Appeals court to reconsider GM fender patent lawsuit

By onCollision Repair | Legal

In a case that could determine whether automakers are allowed to patent parts considered obvious, a U.S. appeals court said it will reconsider its previous decision to uphold a GM car fender patent.

The appeals court’s decision marks a victory for LKQ. Corp, which is petitioning for a review of GM’s ‘625 patent on the grounds is invalid because it was predated by at least two preexisting and similar designs.

An appeals court previously rejected LKQ’s argument, ruling that it had “not demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence the ‘625 patent was anticipated or would have been obvious before the effective ruling date.”

It took legal action against GM after a license agreement, which gave LKQ access to many of the OEM’s design patents, expired in February 2022 following a “breakdown of renewal negotiations”.

When it did, GM sent letters to LKQ’s business partners “alleging that the now unlicensed LKQ parts infringe its patents,” according to legal filings.

Its argument essentially boils down to whether GM should have been allowed to patent a design that was considered obvious. It means that the idea behind the patent was already familiar to experts and the general public, and should as a result not have been protected as intellectual property.

In January an appeals board rejected LKQ’s argument that GM’s patent was invalid, acknowledging that while there were some similarities between its fender design and others, there were a number of “key differences.”

It said GM’s wheel arch shape, door cut line, protrusion, first and second creases, inflection line and concavity line contributed to different appearances in its design. The board also found that LKQ lacked evidence to show that consumers might confuse GM’s part with similar items that were previously patented.

A third reason for the appeal’s rejection was because its patent was designed for a specific part of the vehicle, as opposed to the whole vehicle. As a result it found ordinary observers were unlikely to confuse its part with others.

“GM argues that the ordinary observer must be the person who purchases that part or is otherwise sufficiently interested in that part, not necessarily the vehicle as a whole,” the appeal’s court ruling says. “GM further argues that, regardless of the ordinary observer, the Board’s holding that the claimed design of the ’625 patent is not anticipated by [a previous patent] was supported by substantial evidence.”

Finally, the board said it applied the Rosen and Durling test, referencing separate court cases from 1982 and 1996, which tests a patent’s obviousness.

“The Board found that LKQ failed to identify a sufficient primary reference, and therefore failed to prove obviousness by a preponderance of the evidence,” the ruling said.

LKQ had appealed the case for two reasons:

-

- It contended that “the Board erred in finding that the ordinary observer would include only retail consumers who purchase replacement fenders and commercial replacement part buyers, and, ultimately, in finding no anticipation”; and

- “That the Rosen and Durling tests on which the Board relied in its obviousness analysis have been implicitly overruled by the Supreme Court’s decision in [other cases].”

GM said in its own court filing that its fender design was “not obvious,” and that nothing in LKQ’s petition “merits rehearing.”

“This is a highly factual case about GM’s innovative front fender design claimed in the ’625 Design, and the Board’s supported finding that LKQ did not

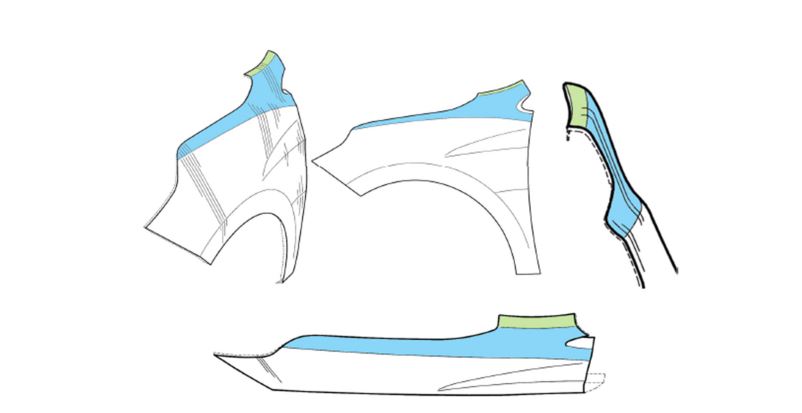

meet its burden on anticipation or obviousness,” the OEM said. “GM is a leader in vehicle design and automotive engineering. One of its innovations relates to a unique design for a car’s front fender, used in GM’s 2018-2020 Chevrolet Equinox. Appx0882-0884.

“This design includes a cohesive set of features that contribute to its unique overall appearance, including a prominent wheel arch, a smooth, curved door cut line and protrusion, and distinctive sculpting and creases. These features evoke a smooth, continuous, and curved look—as opposed to, for example, a more angular design like the prior art.”

LKQ’s appeal was supported by The Automotive Body Parts Association (ABPA), which in a legal filing urged the court to review whether the “reference requirement of Rosen is incompatible with Supreme Court precedent and other pre-Rosen precedents, and to determine what principles are appropriate for determining obviousness in the design patent context.”

“When patents are allowed on automotive part designs that should be considered obvious, it harms consumers and poses a significant risk to the automotive repair parts supply chain in the United States,” ABPA said. “Consumers rely on automotive parts to repair their vehicles and bring them to pre-accident condition.

“Allowing patents on obvious designs leads to higher motor vehicle repair costs due to lack of competition to the Original Equipment Manufacturers. Additionally, consumers face higher automotive insurance costs due to more expensive parts pricing as well as a significant time delay in getting their vehicles repaired due to fewer options in the supply chain.”

Separately, the American Property Casualty Insurance Association and the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies submitted a brief saying the Rosen, Durling test has allowed OEMs to “obtain and enforce design patents on insignificant part-variations year-over-year in a crowded field.”

“These design patents, which would otherwise be deemed obvious to an ordinary designer, unfairly exclude competitive aftermarket repair parts from the marketplace and thereby substantially increase repair costs,” its joint brief said.

“By increasing the overall costs of repairs, the lack of competitive repair parts affects not only the cost of parts but also the decision of whether to repair or replace a damaged car. Higher part costs mean higher repair estimates, and if a repair estimate exceeds the value of a vehicle, it is considered a total loss.”

On June 30, the decision was called into question when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit granted a rehearing in what Reuters described as a “rare step” for the court.

It means LKQ’s appeal has been reinstated and that both it and GM will have another chance to make their arguments. The rehearing will also address whether the Rosen and Durling test should be used to determine a patent’s obviousness, and whether a design should be considered unpatentable based on similar, previously-published designs.

Both companies were given 45 days, with the clock starting June 30, to file briefs in response to the order. A date for attorneys to make oral arguments has not yet been set.

GM did not responded to a Repairer Driven News queries by deadline.

The case is being revisited as a U.S. congressman pushes for legislation that would significantly reduce design patent protections for OEM collision parts.

The Save Money on Auto Repair Transportation (SMART) Act, introduced by Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) would reduce the amount of time car manufacturers can enforce patent designs on repair parts against non-OEM parts suppliers from 14 years to 2.5 years. The bill is largely the same as previous versions introduced in prior sessions of Congress.

A news release announcing the proposed bill said the current patent term “prevents aftermarket manufacturers from making or selling external collision repair parts, which drives up repair costs by limiting consumer choice, crowding out competition, and leading to higher insurance rates and fees.

Images

Featured image credit: JHVEPhoto/iStock

Secondary image: GM’s ‘625 patent/Courtesy of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit