‘We gotta get back to the basics’: Auto body repair weld quality could be issue in industry

By onBusiness Practices | Education | Market Trends | Repair Operations | Technology

A welding panel Nov. 7 during the SCRS OEM Collision Repair Technology Summit raised questions about the quality of the industry’s welding ability.

The descriptions of how collision repairers have been managing one of the industry’s most fundamental responsibilities suggest training and improved SOPs might be needed immediately. Repairers at the panel and earlier that SEMA Week did offer suggestions for this.

Vehicle Collision Experts CEO Mark Olson, the moderator of the panel and a frequent traveler throughout the industry, kicked off the panel with a troubling anecdote and assessment of industry welding skills.

Olson had been called to evaluate a “fairly new” Toyota Sienna fixed in Henderson, Nev., prior to the customer moving to Washington. After the repair, she drove the vehicle to the Seattle area to join her husband at their new home.

A dash light was on, and the seatbelt didn’t work “exactly right,” so she took the vehicle to a dealership. The dealer sent her to a preferred shop, which realized the vehicle had problems but didn’t want to get involved. It suggested calling Vehicle Collision Experts.

Olson said he told the Henderson shop owner: “‘You probably should buy the car,'” but the shop wanted a chance to fix the vehicle. The shop — certified for some OEMs though not Toyota — arranged for the vehicle to be shipped back to Nevada and for a meeting with Olson while he was in town for SEMA.

Olson visited the shop the morning of the panel, and he asked if the owner wanted to buy the car, but the owner declared nothing was wrong with the Sienna, and his “‘best technician'” had looked at the car.

Olson said he found a bunch of strange “really small” welds with a kind of “triangular look” holding the uniside onto the vehicle. No backside welds were visible — the welds were all single-sided throughout the uniside.

Olson looked at the vehicle’s spot welder, which was missing arms and tips.

“‘We don’t use those,'” the technician explained.

“You can’t make this up,” Olson told the audience.

It was a one-sided spot weld because “‘it’s a smart welder,'” the technician said.

This wasn’t an isolated incident, according to Olson. This was a “collision repair industry story,” he said.

VECO visits hundreds of shops across the country, and “this is really real,” he said.

The shop owner wound up buying the Sienna.

Catching this probably saved the lives of the vehicle occupants, Olson said he remarked after the visit.

The technology at SEMA was cool, but “we gotta get back to the basics,” Olson said.

Welding was a “life and death” matter, he said.

Passing the tests

Panelists included Audi collision instructor and curriculum designer Shawn Hart and I-CAR industry technical support manager Steve Marks, who also handles the Jaguar Land Rover certification program. Both OEMs demand technicians attend welding training and pass a welding exam before they’ll certify an auto body shop.

Olson asked the two men how many of the techs could pass the test at the start of training. Marks estimated 30 percent. “Maybe — 20 percent,” Hart said.

Olson argued that shops were probably sending their best welders to such training. If only 20-30 percent of those were good enough to pass, that was potentially an industry issue, he argued.

Marks said he was probably the most discouraged about attitudes to spot welding. Technicians sent to the JLR course show interest in the MIG brazing and steel welding elements, but not in spot welding, he said. The presumption is that a technician merely has to turn on the machine and pull the trigger, he said.

Marks said he felt like there was “nothing further from the truth” and that spot welding didn’t receive enough focus.

Technicians often don’t realize the need for proper cleaning, he said. They might also overlook the nuances of a particular OEM, he suggested.

Marks recalled going to training in the United Kingdom for JLR and he and others there produced spot welds in the 6-6.3 mm range.

But JLR wants welds between 7-8.4 mm wide. If you don’t realize that and adjust the spot welder, the welds will be incorrect, he said.

JLR wants technicians to take measurements and manually adjust the welder until it achieves the specification, according to Marks.

Marks said that after you work with a technician all week, “it’s very difficult for us” when instructors have to fail them. But the weld was the weld. JLR checks over instructors’ work to ensure they’re not passing work of insufficient quality.

“They watch it pretty closely,” Marks said.

“I really feel like the industry should go more toward this kind of a thing,” Marks said. It signifies that for those who pass, “‘This is a professional,'” he said.

You could argue that the technician only got it right on the day of the test, “but at least you know the skill was there,” he said.

Other problems

Marks said one problem he encounters is inadequate eyesight. Often, techs think they can see fine, only to find vision dramatically improve when instructors let them borrow reading glasses.

Another problem is a lack of steadiness, and the instructors tries to coach techs on how to overcome this.

Often, the technicians never had formal training for welding, said Marks. (He also noted that they might not spend much of their day actually welding.)

Some also resist change, Marks said. Instructors will show how to accomplish the weld specifications through a particular technique, and technicians will say they can’t change to the new method, he said.

Repairers also show a lack of understanding about what changing a setting on the welder actually does in terms of output, he said. They also can be unaware that the welding process on one vehicle might be different on another, according to Marks.

Olson pointed out the absurdity of ignorance about correct welding by asking an audience member from Reliable Automotive Equipment how many bolts removed from her vehicle she’d want replaced — and how many she’d want to be returned tight?

Clearly, the answer was all the bolts, in both cases.

Olson then asked how many of the required welds would she want back in, and how many at the correct strength? All of them was the answer again.

Yet some shops might be dialing in their welders not with test welds but on a customer’s car — assuming correct test welds are being done at all.

If you aren’t destructive-testing on every repair and “every single different stackup,” you’re doing a “disservice” to yourself, your shop and your customer, Pro Spot training development manager Ryan Swanson said.

Swanson said the idea of technicians practicing welds on a customer’s cars was one of the “scariest” things he hears and should “absolutely not” be done.

“I hear it all the time,” he said. It’s constantly encountered in the field too.

A technician should know factors like hand position, settings and location before approaching the vehicle, he said.

There’s a “price” for not knowing the correct repair: the vehicle’s incorrect performance in a subsequent collision, Spanesi Americas technical training specialist and OEM liaison Robert Hiser said. It’s a roll of the dice, he said.

“You just don’t want to run a business with that kind of risk cooked into it,” he said. Every day technicians perform improper repairs statistically increases the odds of litigation, he said.

SOPs and checks

Swanson asked the audience if they had welding standard operating procedures which were followed every time. He offered other items owners and managers should check for:

Do technicians actually understand the OEM procedures in front of them? Do they knew how to properly put settings into a welder. Were technicians completing test welds?

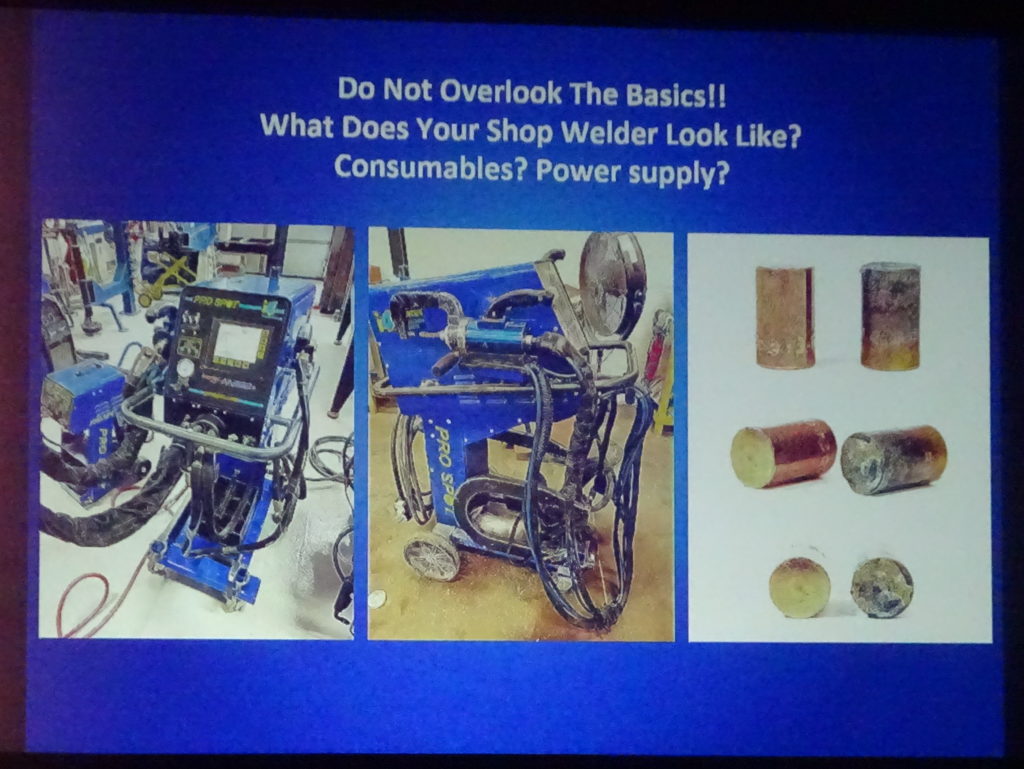

Are tips being changed and dressed (an issue we covered more significantly here)? Does the shop have a maintenance schedule, and who is carrying it out? What does the welder look like? (He gave the example of a welder that looks like a “dinosaur chewed on the arms” and had never been wiped off, compared to a 3.5-year-old one that looked “dang near brand new.”)

Olson suggested owners hand a technician the instructions you want them to read and put a $100 bill 15 pages in there. Often, it’s still there.

At the Collision Industry Conference earlier that week, Technical Committee Co-Chairman Kye Yeung suggested a couple of other shop practices which might improve quality.

Yeung (European Motor Car Works) said his shop mandates removing the wire after welding is complete.

That way, the technician performing the welding “has to start from square one,” according to Yeung. The shop eliminates the risk that the welder assumes whatever wire is in the gun is the right one.

“It makes it easier,” he said.

Yeung’s shop also will on Fridays hold a “weld-off.” All technicians compete to see who has the best weld, and the challenge inspires them to practice their skills during the week.

“It brings everybody up,” he said.

Images:

Vehicle Collision Experts CEO Mark Olson speaks at the SCRS OEM Collision Repair Technology Summit on Nov. 7, 2019. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)

From left, Audi collision instructor and curriculum designer Shawn Hart; I-CAR industry technical support manager Steve Marks, who also handles the Jaguar Land Rover certification program; Vehicle Collision Experts CEO Mark Olson; Reliable Automotive Equipment President Dave Gruskos, Spanesi Americas technical training specialists and OEM liaison Robert Hiser; and Pro Spot training development manager Ryan Swanson participate in the SCRS OEM Collision Repair Technology Summit on Nov. 7, 2019. (John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)

Pro Spot training development manager Ryan Swanson presented this slide of a welder in good and poor condition during the SCRS OEM Collision Repair Technology Summit on Nov. 7, 2019. (Pro Spot slide; photo by John Huetter/Repairer Driven News)