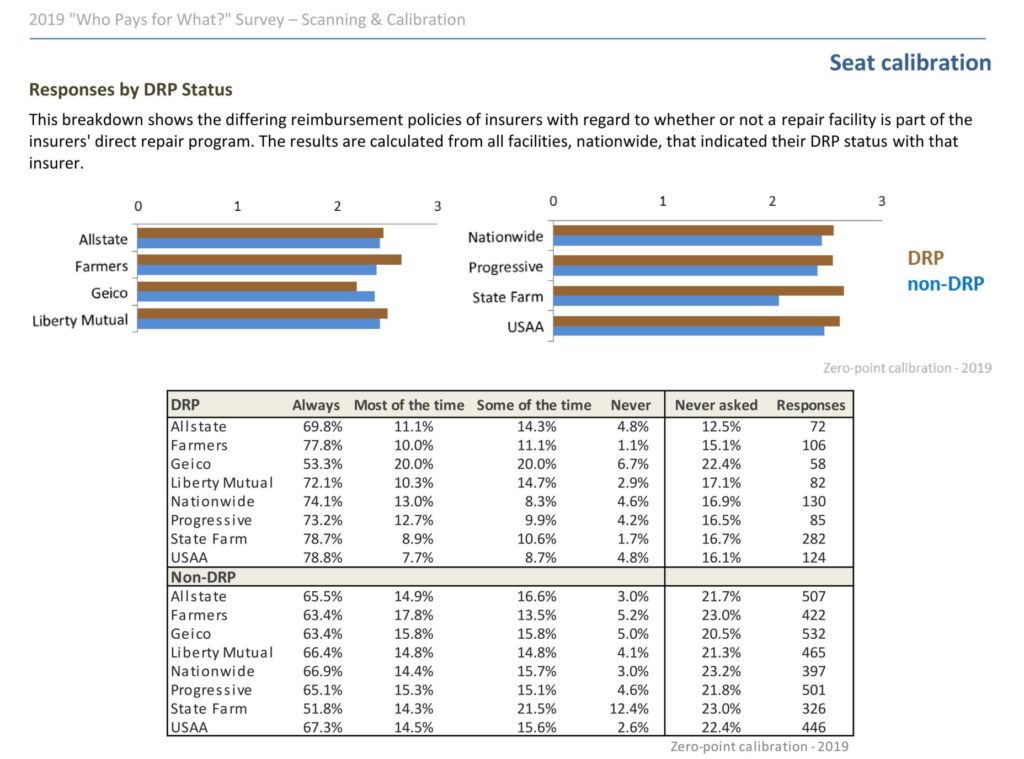

The study also examined insurers’ willingness to cover charges for direct repair program network and non-DRP shops. It found State Farm posting the widest difference in behavior here with its reduced willingness to reimburse the bill at non-DRP shops than it was at Select Service facilities.

About two-thirds of the 326 non-DRP shops polled reported State Farm paid always or most of the time — compared to nearly 88 percent of the 282 DRP shops polled. 12.4 percent of the non-DRP shops said State Farm “never” covered the charge — compared to just 1.7 percent of DRP facilities. (The margin of error was 3.4 percent on questions receiving answers from all 805 respondents.)

The survey results carry lessons for consumers as well as body shops. After all, collision repairers are actually billing customers, not insurers. Those consumers must pay the shops and seek reimbursement from insurers.

Help the collision industry by taking the current “Who Pays for What?” survey focusing on refinish operations before Feb. 1. All answers are kept confidential; data is published only in the aggregate.

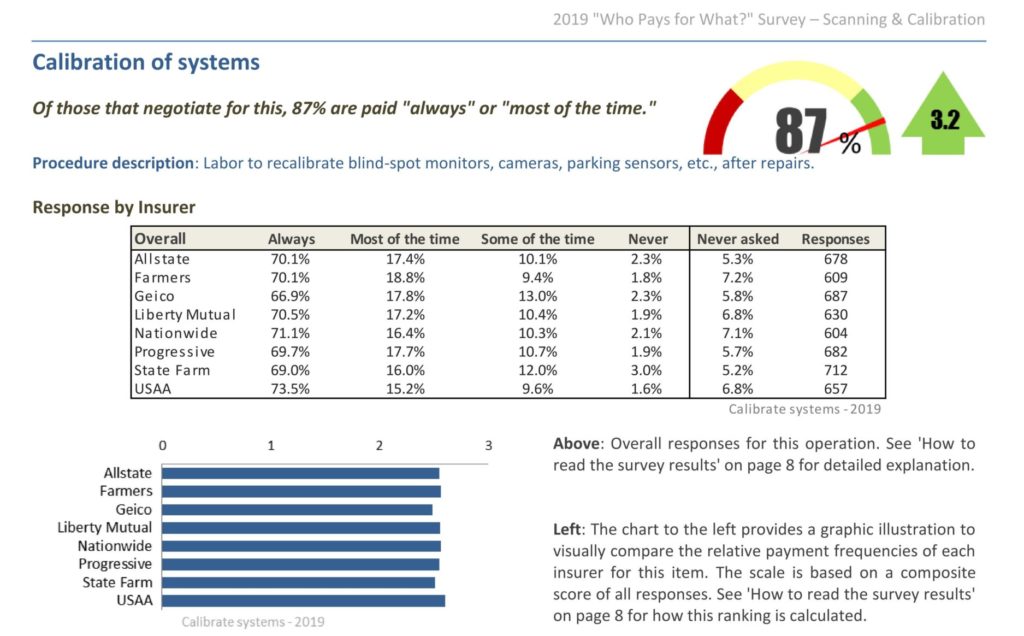

Another question asked about advanced driver assistance system calibration, describing it as “Labor to recalibrate blind-spot monitors, cameras, parking sensors, etc., after repairs.”

87 percent of shops said insurers were always or mostly covering those bills when requested. Unlike the 20-plus percent of shops who never asked to be paid for seat calibration, the percentage of shops who never charged for the work was in the single digits.

“Calibration processes vary widely from vehicle to vehicle and from system to system,” Anderson wrote. “Some blind-spot monitoring systems, for example, require a test-drive to self-calibrate. Others require the use of a scan tool and a target. Other systems that can require calibration include adaptive cruise control, parking sensors, and back-up or other cameras. How many times do we remove a mirror from a door for paint purposes? Those often include cameras that require calibrations.”

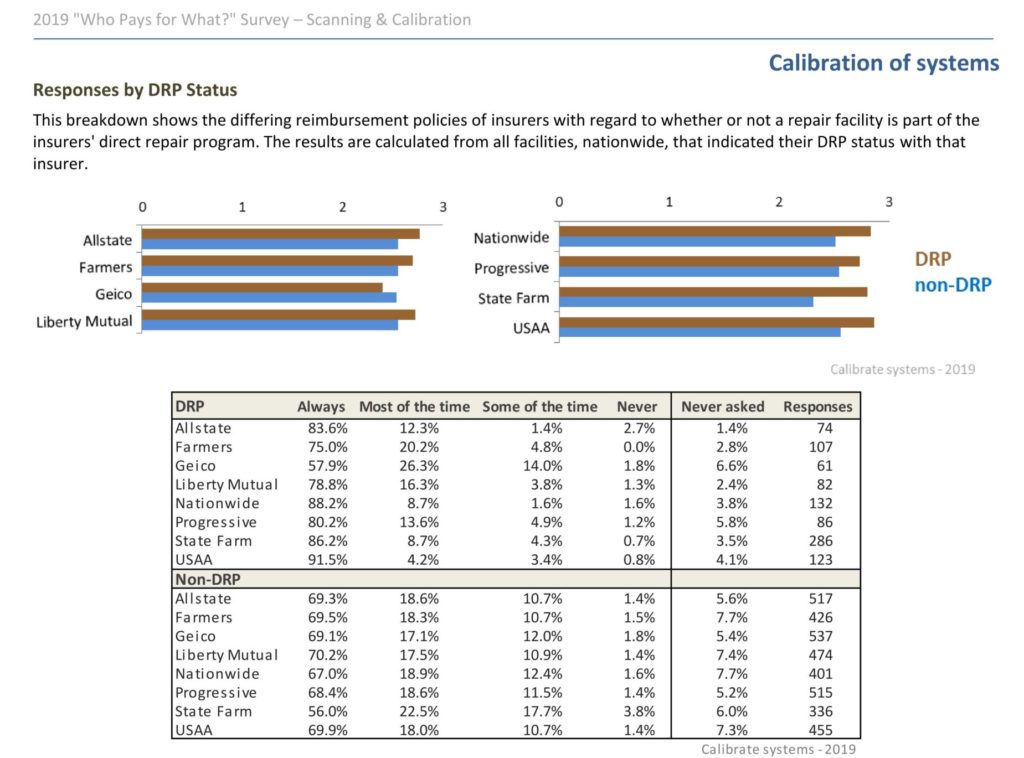

State Farm also posted the widest difference here in willingness to pay DRP shops compared to non-DRP shops.

CCC data

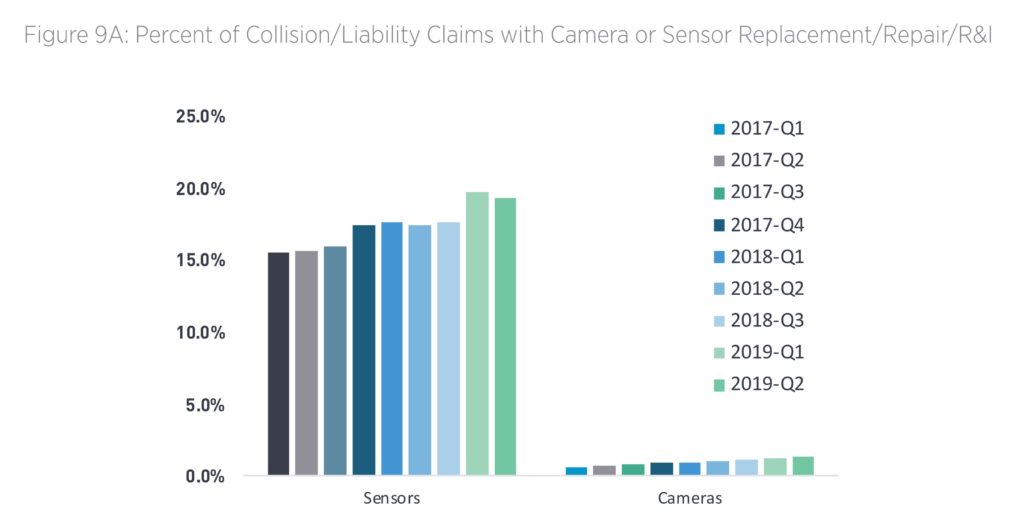

CCC director and lead analyst Susanna Gotsch wrote in a study of data between the first quarter of 2017 and 2Q 2019 that calibration operations typically see an addition of 0.2-0.6 hours of labor.

“When a part such as a distance sensor is replaced, additional database labor time of 0.2 to 0.6 hours is commonly added as an entry such as ‘FRONT BUMPER Add for distance sensor’,” Gotsch wrote in a September 2019 piece. “In addition to this, some repairs include separate manual entries for calibration, depending on the components damaged or the vehicle repair requirements. The specific parts requiring calibration are not always identified clearly or at all but, not surprisingly, the majority identify a specific ADAS feature such as blind-spot monitoring sensor, distance sensor, camera, parking sensor, lane departure, adaptive cruise control, as well as mechanical parts such as occupant sensors, steering angle sensors and tire pressure monitoring sensors, and finally parts such as headlamps.”

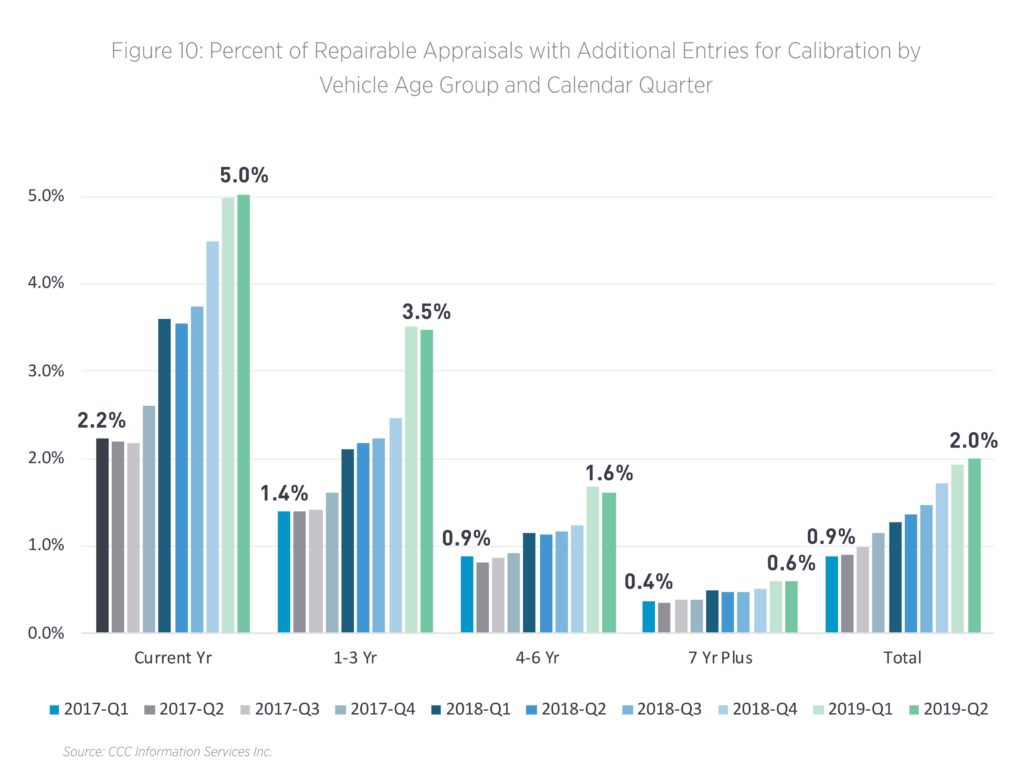

The 2 percent of vehicles with entries for terms like “‘calibration’, ‘re-program’, ‘flash’, etc.” was up from 0.9 percent in the first quarter of 2018, according to Gotsch.

The cost of a calibration was all over the place in the second quarter of 2019. Gotsch reported that some line items involved “not just the cost of calibration, or a fee to ‘Drive to and from calibration’, but the cost of additional components that may have been found to need replacement during the calibration.”

The average second-quarter calibration fee was $219 — up from $172 in the second quarter of 2017. The standard deviation two years prior was $214, compared to $236 today. The maximum fee between April and June of this year was $5,316 for “Dealer Distance Sensor Reprogram,” compared to a peak of $6,250 for “Reprogram Headlamps at dealer” in the second quarter of 2017.

Also of note in the CCC report: Vehicles 7 years of age or older even saw calibration operations, so repairers and insurers shouldn’t jump to any conclusions based on vehicle age. The percentage of repairable 7+ vehicles with recorded calibration operations rose from 0.4 percent in the first quarter of 2017 to 0.6 percent in the second quarter of 2019.

More information:

CCC, Sept. 4, 2019

Images:

Data from an October 2019 “Who Pays for What?” survey by Collision Advice and CRASH Network. (Provided by Collision Advice and CRASH Network)

Calibration operations could only be found on 2 percent of second-quarter 2019 repairable appraisals, and only 5 percent for the current model year. That’s an increase over the 0.7 percent of appraisals with calibration CCC earlier reported in a 2019 “Crash Course” analysis of a year of data (November 2017-October 2018). (Provided by CCC)

The average second-quarter 2019 calibration fee found by CCC was $219 — up from $172 in the second quarter of 2017. (Provided by CCC)

The passenger seat of a 2020 Toyota Corolla SE is shown. (Provided by Toyota)